History of The First Republic of Armenia 1918-1920, officially known as the Republic of Armenia

“The First Republic of Armenia was born under incredibly difficult conditions. For many, it represented not just survival, but the hope of a great new beginning. Armenian sovereignty was reborn on a small piece of our historic homeland—offering Armenians everywhere a place to call home, without fear of being Armenian.

I spent years working in various archives, reading through hundreds of books, reports, and documents—fields full of material. I uncovered many little-known pages of our history. Some I’ve written about in my book; others I’ve set aside… for now.”

— Dr. Smbat Minasyan

The Transcaucasian Federation Disintegrates

Despite this (Sardarabad’s) most significant victory for the Armenians, the political deterioration in Transcaucasia was so serious that there was no cause for rejoicing among Armenians.

At the Batum conference the Turks had seemed insatiable for territory. Khalil Bey’s new treaty had been a blow to all the delegates, except the Tatars. The Georgians, as much as the Armenians, were having their country devoured by the Turks; and seizing on the point that German and Turkish imperial ambitions diverged over the Caucasus, Georgia had sought the protection of Germany. Germany had been cultivating influence in Georgia before the war, and willingly gave her protection. She had no wish to give assistance to the Young Turks’ grandiose schemes for expansion to the east. Indeed, at this juncture, German generals were trying to persuade the Turks to send more troops south to the Arab provinces, threatened by the British advances.

On 24 May von Lossow failed in his attempt to mediate between Transcaucasia and Ottoman Turkey, and on that same day he reached a secret agreement with Georgia to grant her protection when she declared herself independent. Georgia’s move was a skilful one. Turkey would hardly dare to attack another ally of her senior partner (although on one brief occasion, this did indeed happen). The following day von Lossow sailed from Batum, with the documents necessary for the treaty, to arrive at Poti a day or so later, after Georgia had declared her independence.

With that splendid paradox of which the Georgians are such masters, their Menshevik ideals of a universal socialist brotherhood had emerged in practice as a desire to maintain their place in the sun, a somnolent colony comfortably supported by imperial Germany and doing as little fighting as possible.

Already, on 21 May, the Georgians had discussed independence and the future borders with the Azerbaijani Tatars, and neither party seriously thought that the Armenians had a chance against the Turks, so they were not even Discussed. On the day following the Georgians privately decided on independence, and on 26 May — at the moment that the Armenians were fighting with all their strength — Georgia declared her independence. With customary abuse against the other nations of Transcaucasia, Irakli Tsereteli dissolved the Seim, the Parliament of the state that had never really been. Georgian leaders then rushed to Poti, to meet von Lossow, and sign their first agreements with Germany.

The Azerbaijani Tatars followed suit on the 27th, establishing ‘eastern and southern Transcaucasia’ as the independent Republic of Azerbaijan.

The Armenians were dismayed by the Georgian proclamation. Their leaders were deeply divided on whether to declare independence, for many held the view that an independent Armenia would be at the mercy of Ottoman Turkey. Yet peace was vital; and since Georgia had quit the Transcaucasian Federation, the delegation at Batum (there since 11 May) had disintegrated. There was now no mechanism with which to make peace.

The Battle of Sardarabad

Only a small area of Armenian territory now remained unconquered by the Turks, and into that area hundreds of thousands of Armenian refugees had fled. It seemed only a matter of time before that too would be overrun.

By 22 May 1918 the Turks had captured Hamamlu (modern Spitak), half-way between Alexandropol and Karakilisa. Communications between Tiflis and Yerevan were now cut. Then, from Alexandropol, Turkish forces began a three-pronged attack, in an attempt to seize all that remained of Armenia. In this encounter, usually known as the battle of Sardarabad, Armenian forces finally hurled back the Turkish army and saved the eastern heartland of Armenia from the Turks.

