Armenians in Romania History of Armenian Colony

Mass migrations of Armenians were caused by various disasters that frequently affected their motherland. In the 5th century the Byzantine rulers resettled Armenians in Macedonia – this was the beginning of the Armenian Diaspora in the Balkans. The origins of the Armenian community in Romania (and in neighbouring regions) were connected with a particularly gloomy series of events that affected Armenia: the fall of the Bagratuni kingdom in 1045, the conquest of Ani by Seljuk Turks led by Arp Arslan in 1064 (leading to an exodus towards Cilicia, Crimea and Poland), the Tartar invasion of 1239, another Tartar-caused exodus in 1299, the earthquake and famine of 1319, the Mongol invasion in 1342. Subsequent events, such as the Turkish-Persian wars at the beginning of the 17th century, the massacres in 1895 or the genocide in 1915 brought new waves of Armenian refugees to various countries in Europe, one of them being Romania.

The first traces of an Armenian presence in Romania are more than a thousand years old. An inscription on a tombstone in Cetatea Alba is dated 416 according to the Armenian calendar – that is, 967 AD. Another religious inscription dates from 1174. Cilician coins from the 12th century were also discovered in the same city, proving the existence of trade relations between the two regions.

The settlement of Armenians in Moldavia thus took place before the actual foundation of the principality in 1352. Armenians came to Moldavia from the north and east, from Crimea, Galicia and Podolia, regions with significant Armenian population and active Armenian trade centers. The movement of Armenians took place along trade routes – such as the ‘Tartar route’ or the ‘Moldavian route’. Indeed, for a long time, Moldavian trade was dominated by Armenians, and incoming Armenians played a crucial role in the development of Moldavian towns. The early refugees from Armenia belonged the upper classes – aristocrats, merchants, craftsmen – and they used their skills and knowledge of a wide range of Oriental and European languages to develop their trade networks.

The greatest Romanian historian, Nicolae Iorga, stated in Choses d’art arméniennes en Roumanie (1935) (quotation taken from Sergiu Selian – Historical Sketch of the Armenian Community in Romania) that “Since the principality of Moldavia was actually created by way of trade, those who followed this way became participants in the creation of the national state of Moldavia. Therefore Armenians are in a way the parents of Moldavia.”

The formation of Armenian communities in Moldavia may have started as early as the 11th century, but we only have solid documentary evidence from the 14th century. The present Armenian church in Cetatea Alba most probably dates from the beginning of the century. In 1421, a French traveller representing king Henry V of England, Guillebert de Lannoy, noted that the city was inhabited by Italians, Romanians and Armenians: “Et vins à une ville fermée et port sur laditte Mer Maioure, nommée Mancastre ou Bellegard, où il habite Genevois, Wallackes et Hermins…” (Neagu Djuvara). The town had previously been a Genoese trade center – Italian and Armenian merchants were often associates in the regions around the Black Sea. The importance and power of Cetatea Alba is proved by the fact that it was able to issue its own coins and even wage its own local wars. There also was a large Armenian community – with its own church, now lost – in the other Moldavian port, Chilia.

In the northern part of Moldavia, along the ‘Moldavian route’ connecting Chilia and Cetatea Alba with the great city (and Armenian center) of Lemberg/Lwow/Lviv/Lvov, Armenians were among the founders or early settlers of several towns. These Armenians had close connections with their fellow nationals in the neighbouring regions that had recently come under Polish and Lithuanian sovereignty.In 1341, the Armenians in Roman purchased a (wooden) church from the local Saxons. The old church in Botosani was built in 1350; Nicolae Iorga – who was born in Botosani – said that the town would have remained a village without the Armenian contribution to its development. The old church in Iasi – also dedicated to St Mary – was built in 1395 by the priest Hagop and the haji Markar. The epigraph is actually the earliest ‘document’ connected with the city. The town of Siret, the capital of Moldavia in the 1370s, had two Armenian churches that disappeared in the Middle Ages. The following capital, Suceava (1390 – 1564) became the main center of Armenians in Moldavia. It already had an Armenian church in 1389.

In the northern part of Moldavia, along the ‘Moldavian route’ connecting Chilia and Cetatea Alba with the great city (and Armenian center) of Lemberg/Lwow/Lviv/Lvov, Armenians were among the founders or early settlers of several towns. These Armenians had close connections with their fellow nationals in the neighbouring regions that had recently come under Polish and Lithuanian sovereignty.

In 1341, the Armenians in Roman purchased a (wooden) church from the local Saxons. The old church in Botosani was built in 1350; Nicolae Iorga – who was born in Botosani – said that the town would have remained a village without the Armenian contribution to its development. The old church in Iasi – also dedicated to St Mary – was built in 1395 by the priest Hagop and the haji Markar. The epigraph is actually the earliest ‘document’ connected with the city. The town of Siret, the capital of Moldavia in the 1370s, had two Armenian churches that disappeared in the Middle Ages. The following capital, Suceava (1390 – 1564) became the main center of Armenians in Moldavia. It already had an Armenian church in 1389.

In 1365, the Armenian churches in Moldavia were included in the jurisdiction of the Armenian bishopric of Lemberg, established in 1363. This comes to confirm the venerable age of several Armenian churches in the principality. This in turn proves the existence of large and prosperous Armenian communities in Moldavian towns from a very early period.

The reign of Alexander the Good (1400-1432) witnessed an increase in the Armenian population in Moldavia. On 30 July 1401 Alexander appointed Ohanes as the bishop of Armenians in Moldavia. (This was several months before the final establishment of the Romanian Orthodox hierarchy!) In a charter dated 8 October 1407, prince Alexander invited Armenian merchants from Poland to settle in Moldavia, granting them exemptions of taxes and customs duties. 700 Armenian families settled in Suceava, while others settled in Siret and Cernauti (the latter was only a village when Armenians arrived; the Armenians were the actual founders of the town).

3,000 more Armenian families came in 1418 and settled in seven Moldavian towns: Suceava, Hotin, Botosani, Vaslui, Galati, Iasi, Dorohoi. Following the Polish model, Armenians were given special privileges. One of them were the tax reductions and tax exemptions mentioned above. Conflicts between Armenians were tried by Armenian judges (following the code of Mkhitar Gosh), and conflicts between Armenians and non-Armenians could only be tried by the prince and his council. Land owned by Armenians was given special protection against any encroachments.

About 10000 Armenians settled in Moldavia during the reign of Stephen the Great (1457 – 1504). In 1475, after the Turkish conquest of Caffa, Stephen offered asylum to Armenian refugees and settled them in Suceava, Iasi, Botosani, Roman and Focsani. Just like his predecessors, he also gave special privileges to Armenian merchants from Lemberg. It also seems that Stephen had special units of Armenian cavalry in his army. The prosperous state of the Moldavian economy during Stephen’s reign stimulated the development of Armenian communities. The main Moldavian export was cattle – and the cattle trade was an Armenian quasi-monopoly. Armenians bought – and later even bred – cattle in Moldavia and sold it in Poland and Germany. They also exported wheat, wax, sheep, horses, hides and brought spices, lace, weapons from the East and Western Europe. Armenians had their own guilds and were involved in the administration of Moldavian towns.

In 1484, the Turks conquered the ports of Cetatea Alba and Chilia and Stephen was unable to take them back. Armenians in Cetatea Alba were deported to Constantinople. The Black Sea became a ‘Turkish lake’ and Armenian trade was partly blocked. However, trade between Moldavia and Central and Northern Europe went on – and Armenians played a major role in it. Further disruption was brought by the Polish invasion in northern Moldavia and by subsequent Moldavian retaliation towards the end of Stephen’s reign. Armenians from Suceava fled to Transylvania and Galicia.

