DATE & PLACE OF BIRTH:

April 26, 1968, Yerevan, Armenia

EDUCATION:

1975-1985 Eghishe Charents High School (No. 67) with English bias, Yerevan

1985-1990 Yerevan State University, Department of History, MA, 1990

Speciality: Universal History, Social Sciences

1991-1995 Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan, Ph.D.

(Doctor of History), 1995

Speciality: Armenian History, Diaspora and American Ethnic Studies

1997-1998 American University of Armenia, Intensive English Program, Yerevan

1998 American University of Armenia, Graduate School of Political Science & International Affairs, Yerevan

ACADEMIC AWARDS AND HONORS:

1981, 1982, 1983, 1984 Testimonials of the Ministry of Education of the Armenian SSR for Excellent Successes and Exemplary Behavior, on the occasion of Graduating from VI, VII, VIII, IX classes at Eghishe Charents High School (No. 67) with English bias, Yerevan

1985 Honorary Certificate from the Board of Directors of Eghishe Charents High School (No. 67) for Excellent Indices in Elementary Military Training, Personal Discipline and Active Public Work, Yerevan

1985 Gold Medal for Excellent Study and Behavior from Eghishe Charents High School (No. 67) with English bias, Yerevan

2000 Certificate from the Institute of Oriental Studies, National Academy of Sciences for having reported at the XXI Conference of Young Orientalists of Armenia (June 1-2), Yerevan

2001 Certificate: The National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia and the Galoust Gulbenkian Foundation award to Knarik Avakian the title “The Best Young Scientist of 2001” for her Outstanding Research Achievements, Yerevan

2002 Certificate of Successful Completion of “Elements and Applications of Web Design” Training (May 6-17), organized by the Public Affairs Section of the US Embassy, Armenia, Yerevan

AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION:

Armenian-American Ethnic and Community Studies

Armenian Diaspora Studies

History of Armenia and the United States of America

History of the Armenian Protestant Church

Universal History

Social Sciences

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE:

1990-1992 Teacher of History at High School (No. 39), Yerevan

1992-1994 Assistant of Professor of History at Gladzor University, Yerevan

1995-1997 Junior Researcher at the Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan

1998-2001 Senior Editor at the Armenian Encyclopedia, Yerevan

1998-Present Senior Researcher at the Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan

ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES:

1997-Present Head of the Young Scientists’ Council, Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan

1998-Present Member of the Young Scientists’ All-Academic Council, National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan

1999-Present Member of the Academic Council of the Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan

COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES:

1990s Participation in organizing Local, National Assembly & Presidential elections, Yerevan 1997-Present Participation to the activities of Graduate Women’s Association, Yerevan

PUBLICATIONS:Book:

“The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924).” Hayastani Hanrapetutian Gitutiunneri Azgain Akademiayi “Gitutiun” Hratarakchutiun (“Science” Publishing House of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia). Dedicated to the 180th and the 80th Anniversaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1819) and of the Near East Relief (1919). Yerevan, 2000, 240 pages (in Armenian, with English & Russian Summaries).

Scientific Articles:

Armenians During the Colonial Period of America. Banber Yerevani Hamalsarani. Hasarakakan Gitutiunner (Yerevan University Herald. Humanitarian Sciences). Yerevan, 1994, No. 2 (83), pp. 129-133 [reprinted in Ararat, Beirut] (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). Thesis. Yerevan, 1995, 21 pages (in Armenian, with English & Russian Summaries).

Participation of the Armenian-Americans to the World War II. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutiunneri. HH GAA Handes (Herald of Humanitarian Sciences. Journal of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 1995, No. 1 (589), pp. 176-188 [reprinted in Ararat, Beirut] (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

Distribution and Social-Economic Condition of Armenians in the United States of America (1834-1924). Banber Yerevani Hamalsarani. Hasarakakan Gitutiunner (Yerevan University Herald. Humanitarian Sciences). Yerevan, 1995, No. 1 (85), pp. 54-66 [reprinted in Ararat, Beirut, and Lraber Stanbuli Hayots Patriarkutean (Herald of Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul), Istanbul] (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

Armenian Spiritual, Educational and Cultural Life in the United States of America (1888-1924). Banber Yerevani Hamalsarani. Hasarakakan Gitutiunner (Yerevan University Herald. Humanitarian Sciences). Yerevan, 1995, No. 3 (87), pp. 189-196 [reprinted in Ararat Yearbook, Beirut, and Lraber Stanbuli Hayots Patriarkutean (Herald of Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul), Istanbul] (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

The Emigration of the Armenians to the United States of America (1834-1924). Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutiunneri. HH GAA Handes (Herald of Humanitarian Sciences. Journal of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 1996, No. 1 (591), pp. 92-101 [reprinted in Ararat, Beirut] (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

Public-Political Life of the Armenians in the United States of America (1886-1924). Banber Yerevani Hamalsarani. Hasarakakan Gitutiunner (Yerevan University Herald. Humanitarian Sciences). Yerevan, 1996, No. 3 (90), pp. 174-185 (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

From the History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America. Bnorran. Handes Hayastani Hayrenaktsakan Miutiunneri Khorhrdi (Cradle. Journal of the Council of the Compatriotic Unions of Armenia). Yerevan, 1997, No. 2 (6), pp. 23-27 (in Armenian).