The Turks attacked Nazarbekian at Karakilisa, and forced him back towards Dilijan. But there he stood firm. Around Yerevan itself the Armenian forces were commanded by General Silikian (Silikov). Two prongs of the Turkish advance were aimed directly at Yerevan. To halt their approach from Hamamlu, Silikian formed a thousand-strong force of riflemen, under the command of the Dashnak partisan leader Dro. This force held the Turkish advance at the defile of Bash Abaran. Just a little way west of Echmiadzin, the Armenian holy city, the third section of the Turkish advance was held, at Sardarabad. Indeed, the Armenians not only held them, they managed to throw the Turks back, until by the evening of May Silikian had forced them back 50 kilometers from Sardarabad, and a few days later Dro had driven them back towards Hamamlu.

In this time of supreme crisis for the Armenians they had halted the Turkish advance for the first time since the dismal evacuation of Erzindjan, and succeeded in throwing it back. Had they failed, it is perfectly possible that the word Armenia would have henceforth denoted only an antique geographical term (like Cappadocia). But despite being outnumbered by about two to one, and being deserted by their ‘colleagues’ in the Transcaucasian Federation (for the Georgians had obtained German protection, and the Tatars had no desire to hinder an advance of the Ottoman forces), they defeated the Turks in all three encounters.

Just as the Armenians had seized the initiative, and appeared able to force the Turks to retreat to Alexandropol and perhaps to Kars, Silikian received the order from Nazarbekian — ‘Cease fire’. A truce had been concluded in Batum. Silikian and his men were amazed and angry, since the Turks were running like rabbits; he was advised to disregard the order, declare himself dictator and continue the counter-attack. But he obeyed the order, notwithstanding, for which there were in fact pressing reasons, since ammunition was extremely low, and it was doubtful whether the Armenians could have reached Alexandropol before Turkish reinforcements had been brought up.

Armenia Declares Its Independence – First Republic of Armenia

On May 28th in 1918 the Armenian National Council (Tiflis) declares itself the supreme and sole administration of the Armenian provinces (made on 30 May, but with effect from the 28th).

The Armenian National Council, the body set up in Tiflis in October 1917, was by now acting as a government for the Armenian people of Transcaucasia; and realising that there was now no hope for Eastern Armenians but as an independent state, and that no peace could be signed at Batum by any body except an independent Armenia now that the Transcaucasian Federation was defunct, it prepared a declaration. Armenian members of the delegation at Batum were told they could negotiate a peace on behalf of an entity that might call itself ‘the Republic of Armenia’.

It was not until the evening of 29 May 1918 that a decision was finally made on the declaration of independence; only by then were the last doubters convinced. Armenia’s declaration of independence (made on 30 May, but with effect from the 28th) must be one of the most defensive of such documents ever written. It read:

In view of the dissolution of the political unity of Transcaucasia and the new situation created by the proclamation of the independence of Georgia and Azerbaijan, the Armenian National Council declares itself the supreme and only administration for the Armenian provinces. Due to certain grave circumstances, the National Council, deferring until the near future the formation of an Armenian national government, temporarily assumes all governmental functions, in order to pilot the political and administrative helm of the Armenian provinces.

No brave words about freedom or rights, no ‘cherished goal’ rhetoric — not even the phrase ‘Republic of Armenia’. Just a bare statement of the situation, from which one can sense the doubt, anguish and unwillingness that the Armenian leaders experienced. The Republic of Armenia, born amid the political collapse of Transcaucasia and taking its first breath of life on the battlefield of Sardarabad, could hardly be otherwise.

Independence had been thrust upon Armenia. Simon Vratsian had been an advocate of independence while others wavered; nevertheless in his history of the republic he likened Armenia’s declaration to the birth of a sick child. Certainly, in the circumstances of May 1918, the independence of Armenia was an occasion for sorrow rather than joy. Independence was declared because Transcaucasia had collapsed politically; as a ruined and desolate district of a once great city that has been bombed and cut off, local leaders assumed power in the dust-blown lots that survived. Yet that is only one way of looking at Armenia’s situation. Increasing autonomy was an ideal that Armenian political thinkers had been striving towards for half a century, as they struggled to rid their people of the imperial bureaucracies that encompassed them. They wanted to put the destiny of the Armenian people into Armenian hands. Even at this moment, as Armenia was still in danger of being swept away by a strong Turkish current, Armenian leaders were assuming the power to determine their people’s future. The compromises would have to be massive, but theirs would, henceforward, be the executive decision; and theirs too the responsibility. Armenia independent, even amid her war-broken misery and suffering, had entered a new category.