The life of Armenian communities continued largely unchanged during the first half of the 16th century. Armenians continued to enjoy significant wealth and political security. The Armenian Petru Vartic, Peter Rares’s translator, became the commander of the Moldavian army and the fortress of Suceava. Petru Vartic’s son, Iurasco Varticovici, was the postelnic (chamberlain) of prince Iancu the Saxon. The monastery of Hagigadar, near Suceava, was built in 1512, during the reign of Bogdan III, Stephen’s son.

The life of Armenian communities continued largely unchanged during the first half of the 16th century. Armenians continued to enjoy significant wealth and political security. The Armenian Petru Vartic, Peter Rares’s translator, became the commander of the Moldavian army and the fortress of Suceava. Petru Vartic’s son, Iurasco Varticovici, was the postelnic (chamberlain) of prince Iancu the Saxon. The monastery of Hagigadar, near Suceava, was built in 1512, during the reign of Bogdan III, Stephen’s son.

In 1538, during the reign of Peter Rares, a great Turkish invasion led to the destruction of a large part of Suceava. More than a decade later, Peter’s son and heir, Ilias, decided to convert to Islam. In order to restore faith in his family and prove his ‘Orthodoxy’, Ilias’s brother, the new prince Stephen Rares, tried to forcibly convert Armenians by a decree issued on 16 August 1551. Armenian churches in Hotin, Siret, Iasi, Vaslui, Botosani, Roman, Suceava were destroyed or damaged. Stephen was assassinated a year later by Moldavian noblemen tired of his cruelty, greed and immorality. Persecutions ceased and Armenian churches were repaired.

A new wave of persecutions occurred during the nine-month reign of Stephen Tomsa (1563), when Armenians were accused of having supported the deposed prince Despot. Things came back to normal after Stephen’s assassination. During the following century, however, Armenians decided to keep a low profile in the all-too-dangerous world of Moldavian politics.

In 1572, John, the son of the Armenian Serpega, became prince of Moldavia. An enemy of the higher nobility and popular with the peasants, John fought valiantly against the Turks but was betrayed by a group of noblemen and executed in 1574. During the following period of political instability, two of John’s half-brothers, Garabet Ioan Potcoava and Alexander Serpega, briefly captured the Moldavian throne in 1577 and 1578. The first is the main character in Mihail Sadoveanu’s novel Nicoara Potcoava. Alexander’s son, Petru Cazacul (Peter the Cossack), also reigned for a few months in 1592. His main advisor was the Armenian Ovac Matisovici. Two other members of the Serpega family, Constantin and Lazar, unsuccessfully claimed the throne in 1578 and 1591.

Armenians also settled in Transylvania from a very early period – perhaps even the 11th century. Migrating Hungarians brought two groups of Armenians into Pannonia, and some of them may have got to Transylvania. Hungarian chroniclers also mention that Armenians were among the various nations colonized by Duke Geza and King Stephen (“Bohemi, Poloni, Graeci, Hispani, Hismaelitae, Bessi, Armeni etc.”). Other Armenians may have come from Poland and the Balkans. During the reigns of Andras II and Bela IV Armenians had their own monasteries and estates in Transylvania (Monasterium Armenorum, Terra Armenorum). In 1243, king Bela IV confirms their privileges. In 1281, king Ladislas IV donates Armenian properties to the Augustine friars – probably as a result of the decrease in the number of Armenians. In 1343 we have mention of “Martinus episcopus Armenorum de Tolmachy”. In 1399 Armenians are listed among the non-Catholic inhabitants of Brasov, together with Greeks, Romanians and Bulgarians. There was an Armenian priest in Sibiu in 1447. Armenians are also mentioned in Bistrita in the 16th century. Thus there was a continual Armenian presence in Transylvania, although a strong and stable community was only established during the 17th century.

Armenians came to Wallachia at a later date, perhaps towards the end of the 14th century. Between 1400 and 1435 we have mentions of Armenian communities in Bucharest, Targoviste, Pitesti, Craiova and Giurgiu. The fall of Constantinople in 1453, the conquest of Crimea in 1475 and other events led to the increase of the number of Armenians in the area. There used to be an Armenian church in the old Wallachian capital of Targoviste, an in 1581 an Armenian church was built in Bucharest. Prince Michael the Brave (1593 – 1601) had the Armenian Peter Grigorovici as his main ambassador. Peter’s brother, Joseph, was an envoy of the Austrian emperor in Persia in 1609.

The wars between Turkey and Persia at the beginning of the 17th century led to a massive emigration of Armenian population. Armenian communities in Romania were ‘rejuvenated’ as a result of this exodus. Later on Armenians opposed to the Uniation also came to Moldavia from Poland. In Moldavia, new churches were built in Suceava (St Simon), Botosani (Holy Trinity), Iasi (St Gregory the Enlightener), Galati. The old churches in Iasi and Roman got their present form during this century. Catholic and Apostolic Armenians built the church of Baratia in Bucharest in 1629. More Armenians would come to Wallachia from Bulgaria in the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries.

Thus ever since the 14th century Armenians were an important element in the life of the Romanian principalities. Above all in Moldavia, Armenians played a crucial part in the development of trade, crafts and urban life. They had their own guilds, their own courts, their schools, even their own mayors. And, in good Armenian tradition, they built an impressive number of churches. Armenians shared the ups and downs of the agitated history of the area, and came to be regarded among the country’s ‘founding fathers’. At the same time, unfortunate events affecting Armenia and other regions inhabited by Armenians sent wave after wave of Armenians to the area, bringing ‘fresh blood’ to the old communities. At the beginning of the 18th century, the prince and scholar Demetrius Cantemir, author of the classic Descriptio Moldaviae (The Description of Moldavia) listed Armenians first in his list of non-Romanian inhabitants of the principality. Armenian churches, he says, are just as large and decorated as those of Romanians, and Armenians enjoy full religious freedom.

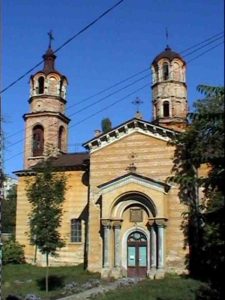

The initial Armenian church in Botosani – dedicated to St Mary – was built, as we have already seen, in 1350. The position of the church and the ‘Armenian Quarter’ of the town – in the very heart of Botosani – prove the venerable age of the Armenian community. Armenians played a major part in the development of the town. Indeed, the town had two ‘mayors’ (soltuz, Schultheiss) – one of the Romanian, the other Armenian. Armenians were also represented in the city council – half of it at the beginning, then a share equivalent to their share in the overall population of the town. Armenians also had their own guilds and were actively involved in the economic, social and cultural life of the place.The main church was repaired after the damages of 1551 (the main elements of the present building seem to date from the 16th century); an exonarthex was added in 1783, and a sacristy was added during the renovation of 1826. The bell tower built in 1816 was also used as an observation point by the city guards.

The second Armenian church in Botosani – dedicated to the Trinity – was built in 1717, close to the main church of St Mary. It replaced a wooden church dedicated to St Oxen (Auxentius), built in 1560. It was also extended in 1832. A chapel dedicated to the Annunciation was built by Ana Toros (who dedicated it to the memory of her husband, Avedik von Pruncul) in the Armenian graveyard. The graveyard in Botosani, like its counterparts in Suceava and Iasi, has a very valuable collection of old monuments.