Armenians of Turkey During the Colonial Period of America. Lraber Stanbuli Hayots Patriarkutean (Herald of Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul). Istanbul, 1997, September 16, No. II/18 (51), pp. 24-26 (in Armenian).

The Emigration of the Armenians of Turkey to the United States of America (1834-1894). (a). Lraber Stanbuli Hayots Patriarkutean (Herald of Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul). Istanbul, 1997, December 3, No. II/22 (55), pp. 15-16 (in Armenian) (to be continued).

The Emigration of the Armenians of Turkey to the United States of America (1834-1894). (b). Lraber Bolsahay Patriarkutean (Herald of Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul). Istanbul, 1997, December 10, No. II/23 (56), pp. 12-14 (in Armenian) (to be continued).

The Exodus of the Armenians to the United States of America (1618-1924). Baikar. Ramgavar-Azatakan Gitatesakan, Hasarakakan, Kaghakakan, Mshakutayin Amsagir (Struggle. Democratic-Liberal Scientificotheoretical, Public, Political, Cultural Journal). Yerevan, 1998, No. 1, pp. 26-30 (in Armenian).

Henry Morgenthau and the Armenian-Americans. Henry Morgenthaun ev Hay Zhoghovurde (Henry Morgenthau and the Armenian People). Yerevan, 1999, pp. 38-49 (in Armenian).

Some Documents of Archive of the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey Concerning the Armenian Community of the United States of America. Banber Yerevani Hamalsarani. Hasarakakan Gitutiunner (Yerevan University Herald. Humanitarian Sciences). Yerevan, 1999, No. 2 (98), pp. 126-138 (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

The Exodus of the Armenians to the United States of America. Droshak. Pashtonatert Hay Yeghapokhakan Dashnaktsutean (Banner. Official Magazine of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation). Yerevan, 1999, December, 30th (63rd) Year, No. 18 (1562), pp. 55-58 [to be printed in Haykakan Spiurk Hanragitaran (Encyclopedia of Armenian Diaspora). Yerevan] (in Armenian).

Henry Morgenthau and the Armenians. Armenian Mind. Journal of the Armenian Philosophical Academy (Hay Mitk. Hayots Pilisopayakan Akademiayi Handes). Yerevan, 2000, Vol. IV, No. 2, pp. 257-276 [to be printed in Nationalities Papers. New York (23 pages)] (in English).

The Archival Documents of the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey Concerning the Armenian Community of the USA (End of the XIX – Beginning of the XX Centuries). Merdzavor ev Midjin Arevelki Erkrner ev Zhoghovurdner (The Countries and Peoples of the Near and Middle East). Yerevan, 2000, Vol. XIX, pp. 7-15 (in Armenian, with English Summary).

The Documents of Archive of the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey Concerning the Armenian Emigrants of the USA (End of the 19th Century – Beginning of the 20th Century). Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutiunneri. HH GAA Handes (Herald of Humanitarian Sciences. Journal of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 2000, No. 2 (602), pp. 211-220 (in Armenian).

The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). Avetaber Verelk. Kronakan, Azgayin, Mshakutayin Parberatert Sb. Gregory Hay Katolik Ekeghetsu (Precursor Ascent. Religious, Spiritual, Cultural Periodical of St. Gregory Armenian Catholic Church). Glendale, 2001, No. 1, pp. 35-38 (in English).

The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). Navasart Amsagir. Grakan, Mshakutayin, Azgayin Amsagir (Navasart Monthly. Literary, Cultural, National Monthly). Glendale, 2001, Vol. XIXI, Second Quarter, No. 221-222, pp. 30-32 (in Armenian).

The Emigration of the Armenians to the America (1834-1924). Surp Prgich. Amsatert Surp Prgich Hayots Hivandanotsi (Saint Savior. Monthly of the Saint Savior Armenian Hospital). Istanbul, 2001, Year 51, April, No. 618, pp. 38-44 (in Armenian).

Burdensome Labor Conditions for the First Armenians Emigrated to the America. Surp Prgich. Amsatert Surp Prgich Hayots Hivandanotsi (Saint Savior. Monthly of the Saint Savior Armenian Hospital). Istanbul, 2001, Year 51, June-July, No. 620-621, pp. 37-40 (in Armenian).

The Emigration of the Armenians to the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). Eritasard Gitashkhatoghneri Hodvadsneri Zhoghovadsu. HH GAA Handes (Collection of Articles of the Young Researchers. Journal of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 2001, No. 1 (2), pp. 152-156 (in Armenian, with Armenian, English & Russian Summaries).

The Armenian-American Periodicals and Printing Houses (1888-First Half of the 1920s). Handes Hayagitutian. Erevani Kh. Aboviani Anvan Haykakan Petakan Mankavarzhakan Hamalsarani Gitakan Hodvadsneri ev Hraparakumneri Zhoghovadsu (Journal of Armenology. Collection of Scientific Articles and Publications of Yerevan Kh. Abovian Armenian State Pedagogical University). Yerevan, 2001, No. IV, pp. 83-86 (in Armenian, with Russian Summary).

From the History of the Armenian-American Compatriotic Unions (End of the 19th Century – Beginning of the 20th Century). Droshak. Pashtonatert Hay Yeghapokhakan Dashnaktsutean (Banner. Official Magazine of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation). Yerevan, 2002, January, 33rd (66th) Year, No. 1 (1573), pp. 151-160 (in Armenian).

