Introduction: A Century of Transformation and Turmoil

The 4th century stands as one of the most decisive and dramatic periods in Armenian history. It was an era that began with the monumental conversion of Armenia to Christianity under King Trdat III in 301 A.D., making Armenia the first nation in the world to adopt Christianity as its state religion. Yet, it was also a century marked by political instability, noble rivalries, foreign invasions, and religious struggles.

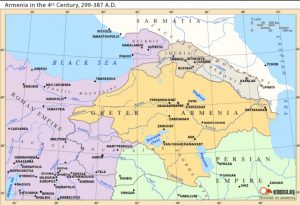

Following the death of Trdat III, Armenia endured almost a hundred years of fluctuating fortunes. Kings rose and fell—some remembered for their valor and vision, others for their failings and betrayals. The kingdom was caught in the geopolitical rivalry between the Byzantine Empire and the Sasanian Persian Empire, both eager to exert influence over the strategically vital Armenian plateau.

This period ultimately witnessed the First Division of Armenia in 384–387, when the kingdom was partitioned between Byzantium and Persia. The larger eastern portion, known as Persarmenia, fell under Sasanian rule, while the Romans retained control of Sophene and Lesser Armenia. This division marked the beginning of a new era and the end of Armenia’s centuries-old political unity under the Arshakuni kings. By Smbat Minasyan

Reign of King Trdat III (Tiridates III) and the Birth of Christian Armenia

The reign of King Trdat III, though ending tragically, was monumental in shaping Armenian identity. Under his leadership—and with the guidance of Saint Gregory the Illuminator—Christianity was formally proclaimed as the state religion in 301 A.D. This spiritual transformation not only aligned Armenia with the Christian Byzantine Empire but also created lasting cultural, literary, and moral foundations for the Armenian people.

However, Trdat’s later years were marred by internal unrest. Feudal lords who had not fully embraced the Christian faith conspired against him. Retiring to his beloved region of Yegeghyats, he narrowly survived an assassination attempt before falling victim to poison administered by his own chamberlain. His death in 331 opened the door to a century of succession crises.

Khosrov II (331–339) – Defender of the Realm

Khosrov II, the son of Trdat III, inherited a kingdom under threat from the Sasanian Persians. He proved to be both patriotic and constructive, fostering prosperity despite the looming danger from King Shapur II of Persia.

With the courage of General Vatche Mamigonian, Armenian forces repelled several Persian incursions. Khosrov also quelled a rebellion by pagan nobles who opposed Christianity, personally punishing the conspirators and ordering the construction of the new city of Dvin—later a significant cultural and political center. His reign, though not without challenges, brought relative stability until his death in 339.

Diran (339–350) – A Troubled Reign

Khosrov II was succeeded by his son Diran, whose reign was marked by poor judgment and strained relations with the Church. His attempt to honor the paganizing Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate within Armenian churches provoked the Patriarch Houssig, whom Diran had executed. He also ordered the massacre of members of the Resdouni and Manavazian noble houses.

Diran’s inconsistent foreign policy toward Persia led to his downfall. Betrayed and taken captive to Persia, he was blinded by Shapur II, leaving Armenia vulnerable to foreign influence.

Arshag II (350–367) – The Centralizer

Diran’s son, Arshag II, sought to unify Armenia’s fractured nobility under a strong central authority. He founded the city of Arshagavan as a refuge for politically persecuted individuals, but this move angered the powerful nakharars (noble families), leading to its destruction.

Arshag appointed the capable Mamigonian family to lead the kingdom’s defense and oversaw the appointment of Nerses the Parth as Catholicos of Armenia. Nerses proved to be a visionary church leader, establishing schools, orphanages, and hospitals.

However, Arshag’s attempt to align with Byzantium drew Persia’s wrath. Betrayed by Armenian ministers Merujan Arzrouni and Vahan Mamigonian, he was lured to Persia under false pretenses and imprisoned in the Anhoush fortress. There, surrounded by the grim reminder of his slain commander Vassak Mamigonian, he took his own life.

