The Eastern Crisis

In the summer of 1875 the Christian peasantry of Bosnia and Herzegovina rose in revolt against their Muslim landlords. The revolt dragged on until the winter; the Porte appeared unable to control it. On 30 December 1875 Count Andrassy, Austro-Hungarian minister of foreign affairs, proposed in a note a fair system of government for the rebellious provinces, whereby a just solution could be found for the peasants’ grievances. All the great powers agreed to align themselves behind Andrassy except Britain which demurred, and, although eventually agreeing to Andrassy’s proposals, made no attempt to persuade the Ottoman government to accept them.

The note, like many other reform schemes forced on Ottoman Turkey and accepted by the Porte, had no practical result. Indeed the situation grew worse; consequently Andrassy and his Russian opposite number, the elderly Prince Gorchakov, met in Berlin and devised a memorandum which was along the same lines as the Andrassy note, but stronger. It was accepted at once by France and Italy, but this time entirely rejected by Britain. Disraeli, in a phrase of silly hysteria, complained that the northern powers of Russia, Austria and Germany were ‘asking us to sanction them in putting a knife to the throat of Turkey, whether we like it or not’.71

The crisis intensified. There was a rising in Bulgaria in April 1876, which was cruelly put down by Ottoman irregulars, despatched on orders from Constantinople. Queen Victoria, apparently troubled by qualms of conscience, wrote of this incident:

Hearing as we do all the undercurrent, and knowing as we do that Russia instigated this insurrection which caused the cruelty of the Turks, it ought to be brought home to Russia, and the world ought to know that on their shoulders and not on ours rests the blood of the murdered Bulgarians!

In fact the rebellion had been organised by Bulgarian émigrés. In its suppression about sixty villages were destroyed and 12,000 to 15,000 massacred – men, women and children, old and young. In one notorious incident 1,200 people had gathered in a church for protection, and had been burnt alive there.

Immense anti-Turkish agitation followed the publication of the facts of the atrocities (which Disraeli insisted on terming ‘so-called atrocities’). The indignation would not die down, even though Disraeli tried to dismiss it as mere ‘coffee-house babble’. Best remembered today of the expressions of revulsion for what the Turks had done in Bulgaria is Gladstone’s pamphlet The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, which called for the Turkish government to carry itself off bag and baggage. It did not appear until September 1876, after the publication of a British Embassy report had persuaded Gladstone that the allegations were true. The pamphlet sold 200,000 copies in a month.

The power of popular agitation over the Ottoman government’s repression of the Bulgarian uprising was by the late summer of 1876 such as to persuade Disraeli that a conference was needed to discuss the ills of the Ottoman empire. These at this time were manifold: Serbia had declared war on Turkey in June, and Montenegro had joined her in early July. Constantinople was in a state of political turmoil: earlier in the year the grand vizier and Sheikh ul-Islam (the supreme religious dignitary in the empire) had been driven from office; then Sultan Abdul Aziz himself was deposed (30 May). Two weeks later both the foreign and war ministers were murdered. At the end of August the new sultan, Murad, who had turned out to be feeble-minded, was deposed, and his half-brother, Abdul Hamid, was invested as sultan. ‘Will he be a Solyman the Great?’ asked Disraeli of the man whose paranoia and cowardice were to be the main distinguishing feature of Near Eastern politics for the next thirty years.

So Disraeli decided ‘there must be a conference, ‘ I hate it’, adding I am quite confident we have managed without it, had it not been for this Bulgarian bogey. Lord Salisbury was to be British delegate. The conference eventually met in December 1876 in Constantinople. Its agenda was wholly concerned with the administration of European Turkey; Armenia had not yet come under the scrutiny of the powers.

Then – the Turkish master-stroke: during the conference, on 23 December, the guns boomed out, and the Ottoman constitution was proclaimed, a liberal and democratic instrument. The conference was now redundant, the presence of the powers superfluous: here was the easy way out that Disraeli and his ambassador, Elliot, had hoped for. The administrative reforms that the powers were seeking to impose on the Ottoman empire were now, apparently, being created by her own political institutions. The powers were disunited; even the British disagreed amongst themselves. Salisbury requested that the British fleet be sent to Constantinople to compel the sultan to introduce reforms; Disraeli refused.

The conference broke up in late January 1877. Nothing had been achieved; and the Ottoman constitution, wheeled in at a critical moment, like a gigantic piece of stage scenery (depicting, perhaps, contented sunlit villages, fertile valleys) was wheeled out some months later, and the familiar Ottoman provincial backdrop was visible again, of local tyranny, extortion, oppression, wrecked homes, burnt fields, homeless refugees.