From the History of the Armenian-American Compatriotic Unions. Bnorran. Handes Hayastani Hayrenaktsakan Miutiunneri Khorhrdi (Cradle. Journal of the Council of the Compatriotic Unions of Armenia). Yerevan, 2001, No. 1-2 (), pp. (in Armenian) (in progress).

The Armenian-Americans During the Years of the Armenian Genocide. Hayots Tseghaspanutian Patmutian ev Patmagrutian Hartser. Gitakan Ashkhatutiunner (Cases on the History and Historiography of the Armenian Genocide. Scientific Researches). Yerevan, 2001, No. , pp. (in Armenian, with English & Russian Summaries) (in progress).

Armenian Educational and Research Institutions of the United States of America (From the Beginning to Our Times). Haykakan Spiurk Hanragitaran (Encyclopedia of Armenian Diaspora). Yerevan (in Armenian) (in progress).

Evangelizm in the Armenian Reality. Banber. Pashtonatert Fransahay Avetaranakan Miutean ([Panpere. Revue Mensuelle Evangelique]. Herald. Review of the Armenian Evangelical Union of France). Marseilles (in Armenian) (in progress).

Magazine Articles:

The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). Hayastani Hanrapetutiun. Oratert (Republic of Armenia. Daily). Yerevan, 1996, August 28, No. 169 (1608), p. 2 (in Armenian).

The First Armenians in America. Gitutiun. HH GAA Erkshabatatert (Science. Semi-Monthly of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 1996, November 16-30, No. 20 (84), pp. 2, 4 (in Armenian).

On the Case of the Article “Pennsylvania.” Gitutiun. HH GAA Erkshabatatert (Science. Semi-Monthly of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 1997, January 1-15, No. 1 (87), p. 2 (in Armenian).

The Community Values are Higher than Personal Ambitions. (a). – “Marmara” is Making Dissolution. Jamanak. Kaghakakan, Zhoghovrdakan Oratert (Time. Political, Popular Daily). Istanbul, 1997, September 5, No. 6091, p. 2 (in Armenian) (to be continued).

The Community Values are Higher than Personal Ambitions. (b). – Armenian Church is Not Being Built Everyday. Jamanak. Kaghakakan, Zhoghovrdakan Oratert (Time. Political, Popular Daily). Istanbul, 1997, September 6, No. 6092, p. 2 (in Armenian) (to be continued).

The Community Values are Higher than Personal Ambitions. (c). – The Patriarchate is Sacred. Jamanak. Kaghakakan, Zhoghovrdakan Oratert (Time. Political, Popular Daily). Istanbul, 1997, September 8, No. 6093, p. 2 (in Armenian).

The Armenian-American Apostolic Church and the 100 Years Old Diocese. Hayastani Hanrapetutiun. Oratert (Republic of Armenia. Daily). Yerevan, 1998, May 19, No. 96 (2053), p. 5 (in Armenian).

The Armenian Evangelical Church and the 80 Years Old Missionary Association. Hayastani Hanrapetutiun. Oratert (Republic of Armenia. Daily). Yerevan, 1998, July 11, No. 135 (2092), p. 5 (in Armenian).

Evangelizm in the Armenian Reality. Hayastani Hanrapetutiun. Oratert (Republic of Armenia. Daily). Yerevan, 1998, September 9, No. 177 (2134), p. 7 (in Armenian).

The Humanist: Henry Morgenthau. Azg. Oratert (Nation. Daily). Yerevan, 1999, April 21, No. 71 (1816), p. 4 (in Armenian).

The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). Nakhijevan. “Nakhijevan” Hayrenaktsakan Miutean Pashtonatert (Nakhijevan. Newspaper of “Nakhijevan” Compatriotic Union). Yerevan, 2000, B Year, June-July, No. 15, p. 16 (in Armenian).

The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). Nayiri. Erkshabatatert (Nairi. Semi-Monthly). Beirut, 2000, F Year, September 5, No. 132, pp. 8-9 (in Armenian).

225 Years Old Independence of the United States of America and the Armenian-Americans. Azg. Oratert (Nation. Daily). Yerevan, 2001, July 4, No. 123 (2327), p. 5 (in Armenian).

The Armenian Community of the USA. From the Beginning to 1924. Golos Armenii. Obshchestvenno-Politicheskaia Gazeta (Voice of Armenia. Social-Political Newspaper). Yerevan, 2001, July 5, No. 72 (18724), p. 5 (in Russian).

PAPERS PRESENTED AT PROFESSIONAL MEETINGS:

23rd Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, November 23-24, 1992. Participation of the Armenian-Americans to the World War II. (Abstracts: pp. 28-29) (in Armenian).

24th Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, November 2-3, 1993. The Emigration of the Armenians to the United States of America (Beginning of the 17th Century-1920) (in Armenian).

Economic Education and Policy Analysis During a Time of National Transition. International Conference. Institute of International Economic Relations and Control. Yerevan, June 19-22, 1995. Emigration of the Armenians to the United States of America (1618-1924). (Abstracts: p. 24) (in English).

25th Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, May 12-13, 1997. The Exodus of the Armenians to the United States of America (1618-1924). (Abstracts: pp. 9-10) (in Armenian).