The Condition of the New Republic (in 1918)

The First Republic of Armenia born in very difficult and dangerous time for it. Almost all neighbor countries of the Republic of Armenia were in bad relation with it.

The land was rocky and scrubby, lacking cultivation or industry. The fields of Kars had been seized by the Turks, as had the industrial centre of Alexandropol. On the land which remained to the republic there were 300,000 Armenians, and another 300,000 hungry, penniless refugees; and a further 100,000 Tatars. The circumstances of the of the Armenian republic — war, chaos and disaster — could not have been less propitious.

The Armenian National Council, which had declared the independence of Armenia, now chose the new state’s first prime minister: Hovhannes Kachaznuni, a highly educated Dashnak thinker from Akhalkalak. This distinguished-looking figure was able, unlike others in his party, to compromise with non-Dashnak adventurism, dictatorship and managed democracy, blamed Dashnaktsutiun for the state of affairs, and refused to join.

It was the end of June — a month after the independence declaration — that Kachaznuni formed his five-man Cabinet; all Dashnaks, except for the non-partisan minister of war. Not until 19 July 1918 did the Cabinet reach Yerevan; only with difficulty, and regretfully, did Armenia’s leaders relinquish non-territorial politics. They must have seen the irony of the situation in which there were more Armenians in Tiflis, now the capital of Georgia, than in the backward district called the Republic of Armenia. In the seven-week absence of the official government, Dashnaktsutiun had shown its strength at dealing with situations at grass-roots level. In January 1918 Dro (Drastamat Kanayan) and Aram Manukian had establishes a tough ‘popular dictatorship’ in the Yerevan province, which was able to keep control and stave off disaster in the isolated, friendless republic.

A republic had to be constructed from virtually nothing. The tsarist autocracy had left almost nothing in Yerevan, no machinery of government that could be taken over and modified, as we are used to seeing in the new states of Africa and Asia today. All that the Armenian Government inherited were a few government offices and police cells. The country itself presented a Bosch-like of limitless suffering. Starving, stricken refugees, homeless, ragged and verminous, lurked in every sheltering spot. For none of the population was there anything but the smallest quantity of food; many dug for roots, and harvested the grasses of Yerevan. Death was the only constant in a world of many variables.

If the republic was to survive, diplomatic approaches had to be made to Constantinople and Berlin. So, in these last months of the was, Hamazasp (Hamo) Ohandjanian left for Berlin, and Avetis Aharonian set up a mission in the Turkish capital. Both went with begging bowls in hand; but their submission was short-lived, since the Central powers were disintegrating, and the war was drawing to a close.

The Batum Conference

Turkey and Transcaucasia met at Batum for peace talks on 11 May. The Transcaucasian delegation consisted of between 45 and 50 self-styled diplomats, an absurdly large figure, made necessary by the mutual suspicions of the members of different nationalities and factions within Transcaucasia.

Khalil Bey, minister of justice, led the Ottoman delegation. Vehib Pasha was beside him. Present too, at the request of their government, were three high-ranking Germans: General von Lossow, military attache in Constantinople, the fashionable and elegant sportsman Count von Schulenberg, former German vice-consul in Tiflis, whose pre-war hunting trips in western Transcaucasia were widely held to have been reconnoitring expeditions; and Otto von Wesendonck, adviser on Caucasian affairs. Their presence was a small indication that German and Turkish interests might not be identical.