The Armenian church in Iasi – also dedicated to St Mary/ Sourp Asdvadzadzin – was built in 1395, close to the ‘Old Street’ (Podul Vechi) – the town’s main commercial street. It was damaged in 1551 and rebuilt or repaired many times. Its overall style dates from the 17th century. It was at the beginning of this century that the church was used for about 20 years (1607 – 1624) as a residence of Armenian bishops in Moldavia (later on they moved back to Suceava). The last thorough renovation dates from 1803. A second Armenian church, dedicated to St Gregory the Enlightener, was built in 1616 in Shoemakers’ Street (Ulita Cizmariei) and extended in the 18th century. It was destroyed in the great fire of 1827 and the ruins were finally demolished in 1899. A chapel in the new Armenian graveyard was built in 1881. An Armenian school existed in 1646; it was reopened in 1803.

A separate Armenian guild is mentioned in Iasi. Armenians also dominated or formed a significant part of other guilds: the blanket makers’ guild, the shoemakers’ guild, the goldsmiths’ guild. There were also Armenian bankers and innkeepers – such as the owners of the famous Missir inn.

The main center of Armenians in Moldavia was Suceava. It already had an Armenian church in 1388 and during the following centuries Armenians built at least seven churches in the town (twelve, according to some researchers). Four of them still exist. Since 1401, Suceava was the residence of the Armenian bishops. In 1506, bishop Simon became the first autonomous bishop. The see remained vacant starting from 1691. During 1790-1808, 1826-1839, 1841-1843, 1849-1920, the Armenian Patriarchy of Constantinople sent clerics to act as chiefs of the diocese.

The monastery of St Oxen is first mentioned in 1415 as the residence of the bishop Avedik. The main church (dedicated to St Oxen) was rebuilt (and painted – parts of the fresco can still be seen today) around the middle of the 16th century, and perhaps renovated in 1606 by a rich Armenian called Agopsa, who is buried inside the church. The belltower with the chapel of St Gregory the Enlightener was built in 1606 by Krikor who, according to the tradition, may have been Agopsa’s brother. The neighbouring house with the chapel of St Mary dates perhaps from the 15th century. The monastery was the main residence of the Armenian bishops in Moldavia. It also had its own school and its carpet manufacture. During the war of 1690-1691, the Polish army of king Jan Sobieski occupied the monastery and stengthened its walls. It was perhaps at this time that it got the name of Zamca (locals still call it the ‘Armenian fortress’). In 1809 the monastery was taken over by the Austrian state and used as an ammunition store. The Armenian community got it back – after lengthy trials – in 1829.

The second Armenian monastery in Suceava, Hagigadar, was built in 1512 by the brothers Dragan and Bogdan Donavachian, two local Armenian merchants, after a vision of St Mary. The church, perched on a small hill outside the town, soon became famous for its reputed miraculous powers and is still a popular place for pilgrimage. It is built in the Moldavian style of early 16th century. It has a bell unearthed in the old Armenian graveyard which – according to its inscription – was made in 1244 for the monastery of Tatev in Armenia. Inside the church there are altars donated by the Goilav and Capri families in the 18th century. The painting dates from the late 19th century.

The church of St Simon was built by an Armenian called Donig in 1513 and renovated in 1606 by a certain Simon. Its courtyard is actually the old Armenians graveyard. The church is also called the Red Tower (Turnu Rosu) because of its 17th century red brick tower.The church of the Holy Cross – today the main Armenian parish church in Suceava – was built in 1521 by Cristea Hanco on the place of an older church mentioned around 1504. In 1776 the church was added a chapel dedicated to St John the Baptist, the donation of Mariam and Hovhannes Capri. In the new graveyard baron Varteres von Pruncul built in 1902 a chapel in traditional Armenian style.

The other Armenian churches of Suceava disappeared at various times in the past. The church of St Mary existed before 1512 close to the church of the Holy Cross. The church of the Holy Trinity was demolished at the end of the 18th century; its remains were used to build the porch of the church of the Holy Cross. The church of St Nicholas is mentioned in 1830.

Suceava was an important trading center, and for a long time was also the capital of Moldavia. Even after the capital was moved to Iasi in 1564 Suceava kept its central place in the Armenian community in Moldavia. Armenians remained loyal to the town even during the period of the town’s decay in the 18th and 19th centuries. Old documents repeatedly mention Armenians making up around 20% of the town’s population. The heart of the Armenian community was around the churches of Holy Cross, St Simon and Zamca. Just like Botosani, and perhaps like Roman, Suceava also had two mayors – one of them Armenian.

Siret – the old Moldavian capital – had two Armenian churches in 1507; they were damaged in 1551 and have since disappeared. The Armenian church in Gura Humorului was built in 1849 and given to the Romanian Orthodox church in 1934, due to the lack of Armenians in the area.

The first Armenians came to Cernauti in 1418 and transformed the village into a small commercial town. They were given special privileges by Stephen Tomsa II in 1614. In 1740, when the two Armenian churches were destroyed by fire, Armenians formed half of the town’s population.Armenians were among the first inhabitants of the town of Roman, established in the 14th century. In 1355, local Armenians purchased a wooden church built in 1341 by the local Saxons.

The church – or perhaps one of its successors – was damaged in 1551. The stone church dedicated to St Mary was built in 1609 by Agopsa. It was renovated towards the end of the 17th century and again in 1864 by Teodoros Soghomonian and Doing Simeon Pipian (the latter was the first Armenian in the Romanian parliament). The style of the church is similar to that of the church in Iasi. Roman has traditionally been an important economic and cultural center for Armenians in Moldavia.

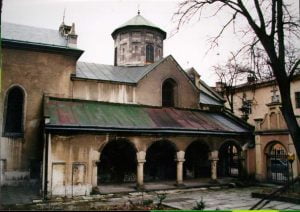

The church in Cetatea Alba was built perhaps in the early 14th century. Foreign travellers mention it in the 15th century, sometimes as the residence of Armenian bishops. Its small size, its simple stile as well as the position of its floor – below the current ground level – suggest that the current building is quite old. After the Turkish conquest, local Armenians were deported to Constantinople, but throughout the period of Ottoman rule the town had an Armenian community.

The town of Chilia had an Armenian community at the beginning of the Middle Ages. In 1768 the German geographer Kleeman mentions two Armenian churches in Chilia (they no longer exist).

Armenians were colonized in Vaslui in the 15th century. Armenian churches are mentioned in 1526 and 1608. Both the Armenian community and the Armenian church disappeared in the Middle Ages.

The Armenian church in Hotin was built in 1480. It was destroyed in 1551 and rebuilt in 1645. The town and the fortress were occupied by the Turks in 1713 and the Armenian community disappeared.

The town of Ismail, on the Danube, had an Armenian church dedicated to St Mary in 1669. The same writer, Luigi Maria Pidou, mentions an Armenian church in Tighina. Both (fortified) towns were under Turkish rule at the time.

Soroca also had an Armenian church in the 17th century. In 1787 Charles de Peysonnel mentions an Armenian church in Causani.

Several Armenian churches were also built in Targu-Ocna. The church of St Mary was built in 1825, replacing an 18th century wooden church. There was another chapel in 1600. The church of St Nicholas was built in 1580, was rebuilt in 1775 and was given to the local Romanians in 1845. At the beginning of the 13th century there also was a wooden Armenian church in Targu Trotus., which was replaced in 1333 by a wooden one; only its ruins survive today. In the nearby village of Caiuti there used to be an Armenian catholic church.