Armenian Historical and Cultural Issues. Conference. State Museum of History of Armenia. Dedicated to the Memory of Alex Manugian, the Great Philanthropist and Supporter of Armenology, National Hero of Armenia. Yerevan, October 15-16, 1997. The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). (Abstracts: pp. 30-31) (in Armenian).

Diaspora Structures. Conference. Student’s Scientific Society of the Philological Department of the Yerevan State University. Dedicated to the 50th Anniversary of Establishment of the Student’s Scientific Society of the Yerevan State University. Yerevan, December 12, 1997. The Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) (in Armenian).

Christianity and the Armenian Reality. Conference. “Hayk” Foundation, Artsakh and Aragadsotn Dioceses of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Dedicated to the 1700th Anniversary of the Proclamation of Christianity in Armenia. Yerevan, Oshakan, Gandzasar, November 12-15, 1998. Evangelizm in the Armenian Reality. (Abstracts: pp. 12-13) (in Armenian).

The Armenian Genocide. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau and the American Responses (1914-1923). International Conference.Henry Morgenthau and the Armenian-Americans (in English & in Armenian). National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia (NAS) (Yerevan), Armenian National Institute (ANI) (Washington). Dedicated to the Memory of Henry Morgenthau, the American Diplomat, Friend of the Armenian People. Yerevan, April 22, 1999.

26th Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, June 29-30, 1999. The Documents of Archive of the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey Concerning the Condition of the Armenian Emigrants of the USA (End of the 19th Century – Beginning of the 20th Century). (Abstracts: pp. 16-17) (in Armenian).

The Armenian National Culture. Republican Conference. No. X. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Dedicated to the 40th Anniversary of Establishment of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, NAS RA. Yerevan, November 30 – December 2, 1999. Formation of the Armenian-Americans’ Nation-Preserving Basis. (Abstracts: pp. 7-9) (in Armenian).

The 21st Century without Genocides. Conference. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, Museum-Institute of the Armenian Genocide, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, Foundation of the Armenian Cases, Munich. Dedicated to the 85th Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide (1915-2000). Yerevan, April 18-21, 2000. The Armenian-Americans During the Years of the Armenian Genocide (in Armenian).

XXI Republican Conference of Young Orientalists of Armenia. Institute of Oriental Studies, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, June 1-2, 2000. The Archival Documents of the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey Concerning the Armenian Community of the USA (End of the XIX – Beginning of the XX Centuries). (Abstracts: pp. 4-5) (in Armenian).

27th Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, November 2-3, 2000. Organization and Development of the Armenian Church Community in the USA. (Abstracts: pp. 12-13) (in Armenian).

The Armenian National Culture. Republican Conference. No. XI. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, November 13-14, 2001. The Armenian-American Family. Mode of Life and Customs (End of the XIX Century – Beginning of the XX Century). (Abstracts: pp. 8-10) (in Armenian).

EDITED WORKS:

Abstracts of the 25th Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, May 12-13, 1997 (in Armenian).

Abstracts of the 26th Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, June 29-30, 1999 (in Armenian).

Abstracts of the 27th Conference of Young Researchers. Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia. Yerevan, November 2-3, 2000 (in Armenian).

ABOUT KNARIK AVAKIAN:

Nelli Sahakian. XXIII Conference of Young Researchers. Erevani Hamalsaran. Gitainformatsion Handes (Yerevan University. Scientific-Informative Journal). Yerevan, 1992, No. 3 (74), pp. 15-17 (in Armenian).

Ruben Gasparian, Ruben Sahakian. 24th Conference of Young Researchers of the Institute of History NAS RA. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutiunneri. HH GAA Handes (Herald of Humanitarian Sciences. Journal of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 1994, No. 1 (588), pp. 170-171 (in Armenian).

Nelli Arakelian. The Sources of the Armenian-American Community. Azg. Oratert (Nation. Daily). Yerevan, 1996, March 15, No. 49 (1055), p. 4 (in Armenian) (interview).

New Scientific Degree Conferment. Hayastani Hanrapetutiun. Oratert (Republic of Armenia. Daily). Yerevan, 1996, April 4, No. 64 (1503), p. 2 (in Armenian).

Round Table at the National Academy of Sciences on “Woman and Science”. Hayastani Hanrapetutiun. Oratert (Republic of Armenia. Daily). Yerevan, 1997, July 4, No. 125 (1830), p. 2 (in Armenian).

Rafik Hovhannisian. Pleasant Meetings are Expected for the Reader. Azg. Oratert (Nation. Daily). Yerevan, 1998, September 15, No. 171 (1674), p. 6 (in Armenian).

Hrachia Martirosian. The Premiere As An Alarm. Noratert. Ankakh Oratert (New Newspaper. Independent Daily). Yerevan, 1999, December 10, No. 123, p. 13 (in Armenian).

Gevorg Yazejian. The History of the Armenian Community of the USA. Azg. Oratert (Nation. Daily). Yerevan, 2000, May 4, No. 81 (2049), p. 5 (in Armenian) (book review).

Hrachia Martirosian. Valuable Work. Zhamanak. Oratert (Time. Daily). Yerevan, 2000, B Year, June 21, No. 111 (191), p. 6 (in Armenian) (book review).

Tamar Hovhannisian. Valuable Contribution to the Armenian Community Studies. Hayastani Hanrapetutiun. Oratert (Republic of Armenia. Daily). Yerevan, 2000, June 21, No. 114 (2584), p. 7 (in Armenian) (book review).