Soon after the start of the conference Khalil made it clear that the Turkish side would no longer accept the treaty of Brest-Litovsk as a basis for negotiation. Stunned, the Transcaucasiants waited to see what he would demand instead. The most devastating aspects of his new draft treaty — for it was only to be a basis for discussion — were those that dealt with the new frontiers of Transcaucasia. The Armenian regions were all but wiped out. From the Yerevan province was taken the district of Surmalu (which contains the town of Igdir and the northern slopes of Mount Ararat) — a region which the Turks had only intermittently set foot in during past centuries — and all the territory up to and including the Kars-Julfa railway, including the city of Alexandropol. From the Tiflis province the districts of Akhalkalak and akhaltsikhe, the majority of whose population was Armenian, were lost.

The Transcaucasians searched for a diplomatic formula which would half the relentless emulation by the Young Turks of their imperial forbears. Chkhenkeli proposed mediation by the Central powers, hoping that Germany would curb Ottoman demands. Khalil rejected this: the treaty was a matter between Turkey and Transcaucasia only.

By 14 May no agreement had been reached on the new treaty, especially with regard to the railway. So late that night Khalil wrote to Chkhenkeli informing him that in view of the breakdown of the negotiations, the following morning he would begin troop movements in the direction of Julfa, along the Kars-Julfa railway. It was necessary for him (he said) to reach north Persia, to combat the British threat. But this was a smokescreen, since the British were still some way away. The real reason could be found in Enver’s relentless pan-Turkish fixation with Baku and Central Asia.

No message reached the front in time; and as General Nazarbekian was informed of the Turkish advance, it was occurring; soon the Turks were at the outskirts of Alexandropol. After a morning’s fierce fighting, enabling the civilians to evacuate. Nazarbekian gave the order to retreat. He moved his headquarters east yet again, to Karakilisa.

The Treaty of Batum

The first foreign political action of the infant republic ( mean’s Armenia) was to make peace with Turkey; the treaty of Batum was signed on 4 June 1918. The terms were humiliating for Armenia, but unavoidably so. As Germany dad held the pen at Brest-Litovsk, so now Turkey held it as Armenia signed. Again, it was territory that the Ottomans seized above anything else. All that was left to Armenia was the district of Nor Bayazid ( around Lake Sevan); parts of Sharur ( to the south), of Yerevan and Echmiadzin, and of Alexandropol were gone. The republic consisted of only 11000 land-locked square kilometers — about the size of Lebonan. Turkey had taken all of Surmalu and Nakhichevan, as well as the predominantly Armenian districts Akhalkalak and Akhaltsikhe. The only railway left to Armenia was about 50 kilometers of track in the north, and 6 kilometers extending west from Yerevan. But Turkey can use this railway for transporting his troops and ammunition to Azerbaijan

The Republic of Armenia Pitches into a New War

The Republic of Armenia was, in the meantime, appearing more like a normal state, not a mere patch of earth swarming with refuges, run by a dictatorship. The Populists agreed to take part in the government, and held four of the portfolios in Kachaznuni‘s new (4 November 1918) government.

However, no sooner was the Republic reasonably secure than it was involved in a tiresome and possibly avoidable war with Georgia. The origins of the conflict dated back to June 1918, when the Georgians, in order to forestall a Turkish advance on Tiflis, occupied the region of northern Lori which was about 75 per cent Armenian. Towns in the area included Sanahin, Alaverdi and Uzunlar. After the Mudros armistice, when the Turks were withdrawing from Transcaucasia, the Georgians indicated that they desired to take their place. Iraklii Tsereteli maintained, with that self-denying altruism for which the Georgians are so renowned, that the Armenians would after all be safer from the Turk as Georgian citizens. The Armenians were suspicious, and rejected a Georgian proposal of a quadripartite conference to solve the conflict. The participants were to have been the Mountaineer Republic of the North Caucasus, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. In December the Georgians, who had imposed a tsarist-style military bureaucracy upon the Armenian peasantry of the district, were confronted by a rebellion, centering chiefly upon the town of Uzunlar. Within days hostilities began between the two republics. The Dashnaks Seem to have been keen to prove that they could emulate the Georgians in their socialist imperialist aspirations, because the Armenian army, under Dro’s command, pushed north far beyond the regions with an Armenian majority, and came to within 50 kilometers of Tiflis. Fighting continued for a fortnight; by the end of it the Georgian army, which had initially fared disastrously, began to stage a come-back. This pointless, damaging, Gilbert-and-Sullivan escapade came to a conclusion on 31 December with a cease-fire arranged by the Allies, who had been aghast at the petty squabble they had been witnessing.