In Galati there was a wooden Armenian church in 1669; the town also had an Armenian bishop at the time. The church was burned by the Turks in 1821 and rebuilt a year later. The current church – dedicated to St Mary – was built in 1858. The Armenian community in the town increased during the 17th century, during the 19th century – when the town developed as a result of its status of a free port – and again after the genocide of 1915. The St Mary church in Braila was built in 1837.

The Armenian community in Focsani is also one of the more recent ones. On the Wallachian side, the church of St George was built between 1700 and 1715. On the Moldavian side, the church of St Mary was built in 1780; it has old and interesting tombstones. The chapel in the graveyard, dedicated to the Resurrection and built in 1891, is the donation of the brothers Harutiun and Garabet Popovici. There also used to be Armenian churches in Barlad, Cotnari, Dorohoi, Husi, Tecuci, Negostina (near Suceava; the church of St Nicholas, built in 1862).

The first Armenian communities in Wallachia are mentioned at the beginning of the 15th century. There may have been an Armenian church in the old capital of Targoviste. We know that a church was built there in 1740 and was later destroyed.

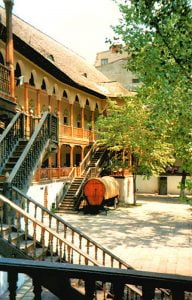

In 1581 there was an Armenian church in Bucharest. In 1629 Catholic and Apostolic Armenians built the church of Baratia (Brotherhood) close to the center of the town, in the Armenian Quarter. Baratia became an exclusively Catholic church in 1638 and the Apostolic Armenians built their own wooden church on the edge of the city, in what was to become known as the Armenian Street (first mentioned in 1772). This church was replaced by another one made of stone in 1685 by Hagi Hariton Amira Hoveantz. The church burned in 1781 and was rebuilt the following year. It is quite likely that there was more then one (Apostolic) Armenian church in Bucharest; we have mentions of a second church at the beginning of the 19th century. The existence of an Armenian guild in Bucharest is confirmed by charters issued by princes Alexander Ipsilanti (1775) and Michael Sutu (1791). The list of Wallachian guilds in 1820 also includes the Armenian guild. In 1821 there were 187 Romanian registered masters in Bucharest – and 37 Armenian ones. The leader of the bakers’ guild was the famous Armenian Babik. There also were several famous Armenian-owned inns in Bucharest: Manuc’s Inn, one of the main landmarks of the city, the Campineanu Inn, owned by brothers Petre and Ioan Serafim (1832 – 1846), Slaison the Armenian’s Inn (beginning of the 19th century), Simon’s Inn (1870 – 1889), Grigore Caracas’s Inn (1870 – 1880).

The Armenian church in Pitesti was built in 1693, rebuilt in 1852 and renovated in 1882. It is dedicated to St John the Baptist. There also were Armenian communities in Craiova, Giurgiu, Ramnicu Valcea, Curtea de Arges, Turnu Severin, Buzau, Ploiesti, but they did not have their own churches.

In the province of Dobrogea/Dobrudja (under Turkish rule since 1420) there also were Armenian communities and churches. There was an Armenian community in Babadag around 1500, and a church is mentioned in 1649. In 1803 there were 40 Armenian houses in Babadag, and a church dedicated to the Holy Cross, which burned in 1823, was rebuilt in 1829, burned again in 1891 and rebuilt in 1896 as the Church of St Mary. The church was destroyed by the earthquake of 1940. Around the middle of the 18th century an Armenian church was built in Sulina; it was destroyed by bombs during the second world war. In Constanta there was an Armenian church prior to 1760 – as well as an old Armenian graveyard. About a fifth of the houses in the (then very small) town of Constanta in 1878 (when the region returned to Romanian administration) were Armenian. In southern Dobrogea there were Armenian communities, churches and schools in Silistra and Bazargic/Dobric.

Most Armenian churches in Romania are in local rather than Armenian style. At the same time, however, Armenian architecture and decorative arts enjoyed considerable influence in Romania. A French author claimed in the 19th century that from an architectural point of view the region of the Lower Danube was an Armenian colony. This assertion is obviously exaggerated, but it is not entirely unfounded. There are many Romanian churches where the Armenian influence is obvious. The churches of Dealu, Dragomirna, Curtea de Arges of the church of the Three Hierarchs are obvious examples. Quite interestingly, the famous legend of the difficult and tragic building of Curtea de Arges monastery has an Armenian counterpart – the legend of the Ashtarak bridge:

Armenian version: The bridge collapses every time its foundations are built. The old men in the village are advised to sacrifice an orphan to the river. A young girl is brought by her stepmother and closed in the foundation. When the wall reaches her knees, the girl sings:

They walled, dear mother, they walled,

Up to my knee they stoned…

Then she sings:

They walled, dear mother, they walled,

Up to my breast they stoned…

(…) They walled, dear mother, they walled,

Up to my throat they stoned…

After that, her voice is no longer heard and the foundations stay firm. Similar legends are associated with the bridges of Batman and Koter.

Romanian version: The Black Prince hires Manole and nine other master craftsmen to build a church more beautiful than any other in the land. They start building, but what is built during the day collapses during the night. Manole has a strange dream and the builders decide to close in the walls the first woman, mother, wife or sister that comes to bring them food in the morning. The first to come is Manole’s wife, Ana. Manole, maddened by grief, tells his wife this is only a game and she is gradually incorporated in the walls:

The wall rose

And surrounded her,

Up to her ankles,

Up to her thighs.

And she, poor her,

Laughed no more,

And kept saying:

Manole, Manole,

Master Manole,

Stop this joke,

It is no good.

Manole, Manole,

Master Manole

The wall is crushing me,

It is breaking my body!

Manole kept silent,

And he kept building.

The wall was rising

And enclosing her

(…) Up to her ankles,

Up to her thighs,

Up to her ribs,

Up to her breast,

Up to her lips,

Up to her eyes.

The church is finally completed and is the most magnificent in the country. The prince orders the scaffoldings to be removed and the builders are left on the roof, to prevent them from building anything more beautiful. The masters make themselves wings and jump from the roof. When jumping, Manole hears the faint voice of his wife, collapses from the roof and dies.

It is interesting to note that Nicolae Iorga claimed that the architecture of the church in Curtea de Arges is due to Armenians coming from the town of Argesh near Lake Van. A similar legend is associated with the church of the Three Hierarchs in Iasi – a church with obvious Armenian influence in its architecture and exterior decorations.

The relatively peaceful reign of Vasile Lupu (1634 – 1653) was a period of prosperity for Armenians in Moldavia. In 1646 we have a mention of Armenian schools in Iasi (capital of Moldavia since 1564). This came to an end in 1650, however, because of a massive Cossack invasion. The end of Vasile Lupu’s reign was marked by fighting and repeated invasions.

In 1671, Armenians were among the supporters of the rebellion led by the Hancu brothers against the tyranny and excessive taxes of prince George (Gheorghe) Duca. The rebels were defeated (with Turkish help) in the battle of Chisinau and their leaders were forced into exile. According to some authors, the Hancu brothers themselves were of Armenian origin.

In 1672 there was a massive Turkish invasion into Moldavia and during the following years Moldavia (and to some extent Wallachia) became a battleground in the wars between Poland and the Ottoman Empire – with truly devastating effects for the principality. Fighting resumed in 1683, when the Armenian monastery of Zamca was turned into a fortress by the army of the Polish king Jan Sobieski. These unfortunate events led to a large part of the Armenians in Moldavia leaving their homes and taking refuge in Transylvania.