Grach’ia Grach’ian. Research on the Armenian Community of the USA. Golos Armenii. Obshchestvenno-Politicheskaia Gazeta (Voice of Armenia. Social-Political Newspaper). Yerevan, 2000, November 28, No. 134 (18639), p. 8 (in Russian) (book review).

Narine Serobian. “The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America.” Yerkir. HYD Hayastani GM Pashtonatert (Yerkir. Daily). Yerevan, 2000, December 15, No. 155 (1409), p. 5 (in Armenian) (book review).

Institute of History. Hashvetvutiun. HH GAA 2000 t. gitakan ev gitakazmakerpakan gordsuneutian himnakan ardiunkner (Account. The Main Results of Scientific and Scientific-Organizational Activities of the NAS RA for the Year 2000). Yerevan, 2001, pp. 77, 115, 118, 224, 259, 262 (in Armenian & Russian).

Haik Khachatrian. Avakian Knarik R. Hayuhiner (Armenian Women). Yerevan, 2001, Part A, p. 41 (in Armenian).

Hrand Ajemian. Knarik Avakian’s book on “The History of the Armenian Community of the USA.” Haradj. Oratert (Forward. Daily). Paris, 2001, 76th Year, April 7-8, No. 20.142, pp. 2-3 (in Armenian) (book review) (to be continued).

Hrand Ajemian. Knarik Avakian’s book on “The History of the Armenian Community of the USA.” Haradj. Oratert (Forward. Daily). Paris, 2001, 76th Year, April 10, No. 20.143, pp. 2-3 (in Armenian) (book review).

Hrand Ajemian. Knarik Avakian’s book on “The History of the Armenian Community of the USA.” Nor Gyank. Hayeren, Angleren, Franseren Ankakh Shapatatert (New Life. Armenian, English, French Independent Weekly). Glendale, 2001, Vol. XXIII, April 26, No. 19, pp. 2, 37 (in Armenian) (book review).

All-Academic Council of the Young Scientists’ of the NAS RA. Young Pricewinners of Gulbenkian Foundation. Gitutiun. HH GAA Tert (Science. Newspaper of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 2001, December, No. 3 (154), p. 1 (in Armenian).

Publications of the “Science” Publishing House of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999-2001. Armenian Mind. Journal of the Armenian Philosophical Academy (Hay Mitk. Hayots Pilisopayakan Akademiayi Handes). Yerevan, 2001, Vol. V, No. 1-2, p. 183 (in English).

Armen Karapetian. Knarik Avakian. The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). “Gitutiun” Publishing House of the NAS RA. Yerevan, 2000, 240 pages. Patma-Banasirakan Handes. HH GAA Handes (Historico-Philological Journal. Journal of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 2001, No. 3 (158), pp. 297-299 (in Armenian) (book review).

Tamar Hovhannisian. Knarik Avakian. The History of the Armenian Community of the United States of America (From the Beginning to 1924). “Gitutiun” Publishing House of the NAS RA. Yerevan, 2000, 240 pages. Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutiunneri. HH GAA Handes (Herald of Humanitarian Sciences. Journal of the NAS RA). Yerevan, 2001, No. 2 (602), pp. (in Armenian) (book review) (in progress).

The History of the Armenian Community of the

United States of America

(From the Beginning to 1924)

Author: Dr. Knarik Avakian

“Gitutiun” Publishing House of the NAS RA, Yerevan, 2000, 240 pages.

Copyright © 2000 K.Avakian. All Rights Reserved.

This work has been done as a Doctoral Dissertation at the

Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia.

Dedication

This work is dedicated

to the 180th and the 80th

memorable anniversaries

of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions(1819)

and

of the Near East Relief(1919),

symbolizing the philanthropy and compassion

of the Christian United States of America,

which have given spiritual, educational-cultural,

social-political and tutorial assistance to the Armenian people.

We express our deep gratitude

to the Executive Director of the Armenian Missionary Association of America,

Secretary of the Armenian Evangelical World Council

Reverend Movses B. Janbazian

for taking under his benevolent patronage

the publication of the history of formation and development

of the Armenian Community of the USA

and for giving a new breath to the self-cognition and self-preservation

of that American ethnic group.

The History of the Armenian Community

of the United States of America

(From the Beginning to 1924)

Contents

Introduction

- The Exodus of Armenians to the United States of America and the Organization of the Armenian-American Community

- Armenians in the Colonial Period of America (Beginning of the 17th Century – First Half of the 18th Century)

- The Emigration of Armenians to the United States of America (1834-1924)

- Distribution and Social-Economic Condition of Armenians in the United States of America

- Distribution of Armenians

- Occupation of Armenians

- Standard of Living of Armenian-Americans

- The Armenian-American Family: Mode of Life and Customs

- Public-Political Relations

- The Armenian-American Unions, Organizations, Parties, Associations, and Clubs

- Ties of the Armenian-Americans with Their Native Cradle

- The Armenian-American Spiritual-Cultural Life

- Church

- Periodicals and Printing-Houses

- Educational and Professional Development

- Literature

- Performing Arts (Theatre, Cinema)

- Music (Singers, Players, Composers, Choirs)

- Fine Arts (Photography, Painting, Sculpture)

Conclusion

Appendix

The Archival Documents of the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey

Concerning the Conditions of the Armenian Emigrants in the United States of America

(End of the 19th Century – Beginning of the 20th Century)

Notes

Bibliography

I.