The lesson of the Constantinople conference (which none of the powers drew) was that the Ottoman empire was still a sovereign power. However much Europe, through her capitulations, her ‘spheres of influence’ and her financial involvement might think she controlled Turkey, the Ottoman government could still over-trump the powers with her own laws and ‘assurances’, especially if a power such as Britain were only to make a show of insistence. Whether or not Turkey’s laws were sham was at this stage irrelevant; all she had to do was to convince the powers until they departed. Once the foreigners had gone, the laws could be quietly dropped. The powers were enormously reluctant to draw the conclusion before their eyes about Ottoman Turkey: that the only way to reform the administration of a Turkish territory was to detach it from the sovereignty of Turkey. They would not see this, since they needed a large Turkey to contain their own jealous rivalries, and to produce as large a return on their investments as possible. The method that they chose, of trying to impose schemes of reform, was the worst possible, since it achieved nothing, and only left the wretched subject peoples more resented and hated by both central and provincial Ottoman rulers.

Only one power was prepared to abandon vacuous diplomacy for action.

The Russo–Turkish War of 1877-1878

Our faithful and beloved subjects know the lively interest which we have always devoted to the destinies of the oppressed Christian population of Turkey. … We made it pre-eminently our object to attain the amelioration of the condition of the Christians in the east by means of peaceful negotiations and concerted action with the great European powers, our allies and friends. During two years we have made incessant efforts to induce the Porte to adopt such reforms as would protect the Christians of Bosnia, Herzegovina and Bulgaria from the arbitrary rule of the local authorities. The execution of these reforms followed, as a direct obligation, from the anterior engagements solemnly contracted by the Porte in the sight of all

Europe. Our efforts, although supported by the joint diplomatic representations of other governments, have not attained the desired end. The Porte has remained immovable in its categorical refusal of every effectual guarantee for the security of its Christian subjects, and it rejected the demands of the conference of Constantinople. … Having exhausted our peaceful efforts, we are obliged by the haughty obstinacy of the Porte to proceed to more determined action, The sentiment of equity and that of our own dignity render it imperative. Turkey, by its refusal, places us under the necessity of having recourse to arms. … We expressed our intention of acting independently should we deem it necessary, and should the honour of Russia require it. Today, in invoking the blessing of God upon our valiant armies, we give them the order to cross the frontier of Turkey.

With these words Alexander II, the tsar-liberator, declared war on the Ottoman empire on 24 April 1877. All the Slav peoples looked to Russia for deliverance from Turkey. But among the Armenians there was not the same unanimity. Some genuinely feared that if they were annexed by Russia they would be swallowed by Orthodoxy, despite the statutes by which the Russians regulated the affairs of the Armenian Church. On the outbreak of the war, the Armenian patriarch Nerses Varzhabedian issued a pastoral letter calling on his flock to show loyalty to the Ottoman state, and to work and pray for an Ottoman victory. However, there is little doubt that in the east, at peasant level, the vast majority of the Armenian villagers wanted an end of the corrupt tyranny which ruled them. Arminius Vambéry, no lover of the Armenians, made his first journey east in 1862; stopping at a village near Diadin (a few kilometres west of Bayazet) he saw how downtrodden the Armenians were. On asking them why they did not ask assistance of the governor of Erzerum, [I] was told in reply, ‘that the governor himself was at the head of the thieves. God alone, and his representative on earth, the Russian tsar, can help us’. And the poor people were certainly right in this.

The war was disastrous for Turkey. In Europe Russian forces reached the outskirts of Constantinople, and in Asia they reached Erzerum. Many observers believed that the Ottoman empire was on the point of collapse. Liberals wondered whether Britain was again going to be forced to shore up an antiquated despotism for dubious strategic and financial returns. They sought co-operation with Russia in bringing about an eastern solution.

This, however, was the last thing that Disraeli and the Queen intended. Some of Disraeli’s utterances bring to mind Trajan campaigning in Asia, driven by a mad passion for glory and prestige. ‘The Empress of India should order her armies to clear Central Asia of the Muscovites, and drive them into the Caspian,’ he wrote to his sovereign on 22 July 1877. Three weeks later, at a Cabinet meeting, he observed that a British force could be sent to Batum, ‘march without difficulty through Armenia, and menace the Asiatic possessions of Russia’. It was clear that he would envisage no solution with Russia other than one based on maximum confrontation.