The war was inconclusive for both sides. But the real damage was that in the eyes of the world; here were two states, that had been born amid the fire and ice of the last four years, which had suffered deprivation and fearful onslaught, but which were now, while the rest of the the world was healing its wounds and longing for peace, laying into one another like two hostile cats. Supporters of the Armenians, who had regarded the people they championed as a blameless, eternally suffering nation, received a rude shock. They appeared to be rather like everybody else.

Weather Conditions

The winter of 1918-1919 was the most severe in memory in Armenia. For the republic, painfully constructing itself, this was a very serious setback. Just under 20 per cent of the country’s population was wiped out. Villages were desolated. The situation for the 300.000 Turkish Armenian refugees, lacking shelter or food, was catastrophic. Even the settled population of Armenia hovered on the edge of starvation, since the supplies which in former times would have reached Armenia from north of the Caucasus were now cut off by the Russian civil war. Appalled relief workers sent harrowing descriptions to Europe and the United States, and the phrase ‘Starving Armenians’ gained widespread and justified currency. It elicited genuine compassion from Europeans and especially Americans. Large shipments of food and clothing were sent to the suffering country.

For those Turkish Armenians who struggled to return home after the cruelties of the deportations the situation was ferociously bleak, and the utter lack of help that they received highlights again the distinction between the words and deeds of those powers with the power to be of assistance.

The Turks seemed not to consider that the war had ended, or that their government had signed an instrument of defeat. The Times (London) reported on 4 January 1919 that atrocities were continuing, homes were being wrecked and all available goods were being carried away by the Turks. The same paper described on 16 January how the deported Armenians were struggling to return home: ‘Few have any transport, and they are making long journeys on foot from the Mesopotamian deserts to the snow-bound districts in the north, barefooted, half-clad, hungry, sick, and exhausted.’ Within Ottoman Turkey itself, the Allied occupation extended no further east than Konya, and all Armenians were still terrified of further massacre. The Times Summed up the situation in a leading article of 2 May 1919:

The Turkish soldiery, disbanded but not disarmed, it still wandering about the more inaccessible districts of Armenia. Famine has follow massacre, and with it, as so often, has come typhus and other diseases. Since the armistice the Armenians have been sustained by political hopes, soon destined, we hope, to be fulfilled; but a nation cannot live on politics alone, and the appeal now made is for the elementary needs of basic sustenance.

The Paris Peace Conference

When the peace conference convened in Paris in January 1919, nearly all the participants foresaw that provision would be made for an independent Armenian state to be established within secure boundaries — at last the ‘great powers’ would be able to make amends for the murder and devastation that their policies had inflicted on Armenia for the past 40 years. But this was not to be; indeed, the suffering and wretchedness of Armenians — the pitiful, starving hopelessness — was worse in the years following the war than at any time except during the Ittihadist organized mass murder of 1915-1916. Nothing that the statesmen said or did at Paris made any difference to Armenia; their weighty and wordy declarations appear, when one reads them, as utterances designed to give the speaker an aura of satisfies charitable well-being. For all the good they did Armenians they might as well have been random nonsense syllables. Hence the peace conference need not detain us for long.