The Exodus of Armenians to the United States of America and the Organization of the

Armenian-American Community

Under various historical circumstances, the Armenians were compelled to leave their native land and to migrate to different countries of the world, including the USA, for individual, educational, economic, political, cultural, religious and other purposes.

Historically reliable documents reveal that even at the beginning of the 17th century a few Armenians were among the first European settlers in North America (in 1618, the first Armenian, John Martin, set foot in the newly-formed American colony of Virginia and became a tobacco-dealer).

The main stream of Armenian emigrants to USA has started in the first half of the 19th century as a result of the illuminative activity developed by the American protestant missionaries in Ottoman Turkey (the migration of the Armenian youth to American higher and first-rate educational institutions began in 1834).

The emigration of Armenians to the US, which, at the beginning, was of a temporary character and was impelled by educational and economic reasons, was subsequently transformed into a mass exodus following the periodical massacres, slaughter and Genocide organized in Ottoman Turkey against the Armenians (1894-1896, 1909, 1915, 1920-1922); this mass emigration involved tens of thousands of Armenians of both sexes, of various ages and social groups deprived of the prospects of a safe economic, political, cultural and religious life.

The calamitous political situation created in Ottoman Turkey following the First World War and in Czarist Russia, as well as the loss of confidence in the Allied States destroyed in the soul of thousands of emigrants the sacred dream of returning to their Homeland and they definitively established in the New Land of their adoption.

II.

Distribution and

Social-Economic Condition

of Armenians in the

United States of America

As time went by, the Armenian immigrants in the US spread throughout the whole country and settled in nearly all the states, especially in those regions where larger Armenian communities existed (New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Illinois, California, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Connecticut, Wisconsin and other regions). There was, among the Armenians, a tendency to migrate within the US, especially from the eastern states to the western ones.

Taking advantage of the numerous and varied opportunities and freedom, the Armenian settlers in the US were engaged in different professions and occupations and devotedly contributed, with their mental and physical abilities, to the progress of the host country. Owing to their laborious character, moderate and modest mode of life, the Armenian-Americans achieved considerable success, gained a fair amount of property and essentially improved their economic situation and life conditions, gradually adapting themselves to the new life conditions and customs.

III.

Public-Political Life

With a view to reassembling and organizing the Armenian immigrants and exiles in the US, to preserving the Armenian spirit, consciousness, image, character, language and traditions in the American assimilating atmosphere, as well as to making the ties with the native cradle and people more effective and more durable, a great number of diverse unions, organizations, parties, societies and clubs were created in the US.

During the years of the First World War and the following years which were disastrous for the Armenian people, the Armenian community of the US, assembling its entire intercommunal intellectual, financial, public and political resources, has assisted the Motherland and its people by all the possible diplomatic, political, military and human means and has taken part in the enterprises aiming at the defense of the Armenian Action in Europe and in the USA.

IV.

The Armenian-American

Spiritual-Cultural Life

As the Armenians settled and increased in number in the New Land, their spiritual and cultural life developed and became gradually more organized; factors having an important role and significance for the preservation of the nation were created, such as the church, the school and the periodical press, forming definitively the Armenian community of the United States of America.

Compared with the other ethnic groups in the US, the level of literacy of the Armenian settlers was much higher, since they always had attached great importance to education; consequently the community became more and more viable thanks to the growing number of qualified scientists, professors and teachers.

The favorable social and moral atmosphere prevailing in the New World greatly fostered also the formation and development of the Armenian-American distinctive cultural life from the beginning of the 20th century and enhanced the self-manifestation of skillful and talented people in different fields of art (literature, performing arts, music, painting and photography).

The Archival Documents of the

Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey

Concerning the Conditions of the

Armenian Emigrants in the

United States of America

(End of the 19th Century –

Beginning of the 20th Century)

Appendix

The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople has always been the true and sacred bulwark of the Western Armenians as well as of its children exiled by the will of fate. This fact is testified by the documents of exceptional value and interest kept up to the present day at the archives of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople (founded in 1461), with which I had the chance to get acquainted during my private journey to Turkey in 1997.

The documents contained in the fund bearing the general title “America” includes a long period beginning from the 1880s up to the present days. The archival documents are classified in chronological order, consequently, it is possible to have a clear idea about a definite historical period. Thus, if the documents dating from the 1880s contain voluminous materials concerning a given period, then a notable rareness is observed in the materials dating from the years of the First World War, while a complete disappearance of documents is obvious in the following years. In the materials of the post-war period, certain increase in the number of documents is again noted, but not to the former extent. It should be emphasized that the archival materials of the Armenian Patriarchate in Turkey have been periodically “cleaned” as a result of the pressing historico-political circumstances prevailing in the country, while others have been transferred to the United States of America and elsewhere. That is why the materials, which have reached us now, are of a neutral nature, devoid of any political, party, nationalistic and past historical colorations. Nevertheless, these documents, which have passed through the turmoil of historical events and which have been miraculously saved and have reached us, are of an exceptional value as a primary source, owing to their originality and historiographic importance.