The movement of Armenians across the Carpathians had started earlier – around the middle of the century. In 1654, a group of Moldavian Armenians led by Mardiros Gandra and the Azbey brothers went to Transylvania but – because of political troubles – they were forced to move back and settled in Gheorgheni/Gyergyoszentmiklos. A manuscript copied in 1647 in Targu-Mures (Marosvasarhely) proves the existence of Armenians in the town.

In 1672, 3000 Armenians from Moldavia, led by their bishop, Minas Zilihtar, fled to Transylvania. At the beginning the migration was thought to be temporary, but eventually Armenians had to settle west of the Carpathians. Prince Michael Apafi (Apafi Mihaly) allowed Armenians to settle in Bistrita, Gheorgheni, Miercurea-Ciuc, Petelea, Sumuleu, Alba-Iulia. A Charter issued by Apafi in 1680 gave Armenians autonomy, the right to exercise freely their trade and crafts and to elect their own judges. An important Armenian community settled initially in Bistrita, where they built a church. Conflicts with the local Saxons (who were afraid of Armenians competition) forced Armenians to leave the town and find other places to settle.

Some of the Armenians who had taken refuge in Poland moved to Transylvania in order to avoid conversion to Catholicism. It soon became apparent that – despite Michael Apafi’s protection – they would still have to convert even in the principality (which became part of the Habsburg empire in 1699). The organizer of the new Armenian Catholic community was Oxendius Varzarescu/Varzarian, an Armenian from Botosani who had been educated in Rome between 1670 and 1684. Varzarescu convinced bishop Minas to be converted to Catholicism by the bishop of Lemberg, Vartan Hunanian. After Minas’s death in 1686, Varzarescu became the next Armenian Catholic bishop in Transylvania. In 1669, John Kieremowicz became the nominal Armenian Catholic bishop of Suceava, but local Armenians elected their own Apostolic bishop, Sahak. Varzarescu’s first see was Gheorgheni, then he moved to Bistrita. Since the Roman Catholic see in Transylvania had been vacant since 1566, Varzarescu was also its leader until his death in 1715.

After Oxendius Varzarescu’s death, pressures from the Latin-rite church, particularly the Jesuits, and divisions among Armenians in Armenopolis and Elisabethopolis prevented the election of another Armenian Catholic bishop.

In 1700, Varzarescu and the Transylvanian Armenians were awarded by the Austrian emperor Leopold (in exchange of 25,000 florins) the right to build their own town on the Somes river, near the Martinuzzi castle and a small Romanian village. The first inhabitants were 70 Armenian families coming from Bistrita. The town – to be known as Armenopolis (the official name), Armenierstadt (in German), Szamosujvar (in Hungarian) or Gherla (in Romanian) – was the first in the Austrian empire to be built according to a general plan, designed by the architect Alexanian from Rome. There were four perpendicular main streets and the architecture and position of the houses, as well as their prices and their owners’ social status were carefully regulated. 3000 Armenian families settled in the Armenopolis and for quite a long time the town’s population was almost exclusively Armenian.

The other main Armenian center in Transylvania was Elisabethopolis (Erzsebetvaros, Ebesfalva, Ibasfalau, Dumbraveni), a former estate of the Apafi family, where Armenians had already settled by 1658. The place had previously been inhabited by Romanian serfs and Hungarians; there also was a Saxon community. Armenians also settled in Gheorgheni, Frumoasa (Csikszepviz), Ditrau (Ditro) – all of them having Armenian churches –, Cluj, Sibiu, Brasov, Oradea, Arad, Aiud, Bistrita, Alba Iulia, Reghin, Abrud, Nasaud, Odorhei, Sfantu Gheorghe, Targu Secuiesc, Deva, Carei, Joseni, Remetea, Lazarea, Toplita, Suseni, Gurghiu.

Armenians had brought from Moldavia the tradition of their own institutions. They were given special privileges in Transylvania and enjoyed a large degree of autonomy. Armenians had their own courts, led by their mayors, which followed the code of Mkhitar Gosh. By imperial decree, it was forbidden to any stranger to enter Armenian towns without a written pass issued by the mayor or the city council. An Armenian Company was founded in order to connect the various Armenian communities, in particular those in Armenopolis and Elisabethopolis. Since 1689, the Company had its own judex helped by three assistants. They had to look after of tax collection and the execution of princely decrees. Later on these powers were transferred to the municipality of Elisabethopolis, which was in charge of all Armenians in Transylvania outside Armenopolis. The municipalities of Gheorgheni and Frumoasa – subordinated to that of Elisabethopolis/Dumbraveni – were led by mayors (biro). The powers of these mayors were gradually reduced and in 1757 the system was replaced by the hundreds, with their leaders acting as intermediaries between the municipality and ordinary citizens.

The Armenians that had settled in Frumoasa in 1675 built a church in 1700. It is the oldest surviving Armenian Catholic church in Romania. In Gheorgheni, Armenians came in 1672 and built the church of St Mary in 1733 (a bell tower was added in 1734).

In Armenopolis, Armenians built a wooden church in 1675, before the actual foundation of the town. Several other churches were built during the following centuries. The church of the Annunciation (the Solomon church) was built in 1724. The Trinity Cathedral was built between 1748 and 1776. Between 1885 and 1894 a chapel dedicated to St Gregory the Enlightener was built beside the Armenian orphanage. Another chapel was built in the graveyard. A school had been opened as early as 1670 and several other schools would be organized over the next two centuries.

In Elisabethopol, the church of the Holy Trinity was built in 1723, to replace an older, wooden church. The St Peter and Paul church was built in 1796 by the Mkhitarian friars. The Armenian church of St John the Baptist was given to the Lutheran community in 1920. The cathedral of St Elizabeth was built in 1850. The first school was built in 1685; a school for girls was inaugurated in 1746. The Mkhitarian friars from Venice inaugurated a school where Armenian, Hungarian, German and Latin were taught. Armenian schools were also organized in Oradea (1749), Frumoasa (1797), Gheorgheni (1832) and Cluj.

Throughout the 18th century, Armenians in Transylvania played a major role in the development of the local economy. Using their traditional networks and skills, They acted as intermediaries between the East and Western Europe. In their main towns, Armenians had their own guilds. They were locksmiths, furriers, silversmiths and goldsmiths, carpet makers, brewers, lace makers. The guilds also were involved in building churches and schools and caring for the poor. Armenians also organized some of the first manufactures in Transylvania – one producing leather, in Armenopolis (a tradition that remained famous well into the 20th century), and another producing candles, in Elisabethopolis. Armenopolis and Elisabethopolis were declared ‘free royal cities’ in 1726 and 1733, respectively.

The 18th century was not a very good one for Armenians in Moldavia and Wallachia. The economic hardship generated by extremely high taxes and frequent wars were compounded by the preference of Phanariote princes for Greek traders. Some trade restrictions forced Armenians to extend their activities as money lenders. Armenians were also not admitted to the Academies in Iasi and Bucharest (where Theology was one of the main subjects). In order to protect themselves in extremely volatile political circumstances, some Armenians tried to get additional guarantees by adopting Russian or Austrian citizenship. Still, princes tried to preserve the privileges previously granted to Armenians. For instance, Constantin Mavrocordat, in 1742, and Alexandru Mavrocordat, in 1784, issued charters containing tax reductions and rules aimed at protecting Armenian merchants (for instance against excessive fees for cattle grazing). In 1737, Grigore Ghica warned his representative in Cernauti against persecuting Armenian merchants coming from Poland.