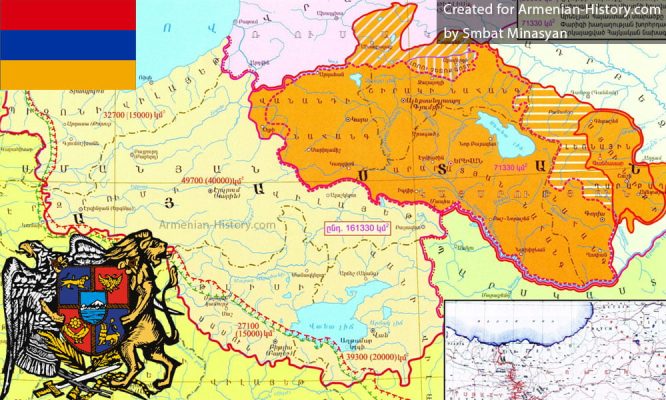

Encouraged by Allied declarations and assurances, the Armenians staked out large claims at Paris. Already there was Boghos Nubar, as head of the Armenian national delegation. But in February 1919 a delegation arrived representing the Republic of Armenia, headed by author and poet Avetis Aharonian (Foreign minister of the Republic of Armenia). Nubar and Aharonian were widely dissimilar in background and outlook; Nubar with his origins in a wealthy Levantine minority, at ease among the statesmen of Paris, intensely conservative by nature; Aharonian, a man of ironical wit, as rugged as the Caucasian scenery that had given him birth; Nubar with unlimited faith in the ‘civilised’ west, Aharonian more sceptical, believing — as would anyone who had been close to the turmoil of the birth of independent Armenia — that the people’s own strength on the ground is more valuable than the guarantee of a foreign statesman. Nevertheless the two agreed to merge their delegations into the ‘All-Armenian Delegation’, and to agree on all major issues. They presented their joint memorandum to the peace conference in February 1919. Reviewing past Ottoman oppression, and the enormous losses that the Armenian people had sustained during the war, they now claimed their independence. Their state was to include the ‘six vilayets’ of Turkish Armenia (Van, Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Kharput, Sivas and Erzerum), excluding a few marginal non-Armenian districts; also the province of Trebizond, to give access to the sea. It should also include the Republic of Armenia as it was then constituted, plus Mountainous Karabagh to the east, Zangezur to the south, and to the north some Armenian-inhabited lands which it claimed from Georgia. But that was not all. Armenia also claimed the four districts of Cilician Armenia, on the Mediterranean coast, where there was quite a large Armenian population dating from the period of the medieval kingdom. Armenia would have been a gigantic country; yet the proposal differed only in some small particulars from the British and American proposals then current. In this huge country Armenians would only be a small minority; but the Armenians insisted on including in their demographic estimates with some justification all those Armenians murdered as a result of the Turkish government’s policies of 1915-1916. Not to have done so would be to acquiesce in the Turks’ government-sponsored genocide. This argument was also trenchantly put by Sir Eyre Crowe, a member of the British delegation in Paris. He wrote to a London colleague on 1 December 1919: ‘To consider and decide the Armenian question purely on the basis of present numbers would surely amount to countenancing and encouraging the past Turkish method of dealing with the problem of their subject nationalities!’ Nevertheless, throughout 1919 and 1920 the Turks and their supporters naively laid claim to Armenian lands, on the grounds that there were no Armenians living in the areas, feigning ignorance of the policies of 1915-1916. In their submission, the Armenians requested general protection for 20 years either from the Allies or the League of Nations, and the direct guidance of one specific mandatary.