These documentary materials include numerous letters, petitions and documents addressed until 1898 to the Armenian primacy of America which was then under the authority of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople (the Armenian primacy of America officially passed under the jurisdiction of the Mother See of Etchmiadzin in 1902) and subsequently to the newly-created Armenian Diocese of America, those addressed to the Armenian Patriarches of Constantinople, to the Armenian Primates of America from the leaders of the various Diaspora organizations and individuals and from the Armenian-populated localities of the USA, as well as those which have been carried to Constantinople under various circumstances.

The above-cited sources provide information about the situation of the Armenian emigrants in the USA, their social-economic conditions, the wish to return to the native localities, the suitability of sending Armenian female orphans from Constantinople with the purpose of preventing the Armenian youth from becoming apathetic toward Armenianness, the necessity of having adequate and efficient clergymen, the adoption of Armenian orphans, the collection and care of orphans, the needs of the Armenian churches in America, the problems concerning the various Armenian denominational churches of the Diaspora, the official ecclesiastical and political relations, the activity of the different Armenian organizations of America, their nation-favouring and fatherland-favouring enterprises, personal and family requests for searching their kins rescued from the Genocide and problems for sending them material aid, as well as a number of discontents, complaints, etc.

The above-mentioned documents kept in the archives of the Armenian Patriarchate of Turkey, being published and put in scientific circulation for the first time, owing to their originality and their historico-cognitive value constitute an important investment for the elucidation and the thorough study of the various aspects of the intracommunal life in a given period of the Armenian community of America, giving credit to the Armenian Patriarchate and the Armenian community of Constantinople, which have passed through the turmoil of various historical and political ordeals and yet have conserved their firm existence up to the present day.

The History of the Armenian Community

of the United States of America

(From the Beginning to 1924)

Summary

A thorough study of the history of the origin and development of the largest and most organized Armenian community in the United States of America is timely and of primary importance as an important link in the whole chain of the studies of the history of the Armenian Diaspora and of the American ethnic groups.

Under various historical circumstances, the Armenians were compelled to leave their native land and to migrate to different countries of the world, including the USA, for individual, educational, economic, political, cultural, religious and other purposes.

Historically reliable documents reveal that even at the beginning of the 17th century a few Armenians were among the first European settlers in North America (in 1618, the first Armenian, John Martin, set foot in the newly-formed American colony of Virginia and became a tobacco-dealer). Any record concerning the exact number of the first Armenian settlers does not exist, but it is known that they were engaged in the different spheres of the economic and spiritual life of the New World.

The settlement of these few individuals in America at that given period was not connected with the subsequent massive emigration to the USA.

The main stream of Armenian emigrants to USA has started in the first half of the 19th century as a result of the illuminative activity developed by the American protestant missionaries in Ottoman Turkey. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the object of which was “to spread the Bible throughout the world,” organized, with the help of the Armenian Mission in 1831 in Constantinople, evangelical sermons, precepts and inspiring talks about the New World, stimulating the national spiritual and conscious awakening and creating a western outlook among the Armenian youth, which groped in an atmosphere of suzerainty of patriarchal customs. The migration of the Armenian youth (especially from Constantinople) to American higher and first-rate educational institutions began in 1834.

In the second half of the 19th century, after the enthronement of Sultan Abdul Hamid II in 1876 and the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878, the exodus of Armenian (Western Armenian) craftsmen and tradesmen from their native cradles acquired a new impetus due to persecutions and economic collapse in Ottoman Turkey. This migration was encouraged also by the revival of the economic, social and political life in the USA following the American Civil War (1861-1865), and already at the beginning of the 1870s, the number of Armenians in the USA had reached 70.

From the 1880s, when the American missionary activities (foundation of churches, schools, colleges and other cultural centers) developed and spread nearly in all the large centers of Ottoman Turkey, the emigration of the Armenians, mainly bachelors (95%), almost from all the provinces and particularly from Harpoot (40%) increased. Among them were peasants burdened under heavy taxes, expropriated workmen, people looking for employment, as well as a number of middle-class tradesmen. Rich Armenian merchants, who had already extended their commercial activities in the European markets, still abstained from migrating to the USA. Near the end of 1880s, the United States, where already 1.500 Armenians lived, had also become a political asylum and a field of free activities for the members of the Armenian revolutionary parties (Hnchakian, Dashnaktsakan).

Most of the Armenian immigrants, who had left their native land for educational, economic and partly for political reasons, regarded the United States as a temporary place for living, studies, employment and fortune. Their majority had no intention to settle there forever and wished to return back to their native cradles after acquiring some material fortune, which would improve the life conditions of their families. Finding favorable social-economic conditions and freedom in the New World, a certain number of Armenians settled gradually there and thereby reduced the number of people returning to the Homeland. Nevertheless, these settlers did not break contacts with their Motherland and they supported their family members materially and morally, promoting further emigration of Armenians.

As a result of continuous violence and massacres against the Armenians in Ottoman Turkey in the 1890s, the former individual departure of Armenians to the US turned into a mass emigration having political, cultural and religious reasons. It included also Armenians from almost all regions of the Empire (Harpoot, Sivas, Erzerum, Trabizon, Bitlis, Cilicia, etc.), who escaped the danger of physical extermination. Thus, if, in 1894, there were about 3.000 Armenians in the US, in 1900 their number had attained 15.000-20.000, even 25.000 according to certain data. These numbers are approximate, since the US Immigration Commission Office began to register the new immigrants according to their national origin starting only from 1899.