In 1775, Austrians occupied the north-western corner of Moldavia, including the towns of Suceava, Cernauti and Siret, which they named Bukowina (Bucovina in Romanian). There were about 2,000 Armenians in the area, about 2% of the total population. They were thus to some extent separated from the rest of Armenians in Moldavia, but family and economic ties continued and Romanian was kept as the second language. The Armenian language and the Apostolic denomination were carefully preserved. A few Galician, Catholic and Polish-speaking Armenians came to Bucovina under the Austrian rule. The Armenian Catholic Church in Cernauti was built between 1870 and 1875 (today it is used as a concert hall).

Although they were not Catholic, Armenians in Bucovina were to some extent favoured by the Austrians, who did not like Jewish merchants. Emperor Joseph II decreed that administrators must ‘abandon all further investigations about their religion, and leave them alone in their business and their way of life; one must seek to bring hither more people like them.’ (quotation from E. C. Suttner – ‘Armenians and Other Religious Minorities in the Habsburg Empire’). In 1786, Suceava was declared a free commercial town. Besides the ‘right of public worship’, the Armenian parish in Suceava had the right to keep registers that were recognized by the state. The churches, chapels, school, two priests and teachers preserved their former functions. In 1802 there were 205 Armenian families in Suceava, with 965 members. In 1820 there were 200 Armenian houses in Suceava. In 1825 there were 250 families, 530 in 1857 and 300 (1200 persons) in 1890. There were 30 Armenian houses in Cernauti and 10 Armenian houses in Siret. In 1909, there were 57 Armenian families in Cernauti, 15 families in Gura Humorului, 6 families in Radauti and two in Vatra Dornei.

About one quarter of Armenians in Bucovina were landowners, owning according to an estimate as much as one third of the land in the region. The main landowner families were Capri, Prunculian, Aritonovici, Asachievici, Bogdanovici, Stefanovici, Aivas, Zaharasievici, Zadurovici. The archaeological collection of the baron von Kapri in Iacobesti and the library of Popovici family in Vatra Dornei are proofs of the intellectual quality of these families. The activity of Armenian traders lost some of its importance due to the new, stricter borders, restrictions on trade and Jewish competition. Armenian craftsmen produced soap, candles, foods and spirits, leather objects, medicine and jewels.

The Armenian community in Bucovina was granted a special statute that preserved its autonomy. It had a Great Assembly of 12 members that sat every year and a Trust Council of 7 members. Since the see in Suceava was vacant, the Patriarchy in Constantinople was in charge of the local Armenians. A new statute adopted in 1872 granted membership of the officially recognized parish in Suceava to Armenians outside Bucovina, a measure aimed at easing the practice of the traditional Armenian trade. The Armenian General Benevolent Union was also represented in Cernauti. The Armenian school in Suceava was opened in 1824 in which ‘apart from the usual subjects in primary schools in the Armenian language, there [is to be] also a teacher to give instruction in the German and Romanian languages and Armenian Church music is also to be cultivated.’ (quotation from E. C. Suttner – ‘Armenians and Other Religious Minorities in the Habsburg Empire’). In 1879 the Catholic ‘Isahakian’School was opened in Cernauti. It was aimed at orphans from from Bucovina, Bessarabia and Galicia.

Many of the Armenians in Bucovina were rich and cultivated. Some of them – such as the members of the Capri and Pruncul families – became Austrian nobles. The first mayor of Cernauti, Petrovici, was Armenian. Other Armenians were members of the Austrian Parliament.

At the end of the 18th century, the war between Russia and Turkey led (in 1789) to the migration of Armenians from Cetatea Alba to Tighina and later on to Dubasari, on the Nistru/Dnestr river. They then settled in the town of Grigoriopol, founded in 1792 by Joseph Argutian, the bishop of Armenians in Russia. In Grigoriopol, Armenians built three churches, dedicated to St Catherine (an homage to the empress Catherine the Great), the Holy Cross and St Gregory the Enlightener. The town was given special privileges by Catherine the Great and Paul I, and attracted Armenians from Ismail, Chilia, Tighina and Causani. Most of the privileges never actually materialized, and the bulk of the Armenian community in Grigoriopol moved to Chisinau during the first half of the 19th century.

In 1812 the eastern part of Moldavia was annexed by the Russian Empire and given the name of Bessarabia (Basarabia in Romanian). The territory had over 2,000 Armenians. An Armenian born in Bulgaria, in Ruschuk/Ruse, Manuc Bey Mirzaian, played an important an controversial role in the peace negotiations in Bucharest. Accused of treason by the Turks, he fled to Bessarabia and settled in Hancesti, where he built a castle. His plans to build a new town close to Reni, on the Danube, with a special place for Armenians, were never put into practice; Manuc died unexpectedly in 1817 and was buried in the Armenian church in Chisinau.

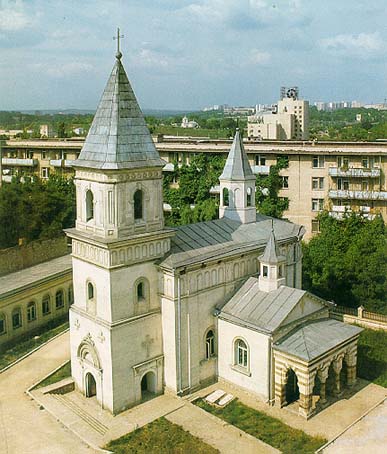

In the new capital of Bessarabia, Chisinau, Armenians had settled as early as the 17th century. There was an Armenian street in the old commercial center of the town. Armenians also had their own church, dedicated to St Mary and built in 1804, on a site between the Turkish street and Constantin Street. The church may have been built on the ruins of the Romanian church of St Nicholas, built in 1645 and destroyed by Tartar invasions in the 18th century. Armenians may have purchased the ruins and built their own church.

An Armenian archbishopric was established in Chisinau. It also included Armenians from a large part of the Russian Empire, including Nor Nakhichevan, Moscow and St Petersburg. Armenians received a large piece of land in the new, upper part of the town, which came to be known as the “Armenian courtyard”. It served as the bishop’s residence and a community center; part of the land and houses was also rented. The income was used – during the second part of te 19th century – to support the Guevorguian Academy in Echmiadzin. In 1858, according to official numbers, there were 2275 Armenians in Bessarabia, 1100 of which lived in Chisinau.

While some of the Bessarabian Armenians moved to the remaining part of the Moldavian principality, new Armenians settled in Bessarabia, and their number increased to some limited extent over the 19th century. The presence of Armenian bishops was an important factor (towards the end of the century, however, the see remained vacant for long intervals). Josep Argutian was named Catholicos but died on the way to Ecmiadzin in 1801. The next bishop was Grigor Zaharian born in Cetatea Alba, who played an active part in the fight for in influence in Echmiadzin and died in 1827. He was followed by the most famous of all Chisinau bishops, the future Catolicos Nerses Ashtaraketsi. The next ead of the Armenian church in the area was Gabriel Aivazovski, who played an important role in the establishment of te Halibian College in Kaffa/Feodosia in Crimea, that became an important centre for the education of young Armenians from neighbouring regions, including Moldavia and Wallacia. Between 1878 and 1885 the archbishop of Chisinau was the future Catholicos Macar I Ter-Petrosian. New churches were built in Orhei (St Mary, around 1830 renovated in 1903), Balti (St Gregory the Enlightener, 1913, due to Dimitrie-Mgrdich Lusahanian/Lusavanovici), Hancesti (St Mary, built by Manuc Bey, rebuilt in 1871, destroyed in 1941). Catholic Armenians had their own church in Hotin. There also were several Armenian schools in Bessarabia, for instance those in Chisinau and Cetatea Alba. Armenians were lawyers, doctors, landowners, merchants. The best inn, actually a Swiss-style hotel, belonged to the Muraciov (Muradian) family. After a long and brilliant history, it was destroyed in 1940. Among the most important families in Bessarabia were the Deleanovs (Delanian), the Ohanovs (Ohanian), the Lebedevs, the Anush, the Muratovs (Muratian), the Muraciovs (Muradian), the Lusahanovs and the Ianusievicis.