In response to this and every other request or appeal addressed to them the Allies did nothing. Despite their grandiose public statements, and despite the closeness at this date of Armenian bids to British and American policy outlines, nothing was done to secure a lasting Armenia out of the wreckage and disaster of the war. The Allies would not even recognize the Republic of Armenia, so keen were they to pursue their vendetta with the Bolsheviks, and so fearful of upsetting Russian ‘democrats’, who would demand the incorporation of Armenia into a reconstituted Russia. Their immobility in the face of continuous reports of Armenian wretchedness, starvation and death was as icy as their inaction during Abdul Hamid’s persecutions. And here there was a further twist of fate. No decision was reached. At least the Berlin congress, for all its haughty imperialism, had been over in a month; but after 1918 it took, as we shall see, four and a half years for the wise statesman to sort out a treaty that would stick. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the great powers were if anything more greedy, jealous and self-interested than formerly. The only action that they did sponsor was so foolish, short-sighted and ill-conceived that it proved, in its implications, disastrous to the non-Turkish peoples of east and west Anatolia, and to the designs of the powers themselves. That was the Greek occupation of Smyrna (Izmir), 15 May 1919.

Allied Conferences in London and San Remo

It was in these circumstances that Britain and France convened the first London Conference, with the aim of working out a treaty with Turkey (December 1919 – March 1920). Plans more realistic for the future size of Armenia prevailed now than those put forward in Paris February 1919. The idea of a Greater Armenia from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean had been scrapped, even if largely because it conflicted with French territorial aspirations for a ‘mandate’ area embracing Cilicia and stretching north-eastwards as far as Kharput and Diyarbekir. Both Britain and France realized that any areas of Turkish Armenia that would become Armenian state would now encompass parts of the provinces of Bitlis, Van, Erzerum and (to enable Armenia to have a coastline) Trebizond; this was the recommendation of an Allied Commission in its report of March 1920.

But what to do with Turkish Armenia once its size had been decided? A mandate was essential; in contrast to Allied propaganda and pretensions in the Arab world, where blatant colonialism was half hidden under the unconvincing fig-lead of ‘bringing the peoples up to a level of civilization’, Armenia, ruined by massacres and heavy warfare during the world war, and now starving, really needed the assistance of a stronger power. Yet each power in turn said apologetically that it could not take the mandate for Armenia. At the London Conference the powers agreed to ask the League of Nations to accept the mandate.

The League considered the matter on 9-11 April. In its report it pointed out that it was not a state, and had no army and no finances. It could not accept and exercise a mandate; only give a right to supervise one. A power had to be found.

Still hoping that America would, somehow, accept the mandate, the Supreme Council of the League (Britain, France, Italy and Japan) met in San Remo (18-26 April) to try to bring their deliberations about the former Turkish empire to a conclusion. There is a pathetic triviality about the proceedings, as far as they related to Armenia, Occurring as they did on the very eve of Bolshevik coup in Azerbaijan, which tightened further the hold of the anti-Entente forces in the Caucasus. As if they were playing an elaborate and formal game of croquet, the world leaders spent nearly all the brief time they allotted themselves to discuss Armenia scoring off one another over the matter of whether or not the city of Erzerum should be included in the proposed Armenia. Like players in the game making careful strokes merely to send their opponents flying from the hoops, so our modern Atlases marshalled their arguments about Erzerum — Lloyd George and Signor Nitti against its inclusion in Armenia, Lord Curzon and M. Berthelot in favour. Since none of them intended actually to do anything on the ground to help this Armenia come into existence the exercise was of tedious aridity — without even a suggestion of the excitement afforded by a real game of croquet.

The upshot of the deliberations at San Remo was that the leaders decided once more to appeal to President wilson to accept the mandate, or, failing that, to fix boundaries of the state. But when the president proposed the acceptance of the mandate to Congress on 24 May, the Senate, after four days’ discussion, voted by 52 to 23 to decline to take it on. So the president was left to draw the map of an Armenia which seemed unlikely to come into existence at all; his stroke through the next hoop. Meanwhile on 11 May Britain and France handed to Turkish representatives from the puny puppet government in Constantinople the text of the treaty with which they intended to wind up the affairs to Turkey and solve the Eastern Question, the treaty to be known as the treaty of Sevres, perhaps the most elegant and pointless all the shots in the game.

Books Related to this topic։ First Republic of Armenia 1918-1920

Հայերը Հյուսիսային Կովկասում – 1918-1920 ԹԹ.

You can also check Armenian-History.com Facebook Page