He did, however, stop short of actually declaring war on Russia, thereby saving Britain from a fruitless replay of the Crimean war; though more than once he hinted to Turkey that there might be British help against Russia. Other than sending the fleet through the Dardanelles in January 1878 – and promptly having it ordered out again by the sultan, to the amusement of the statesmen of Europe – British support for Turkey was merely verbal and diplomatic.

The Armenians at the Close of the War

After the fall of Plevna (Bulgaria) on 11 December 1877, Russian troops advanced onward to the Ottoman capital; only an armistice, agreed on 27 January 1878 and signed on the 31st, halted them at Adrianople (Edirne). On the same day the ‘preliminary bases of peace’ between the parties were signed.86 Bulgaria was to be autonomous, Montenegro, Romania and Serbia independent, and Bosnia and Herzegovina were to receive autonomous administrations. But there was no mention of Armenia, since the Armenians had not yet made any requests known.

The Armenian leadership resolved to change this. Although they had been loyal to the Porte at the start of the war – a position which had served their own interests – circumstances had changed this. The principal factor was the behaviour of the Kurdish irregular cavalry, which was in the pay of the Turkish regular forces commanded by Ahmed Mukhtar Pasha. C. B. Norman, special correspondent for The Times, wrote on 26 July 1877 that between his camp at Sabatan and Köprüköy (respectively 25 kilometres east and 40 kilometres west of Kars),

I have not seen one Christian village which has not been abandoned in consequence of the cruelties committed on the inhabitants. All have been ransacked, many burnt, upwards of 5,000 Christians in the Van district have fled to Russian territory, and women and children are wandering about naked.

In other words the Kurds, far from aiding the Ottoman war effort, had gone on the rampage, looting and murdering Armenian villagers. (The incidental consequence for the Ottoman army was near starvation, since many of the Armenians’ flocks and herds, as well as their stores of grain, were pillaged.)

When these actions became known to the Armenian leaders in Constantinople – they were the subject of a debate in the Ottoman parliament just before it was disbanded by the sultan – attitudes shifted. The Turkish government had permitted the destruction of numerous Armenian villages in the east; and the Turkish army was being defeated by the Russians. Hence the Armenian National Assembly authorised the patriarch to send a delegation to the Grand Duke Nicolas, at his headquarters in Adrianople. There, through the energetic mediation of Count Ignatyev, the leading pan-Slavist who was Russian ambassador to Constantinople, a clause was drawn up for inclusion in the forthcoming peace treaty, which read:

For the purpose of preventing oppressions and atrocities that have taken place in Turkey’s European and Asiatic provinces, the sultan guarantees, in agreement with the tsar, to grant administrative local self-government to the provinces inhabited by Armenians.

San Stefano and its Aftermath

But Ottoman Turkey refused to countenance local self-government. Throughout February 1878 great-power tension was at its height, and the likelihood of and Anglo–Russian clash of arms most acute. Turkey, although defeated in the war, could afford to say what was or was not acceptable; and to the Russians the matter was not sufficiently important for them to push it at all costs. A visit by the Armenian patriarch himself failed to convince the Russians of the need to insist on local self-government. Ultimately, Russia and Turkey agreed on the wording of the article. In the peace treaty, signed at San Stefano (the modern Yeshilköy, site of Istanbul’s international airport) on 3 March 1878, article 16 reads:

As the evacuation by the Russian troops of the territory which they occupy in Armenia, and which is to be restored to Turkey, might give rise to conflicts and complications detrimental to the maintenance of good relations between the two countries, the Sublime Porte engages to carry into effect, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by Armenians, and to guarantee their security from Kurds and Circassians.

Russian territorial acquisitions in Asia were extensive; in the south, Bayazid and the vale of Alashkert, as far west as Khorasan; the fortress town of Kars (captured by the Russians for the third time in 50 years), and Sarikamish (T.: ‘yellow reed’); Olti, and in the north Artvin and the harbour town of Batum.

As soon as the British Cabinet received a copy of the treaty (23 March), it opposed it vigorously, though the Cabinet was far from united on the issues. Disraeli himself proposed declaring an emergency, putting a force into the field, and sending an expedition to occupy Cyprus and Alexandretta (Iskenderun) – specifically with the intention of counterbalancing the alleged effect of the Russian conquests in Armenia. But the first systematic attack on the treaty of San Stefano was made by Lord Salisbury in his circular of 1 April 1878, the day after he assumed the office of foreign secretary.