The beginning of the 19th century was a period of cultural and economic revival for Armenians in Moldavia and Wallachia. In Moldavia Armenian schools were opened in Iasi (1803, near the newly renovated church of St Mary), Suceava (1823), Roman (1841), Botosani (1843), Focsani (1847, school for girls in 1860), Galati, Bacau, Targu-Ocna. In 1841, Armenian schools were included in the Moldavian public education system and Armenians were allowed to attend the developing Moldavian system of higher education. Cristea Karacas founded in Iasi a private college that would soon become the town’s leading private school. In Bucharest, the Armenian school was (re)opened in 1800, and reorganized in 1817 due to the donations of Manuc Bey Mirzaian. A new building was inaugurated in 1847; it was financed by Varteres Amira Misakian, an Armenian born in Constantinople. The Armenian population – especially that in Wallachia – was increased due to the immigration of Armenians from Bulgaria and other regions on the Ottoman empire at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century.

The Armenian churches in Moldavia and Wallachia were under the supervision of clerics nominated by the Armenian Patriarchy o Constantinople and local councils. The development of Moldavian towns – and their Armenian communities – led to the building of Armenian churches in Herta (taken over by Romanians in 1814) and Bacau (St Michael and Gabriel in Armenian Street, 1848-1858, demolished by the Communist authorities in 1977). Armenian books were also printed in Iasi in Gheorghe Asachi’s workshop. An act adopted before the union of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859 proclaimed the equal rights of all Christian subjects in the principalities. Armenian guilds and professional and cultural associations (such as those in Iasi, Suceava, Bacau, Roman) played an important role in the life of the community. They contributed to the preservation of Armenian heritage. For instance, the Young Armenians’ guild in several Moldavian towns set rules and obligations for the young members of the community. For instance, they were obliged to visit all Armenian houses and sing carols for Christmas every year; those who did not attend had to pay a fine. Quite obviously, they also had to attend local Armenian schools. The “Azkasirats” (Patriots’) Society was founded in Iasi in 1868. It had branches in Botosani, Bacau, Roman, Targu Frumos, Tecuci. There were also several Armenian associations in Bucharest: “Ser hanun Isusi” (1833), “Hayrenasirats ingerutyun” (1837), “Ararat” (1838), “Usumnasirats ingerutyun Ararat” (1843), “Usumnasirats ingerutyun” (1871), “Armenia” (1879), “Ararat” (1886), “Arax” (1901), “Arevdragan ingerutyun” (1903), the amateur theatre “Sokhag” (1911), “Mangaser dignants miutyun” (1912), the Armenian Red Cross (1920), the Young Armenians’ Assocation (1920), the “Ararat” Library (1921).

Armenians also played an active and at times impressive role in the economic and cultural development of the principalities. Several wealthy and cultured Armenian families, such as Buiucliu, Goilav, Missir, Pruncu, Aburel, Manea, Burdea, Ciuntu, Ciomac, Kessim, Samurcas, Trancu, Socor, Mortun, Taranu, Ursu, Gaina, Sava, Cerchez, Negruzzi provided several generations of local notables, supporters and producers of Romanian culture, members of parliament, mayors, army officers. Gheorghe Asachi, a founder of the Romanian educational system in Moldavia and a great contributor to many cultural developments, Vasile Conta, the atheist philosopher son of an Armenian priest, Spiru Haret, the best Romanian education minister and the first Romanian to get a PhD in Mathematics, Garabet Ibraileanu, the leader of the “Viata Romaneasca” literary group and one of the greatest Romanian literary critics, the architect Cristofi Cerchez, the musicians Carol Miculi and Mihail Jora, the painter Theodor Aman are among the most important personalities in Romanian culture in the 19th century.

The second half of the 19th century was not as good for the preservation of Armenian identity in Moldavia and Wallachia as it may have been expected from earlier developments. The northern part of Moldavia, the old core of the Armenian community of Romania, lost ground in economic terms and Armenian communities in the area entered a period of slow, gentle decay. In 1850 the Armenian school had two priests; by the end of the century it only had one. The second Armenian church, St Gregory the Enlightener, was destroyed during the great fire of 1827. Plans to rebuild it and to build a school for girls beside it were eventually abandoned and the ruins were demolished in 1899. The development of the Romanian public education system led to the decrease in the number of pupils in Armenian schools. The Armenian school in Bucharest was closed in 1899. Knowledge of the Armenian language gradually decreased and the old local Armenian dialect slowly died out. For a while, some Armenians send to each other letters in Romanian written in Armenian alphabet.

In Transylvania, the 19th century was less favourable for Armenians than the 18th century. Armenians gradually lost the privileges that had protected their communities. In 1801, Armenians were forbidden to use their language in their language; quite soon, they were also forbidden to keep their accounts in Armenian. In Elisabethopolis, Armenian was replaced by Hungarian and Latin in the local public school in 1811; only the Mkhitarist school preserved Armenian as a language for teaching. In Armenopolis, an Armenian elementary school was reopened in 1860 and was closed down around 1890; a primary school existed between the First World War and 1940. The economic situation also changed in Transylvania, which – around the middle of the century – was somehow left behind the industrialization process. The peace treaty of Adrianople and the lifting of the Turkish monopoly over Moldavian and Wallachian trade moved the commercial centre of the region towards Bucharest. Armenian merchants were confronted with the competition of Greek, Aromanian/Vlach and later on local Romanian tradesmen. Many young Armenians had to leave their native towns and look for jobs in other places; their Catholic faith made assimilation easier. Non-Armenians were allowed to settle in the previously ‘closed’ towns.

Armenians in Armenopolis/Gherla had been given a precious painting by Rubens as a prize for their financial assistance to the Austrian Crown in difficult times. By the revolution of 1848, relations between Armenians and the Austrian authorities had already deteriorated to some extent. In 1848, the Hungarian revolutionary government appointed George Simaian as the man in charge of ethnic minorities in Transylvania. Stepan Korove (Koroveian) was one of the authors of the Hungarian declaration of independence. Kiss Erno and Lazar Vilmos were executed for their role in the revolution and became Hungarian national heroes, while General Czecz Janos died in exile in Argentina. The town of Elisabethopolis was severely damaged during the fighting between imperial and revolutionary armies, and Armenopolis was made to pay a huge fine. The economy of the two towns never quite recovered after these events. Armenians in Transylvania became gradually Magyarized, as the strong traditional factors represented by extended family structures, Armenian schools and guilds gradually weakened. Among the main Armenian personalities of the century one can mention Lukacsi Kristof, the headmaster of the high school in Armenopolis and the author of the History of Armenians in Transylvania, Grigor Covriguian, the abbot of the monastery of San Lazzaro in Venice, Czecz Anton and Volf Gabriel, famous botanists, the painter Hollosy Simon.

Towards the end of the century Armenians in Transylvania – mainly those in Armenopolis – tried to revive their traditions. An Armenian Museum and an Armenian journal (“Armenia”, in Hungarian) were founded. Most of this initial energy did not however outlive the death of the main artisan of the Armenian revival, Szongott Kristof (Khachik Asdvadzadurian). (1843 – 1907).