Regency of Queen Paranzem and the Heroic Resistance

Following Arshag’s death, his young son Bab was sent to the Byzantine court for safety. His mother, Queen Paranzem, assumed leadership, rallying the people in resistance against Persia. The fortress of Artagers became the center of Armenian defense.

Despite betrayal by two ministers, Paranzem’s determination inspired them to rejoin the national cause. In a daring night attack, Armenian forces routed the Persian camp. Enraged, Shapur II besieged Artagers for a year, leading to famine and eventual surrender. Paranzem died a martyr’s death, crucified for her defiance.

King Bab (367–374) – The Controversial Monarch

Bab’s return to Armenia was marred by political missteps. His execution of two loyal ministers to appease Persia alienated many. He clashed with the Church, closing charitable institutions founded by Catholicos Nerses and asserting royal control over religious matters.

Still, he personally visited his subjects and sought to remove Roman influence from Armenia. His life ended in treachery when he was assassinated at a banquet by Roman commander Trajanus.

Varazdat and General Manuel Mamigonian

Bab was succeeded by his cousin Varazdat, a physically imposing but politically naïve ruler. Influenced by deceitful advisors, he ordered the execution of the heroic general Moushegh Mamigonian.

The real stabilizer of this period was Manuel Mamigonian, Moushegh’s son, who became commander-in-chief. Under his leadership, Armenia enjoyed renewed prosperity, the reopening of educational and charitable institutions, and victories against Persia. His loyalty to Byzantium secured temporary peace.

Division of Armenia – 384–387: The First Partition

Manuel’s death ushered in new instability. King Arshag III briefly reigned before being replaced by Khosrov IV, who tried to renew ties with Byzantium. Accused of disloyalty to Persia, he was imprisoned, and Vramshapuh (382–414) ascended the throne.

During Vramshapuh’s reign, a defining moment in Armenian culture occurred: Mesrop Mashtots, with the support of Catholicos Sahak Partev and the king, created the Armenian alphabet in 405 A.D. This innovation enabled the translation of the Bible into Armenian, a masterpiece known as the “Queen of Translations.”

Politically, however, Armenia’s independence was waning. In 384–387, the kingdom was divided for the first time between the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. The larger eastern portion, Persarmenia, came under Persian rule, while Byzantium retained Sophene and a small portion of Lesser Armenia. This partition marked the beginning of centuries of divided Armenian sovereignty.

Shapur (416–420) and the Persian Exarchate (420–423)

Following Vramshapuh’s death, the throne passed to Shapur, a pro-Persian figure whose short reign reflected the growing dominance of Sasanian influence in Armenia. His governance further eroded Armenian autonomy.

By 420, direct Persian control was established through the appointment of a marzpan (governor) during a brief exarchate that lasted until 423. This arrangement underscored the weakening position of the Arshakuni kings and the encroaching authority of Persia in Armenian affairs.

Ardashes III (423–428) – The Last Arshakuni King

The final ruler of the dynasty, Ardashes III, was a weak-minded and ineffectual monarch. His inability to govern effectively alienated both the nobility and the Church. Catholicos Sahak Partev, despite recognizing Ardashes’ shortcomings, urged patience and unity, famously warning that “a national weak sheep is preferable to a foreign, healthy, but ferocious beast.”

However, court intrigue proved stronger than loyalty. Ministers, discontent with Ardashes’ leadership, appealed to the Persian king Vram, accusing both the king and the Catholicos of incompetence. Summoned to Persia, they were both deposed, marking the end of the Arshakuni (Arsacid) Dynasty in Armenia.

Cultural Legacy of the 4th Century

Despite political instability and the eventual fall of the Arshakuni dynasty, the 4th century left a legacy that would endure for centuries. The official adoption of Christianity in 301 A.D., the creation of the Armenian alphabet in 405 A.D., and the “Queen of Translations” Bible transformed Armenian spiritual and intellectual life.

Even as foreign domination deepened after the First Division of Armenia (384–387), the cultural foundations laid during this century became a cornerstone of Armenian identity. Literature, ecclesiastical tradition, and education flourished, ensuring that the Armenian nation preserved its heritage under Byzantine and Persian rule.