Salisbury attacked every proposal of the treaty, and demanded that the issues be settled by a European congress. His opposition to the Russian territorial gains in Armenia was twofold:

The acquisition of the strongholds of Armenia will place the population of the province under the immediate influence of the Power which holds them; while the extensive European trade which now passes from Trebizond to Persia will, in consequence of the cessions in Kurdistan, be liable to be arrested at the pleasure of the Russian government by the prohibitory barriers of their commercial system.

In reply to Salisbury’s circular Prince Gorchakov, his Russian opposite number, said that the Russian acquisitions in Armenia possessed only defensive value. (Strategically speaking, this is undoubtedly correct.) Gorchakov admitted himself perplexed by the British view on the caravan route through the vale of Alashkert, saying that it was in contradiction to former British government assertions that Russian possession of even Erzerum or Trebizond would not constitute a danger to British interests. To affirm that, with the vale of Alashkert, Russia would be in a position to wreck the trade of Europe was to carry distrust to an extreme.

To resolve the differences of the great powers, it was decided to hold a congress. It would be at Berlin, with Prince Bismarck presiding as ‘honest broker’. The lines of the Asiatic frontier between Russia and Turkey were, however, agreed beforehand. Russia would keep Kars, Ardahan and Batum, but Alashkert and Bayazid would revert to Turkey (so that Britain could keep her commercial route intact).

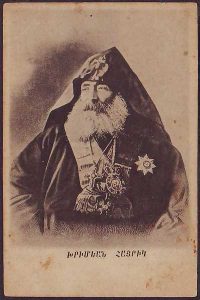

Armenian leaders in Constantinople had felt their hopes for their people slipping with time. So an Armenian delegation, headed by ex-patriarch Khrimian, set out in March to acquaint European capitals with their proposals for Turkish Armenia. These were, as they had hoped at Adrianople, for some form of local self-government within the framework of the Ottoman empire, and for a strengthening of the forces of law and order.97 But the leaders of Europe showed little interest in the cause of the Armenians – a people who had remained pacific, despite misgovernment. From April to June the Armenian leaders were in England, and met Lord Salisbury on 10 May; he gave them no more than platitudinous assurances.98 British policy had more important things to deal with than humanitarian matters.

The Congress of Berlin and the Revelation of the Cyprus Convention

The Armenian delegates travelled on to Berlin, where the congress opened on 13 June. Their presence went unheeded, at this last occasion on which the great Map 4. The Romanov-Ottoman Frontier in Asia, according to the Treaties of Adrianople, San Stefano and Berlin powers disposed of the affairs of the Near East without the presence of the people who actually lived there; and the Armenians witnessed, in the treaty consequent to the deliberations of the congress, the final whittling down of their hopes for the secure and ordered advancement of their people.

There was, however, one bit of business that the statesmen assembled in Berlin had to dispose of before their serious discussion could begin. This was the revelation, which occurred the day after the opening of the congress, that the British had undertaken a secret bilateral agreement with Turkey, promising to defend the Asiatic frontier in the event of a Russian attack, and receiving in return the lease of the island of Cyprus. The disclosure of the agreement – it was leaked to the press by an underpaid clerk – proved highly embarrassing for the British delegation. In the words of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt:

When the congress met in Berlin in the early summer of 1878, one of the first acts was to take from each of the ambassadors present a declaration that he came to it with clean hands – that is to say, free of all secret engagements between his government and any other government represented at the congress. This declaration Lord Beaconsfield and Lord Salisbury gave with the rest.

A few days after, however, the text of the Cyprus Convention was published in London by the Globe newspaper … The incident was within a little of breaking up the congress. The French and Russian ambassadors declared themselves outraged at the English ill-faith, and M. Waddington [the chief French delegate] went so far as to order his trunks to be packed for leaving Berlin.

(The situation was only saved by the intervention of Bismarck, who negotiated a package of concessions for France, which included giving her a free hand in Tunis.)

The Cyprus Convention, which had been signed on 4 June, just five days after Britain and Russia had agreed on the position of the Asiatic frontier, was of immense importance as regards both the responsibilities of Britain and the aspirations of the Armenians for the secure government of Turkish Armenia. Its two significant paragraphs read:

If Batum, Ardahan, Kars or any of them shall be retained by Russia, and if any attempt shall be made at any future time by Russia to take possession of any further territories of his imperial majesty the sultan in Asia, as fixed by the definitive treaty of peace, England engages to join his imperial majesty the sultan in defending them by force of arms.

In return, his imperial majesty the sultan promises to England to introduce necessary reforms, to be agreed upon later between the two powers, into the government, and for the protection of the Christian and other subjects of the Porte in these territories.