The massacres of 1895 and the genocide of 1915 brought new waves of Armenian refugees to Romania. In 1915, Romania was the first country to officially offer asylum to Armenian refugees. It was also one of the 15 countries that accepted Nansen passports. After 1916, when Romania joined the Entente, many of newly arrived Armenians served as volunteers in the Romanian army, although they were not yet Romanian citizens. The Armenian community set up an orphanage in Strunga aimed at saving children who had lost their parents during the genocide.

The bulk of the ‘new Armenians’ settled in Bucharest and Constanta, although some of them spread to other towns in Romania. They revived Armenian community life, churches and schools. The new Armenian church in Bucharest, in traditional Armenian style (based on the Cathedral in Echmiadzin), was inaugurated in 1915. The Armenian school in Bucharest was reopened due to the donation of Mrs Kesimian (hence the name of the “Misakian-Kesimian School”). Around 1900, it had 250 pupils; in 1932 there were 405.

Armenians had their own press, sports clubs, choirs, amateur theatres. Here are some Armenian publications from this era: “Maro” (1906), “Ararat” (1907), “Shepor” (1912-1913), “Hayastani artzakank” (1913-1914), “Arax” (1915), “Incnavar Hayastan” (1916), “The Romanian-Armenian Almanac” (1914-1916), “Nor Arshaluys” (1922-1933), “Ararat” (1924-1942), Kharazan” (1921), “Masis” (1920-1922), “Caghuti tzayn” (1923), “Paros” (1924), “Yergir” (1925, 1926, 1929), “Titzavan” (1923) – a literary journal, “Ari” (1923-1926), a sports magazine, “Karun” (1925), “Meghu” (1925), “Or” (1926-1929), “Hrazdan” (1927), “Dashnaktzutyun Or” (1928), “Hayastan” (1927-1930), “Navasart” (1923-1925), “Azad pem” (1932), “Herg” (1937-1938), “Nor Ughi” (1934), “Araz” (1932-1944), “Hay Mamul” (1934-1938), “Sevan” (1950-1958).

In 1918, the provinces of Bessarabia, Bucovina, Transylvania and Banat were united to Romania. The representative of Armenians in the Bessarabian assembly, Petre Bajbeu-Melikov, mayor of Orhei, supported the union. Another representative of Bessarabian Armenians, the lawyer Andrei Barhudarov, took part in the Armenian assembly in Kiev that stated its support for the independence of the Armenian Republic. Armenians in Bessarabia set up the National Committee of Armenians in Bessarabia (NaCoBa), which administered the Armenian patrimony, churches and schools, and prepared Armenian students for the Romanian curriculum.

The Armenian bishop in Chisinau, Husig Zohrabian, moved to Bucharest in 1920 as head of the reorganized Archbishopric of Armenians in Romania. One of his successors, Vasken Balgian, would become Catholicos in 1955. The Armenian Catholic Church was given a new and improved statute, with 5 parishes and 36,000 faithful. A nw Armenian Catholic chapel was built in Bucharest in 1933. Due to a misintepretation of the Romanian land reform, the “Armenian courtyard” in Chisinau was taken from the Armenian community. Its fate would remain uncertain through a long series of trials until 1940.

The 20th century was also rich in Armenian personalities in Romania. A complete list is impossible, and a full one is impossible. Here are some examples: the first Labour Minister, Grigore Trancu-Iasi, his sister, the first Romanian woman-surgeon, Marta Trancu-Rainer, the founder of the surgery school in Cluj and the rector of the local university, Iacob Iacobovici, the founder of gerontology, Ana Aslan, the founder of the Romanian allergology school, Ervant Sevropian, the art collectors Krikor Zambaccian, Hrandt Avakian and Garabet Avakian, the great historian Hagop Djololian Siruni, Haig Acterian, Ion Sahighian, Ion Sava, all personalities of Romania theatre, the famous opera singers David Ohanesian and Garbis Zobian, the painter Nutzi Acontz, the sculptor Ioana Kasargian, the publicist Vartan Mestugian, the Armenian Catholic scholar Magardici Bodurian, the writers Stefan Agopian and Bedros Horasangian, the businessmen Armenac Manissalian, Vartbaronian, Frenkian, Israelian, Danielian.

By 1940 there were about 40,000 Armenians in Romania. It was a rather heterogeneous, but very much alive community, with a long history and a rich heritage. The Second World War brought a new, communist regime to Romania. In 1945 some Armenians from Romania moved to Soviet Armenia. Armenian communities were seriously weakened by the elimination of private businesses in Romania, which deprived them of their traditional economic autonomy. A “Democratic Committee” was set up for each ethnic minority in Romania, Armenians included (the Armenian one actually lasted longer than the other ones, due to its role in the … distribution of the Soviet press…) Some of the wealthiest Armenians became targets of the new political regime.

The gloomy political and economic environment led to mass migration; by the 1980s there were perhaps more “Romanian” Armenians in the US than in Romania. The number of mixed marriages also increased. Around 1980, there were 3 baptisms and over 20 Armenian burials per year in Bucharest. In 1964, the last Armenian schools, those in Bucharest and Constanta, fell victim to a “nationalist” bout of the local communist regime. Armenian language classes continued in an informal manner, with the support of the Armenian church.

The regime change in 1989 brought a change in the institutional environment. The Union of Armenians in Romania has a representative in the Romanian parliament (provided it gets more than 3500 votes; election results: 1992: 7200 votes, 1996: 11,000, 2000: 21,000). Between 1996 and 2000 there were actually two Armenian MPs in the Romanian parliament. There are two Armenian publications: “Ararat” (in Romanian) and “Nor Ghiank” (in Armenian), both subsidized by the government. The Armenian library and cultural centre in Bucharest was reopened; so were the Armenian schools in Bucharest and Constanta. Armenian language courses were also organized in Cluj and Pitesti. The Armenian community had its own (quite active) publishing house. Main community events include the pilgrimage to the monastery of Hagigadar, the celebration of St Gregory the Illuminator in Gherla/Armenopolis and St James in Botosani.

In spite of this favourable external environment, the situation of the Armenian community in Romania remains dire and its future uncertain. There are indeed very few Armenians left in Romania, and the knowledge of Armenian is extremely limited (fewer than 1000 native speakers). Many of the younger Armenians actually come from mixed marriages. The not-so-brilliant economic situation of the country has failed to attract an influx of ‘new’ Armenians – as it happened in Poland or Hungary. Some of the Armenian communities, such as the 600-year old community in Roman, are almost extinct. The situation of the Armenian monuments in Romania is also critical – a few examples are the St Mary church in Iasi, the churches in Botosani, the St Simon church in Suceava…

Bibliography:

1. Gheorghe Bezveconnai – Armenii in Basarabia. Eparhia nahicevaniana si basarabeana. Manuc-Bei (Armenians in Bessarabia. The Eparchy of Nor Nakhichevan and Bessarabia. Manuc Bey), Colectia “Din trecutul nostru”, editata de Asociatia Cultural-Istorica “Neculai Milescu”, Chisinau, January 1934

2. Neagu Djuvara – Intre Orient si Occident. Tarile Romane la inceputul epocii moderne (Between East and West. The Romanian Principalities at the Beginning of the Modern Era), Editura Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995

3. Tigran Grigorian – Istoria si cultura poporului armean (The History and Culture of the Armenian People), Editura Stiintifica, Bucharest 1993

4. Lica Sainciuc – Colina antenelor de bruiaj (The Jamming Aerials Hill), Editura Museum, Chisinau, 2000

5. Sergiu Selian – Schita istorica a comunitatii armene din Romania (A Historical Sketch of the Armenian Community in Romania), Editura Ararat, Bucharest, 1999

Source: personal.ceu.hu