Britain undertook to defend Ottoman Turkey (as the cartoon from Punch shows); in return she obtained not only Cyprus – ‘a place of arms in the Levant’, in the words of Sir Stafford Northcote – but also a pledge from the sultan to ‘introduce reforms’. Now, those who have studied former Ottoman reform schemes might view this new undertaking with scepticism. In comparison with the undertaking to Russia, as shown in article 16 of the San Stefano treaty, that to Britain was feeble, since in the former case there was an army in occupation, whereas there was no such British force to compel the sultan. And Britain had never shown much zeal in persuading Turkey to implement reforms.

Despite the apparent manner in which Britain had eclipsed Russia as the guarantor of reforms in Asia, the congress found it necessary to include the matter in its deliberations. At the session of 4 July Lord Salisbury raised the question of revising the relevant article of the San Stefano treaty. He was happy about its second half (which laid down that the Ottoman government would introduce reforms without delay), but could not accept that the evacuation of Russian troops was to be conditional on the introduction of the reforms. Russian troops, which to the Armenians of the provinces were the only guarantee against lawlessness, were to the British an object of obsessive imperial jealousy.

Two days later Salisbury indicated that he was planning to substitute for the guarantee of Russian military occupation one that said that Turkey would merely ‘come to an agreement’ with the great powers on the scope and execution of reforms. Nothing would be done to compel the Porte to act. Why Ottoman Turkey had to promise to reform both to Britain alone (in the Cyprus Convention) and to all six great powers together is puzzling; but to have only the former guarantee would make Britain’s imperial concern embarrassingly plain; and moreover with the latter, when the reform scheme failed, the British prime minister could always point to the responsibility of all the powers, dismissing the Cyprus Convention with a remark such as ‘We cannot say that we are the protectors of Turkey, or that the influence of a guardian over his ward is one that we can claim to exercise,’ – as Lord Salisbury was to say on 28 June 1889.

The text of the article on Armenian reforms, which was to become article 61 of the treaty of Berlin, was agreed on 8 July. It read:

The Sublime Porte undertakes to carry out, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local requirements in the provinces inhabited by Armenians, and to guarantee their security against the Circassians and Kurds.

It will periodically make known the steps taken to this effect to the powers, who will superintend their application.

This article, together with the Cyprus Convention, brought the Armenians

no security at all. The government of Turkish Armenia, if anything, deteriorated after their signature. In turn, Armenian self-defence groups and revolutionary societies grew up, provoking heavy retaliation. The most common British attitude was of studied ineffectualness; and Russia, partly for internal reasons and partly for the threats from Britain contained in the Cyprus Convention, refused to go to the aid of Turkish Armenians.

Expressing its deep disquiet at the text of article 61 of the treaty, the unheard Armenian delegation sent a protest note to all the plenipotentiaries, on 13 July, the day the treaty was signed:

The Armenian delegation expresses its regrets that its legitimate demands, so moderate at the time, have not been agreed upon by the congress. We had not believed that a nation like ours, composed of several million souls, which has not so far been the instrument of any foreign power, which, although much more oppressed than the other Christian populations has caused no trouble to the Ottoman government (and, although our nation had no tie of religion or origin to any of the great powers, yet, being a Christian nation it had hoped to find in our century the same protection afforded to the other Christian nations) – we had not believed that such a nation, devoid of all political ambition, would have to acquire the right of living its life and of being governed on its ancestral land by Armenian officials.

The Armenians have just realised that they have been deceived, that their rights have not been recognised, because they have been pacific; that the maintenance of the independence of their ancient church and nationality have advanced them nothing.

The Armenian delegation is going to return to the east, taking this lesson with it. It declares nevertheless that the Armenian people will never cease from crying out until Europe gives its legitimate demands satisfaction.

Disraeli, for his part, returned to England to tumultuous cheering crowds. He assured his adoring public that he had brought ‘peace with honour’ – a claim which, in view of the little trouble he had at the beginning of the congress, needed to be taken with a pinch of salt.

Archbishop Khrimian returned to Constantinople in deep despondency. Some weeks later he gave a sermon in the cathedral in which he painted a vivid picture of the Armenian claimants at Berlin. There, he said, the European diplomats had placed on the table a ‘dish of liberty’. The Bulgarians, Serbs and Montenegrins had taken their portions of the tasty harissa with their iron spoons; but the Armenians had only a paper spoon, which collapsed when they tried to partake.

Within a few years, as we shall see, Armenians had fashioned iron spoons for themselves, but the historic chance was past, and the dish of liberty, proferred to the Balkan people in 1878, was henceforward, like refreshment to Tantalus, held perpetually out of their reach.