Beginning from 1904, the USA became a permanent place of residence also for Armenians (Eastern Armenians) leaving the Russian Empire for economic (the pioneers were the Moosheghians from the village of Gharaghala, region of Kars) and later for political reasons. They received encouraging information about the New World from the Dookhobors and the Molokans exiled to the Caucasus (mainly to the Shirak plain) by Czarist Russia in the 19th century following religious persecutions. The number of emigrants from Russia was not great compared to that from Ottoman Turkey due to milder national oppression and to more satisfactory economic conditions prevailing in Czarist Russia. The extensive emigration of Armenians from Russia to the US, started at the beginning of the century (from Alexandrapol, Igdir, Koghb, Tiflis, Karabagh, Yerevan, etc.), decreased during the First World War, then it slightly increased again in 1917 as a result of the political chaotic situation in the Russian Empire. On the whole, more than 3.500 Armenians left Eastern Armenia for the US during the years 1899-1924.

With the proclamation of “democratic freedom” in 1908 by the Young Turks who came to power in the Ottoman Empire, the emigration of the Armenians to the US was reduced, but it did not stop. A year later, in 1909, the Adana massacres gave a new impetus to the emigration of Armenians horrified by the idea of physical annihilation; it involved not only Cilicia, but also almost all the regions of the Ottoman Empire. On the whole, 51.950 Armenians migrated to the US during the years 1899-1914, predominantly bachelors and those who temporarily left their families in the Homeland.

During the First World War, the emigration to the US continued despite the war-time prohibition policy imposed by the Ottoman government, and 3.620 Armenians left for the US during the years 1915-1919, for the most part those who were miraculously rescued from the Genocide or had lost their families, as well as orphans.

The rise of the Kemalist movement in Turkey, accompanied by the periodical massacres and deportations of Armenians and also the fall of the First Republic of Armenia (1918-1920) gave a new start to the emigration of Armenians, reaching the record number of 10.212 in 1921. These were Armenian survivors collected from the Turkish harems, from non-Christian families, from camps and orphanages by the help of Armenian and American relief organizations.

The new international political relations created after the First World War brought about also a change in the US Immigration policy, and the National Origins Quota was introduced in 1924, limiting to a great extent the immigration of Armenians. At that time more than 120.000 Armenians were living in the US.

Thus, the emigration of Armenians to the US, which, at the beginning, was of a temporary character and was impelled by educational and economic reasons, was subsequently transformed into a mass exodus following the periodical massacres, slaughter and Genocide organized in Ottoman Turkey against the Armenians (1894-1896, 1909, 1915, 1920-1922); this mass emigration involved tens of thousands of Armenians of both sexes, of various ages and social groups deprived of the prospects of a safe economic, political, cultural and religious life.

As time went by, the Armenian immigrants in the US spread throughout the whole country and settled in nearly all the states, especially in those regions where larger Armenian communities existed (New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Illinois, California, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Connecticut, Wisconsin and other regions). There was, among the Armenians, a tendency to migrate within the US, especially from the eastern states to the western ones, which took place according to a certain pattern: at first, beginning from 1834, young bachelors and males who had left their families in their Homeland and hoped to return back there, settled in the educational (mainly New York city) and industrial (mainly Worcester city) areas. Subsequently, in particular from the 1880s, as a result of the increase in the number of immigrants in the US and the decrease in job opportunities in the eastern states and the arrival of wives and children, the Armenians gradually moved to the north-eastern, northern, central, central-western and western (particularly to the agricultural state of California) regions of the US.

Taking advantage of the numerous and varied opportunities and freedom, the Armenian settlers in the US were engaged in different professions and occupations and devotedly contributed, with their mental and physical abilities, to the progress of the host country. Owing to their laborious character, moderate and modest mode of life, the Armenian-Americans achieved considerable success, gained a fair amount of property and essentially improved their economic situation and life conditions, gradually adapting themselves to the new life conditions and customs.

As the Armenians settled and increased in number in the New Land, their spiritual and cultural life developed and became gradually more organized; factors having an important role and significance for the preservation of the nation were created, such as the church (the first, the Armenian Evangelical and the Armenian Apostolic churches were established in Worcester in 1881 and 1891 respectively), the school (the first Armenian-American Vardookian school was established in New York in the late 1880s) and the periodical press (the first Armenian-American newspaper “Aregak” (“Sun”) was published in Jersey City in 1888), forming definitively the Armenian community of the United States of America.

Compared with the other ethnic groups in the US, the level of literacy of the Armenian settlers was much higher, since they always had attached great importance to education; consequently the community became more and more viable thanks to the growing number of qualified scientists, professors and teachers.

The favorable social and moral atmosphere prevailing in the New World greatly fostered also the formation and development of the Armenian-American distinctive cultural life from the beginning of the 20th century and enhanced the self-manifestation of skillful and talented people in different fields of art (literature, performing arts, music, painting and photography).

With a view to reassembling and organizing the Armenian immigrants and exiles in the US, to preserving the Armenian spirit, consciousness, image, character, language and traditions in the American assimilating atmosphere, as well as to making the ties with the native cradle and people more effective and more durable, a great number of diverse unions, organizations, parties, societies and clubs were created in the US.

During the years of the First World War and the following years which were disastrous for the Armenian people, the Armenian community of the US, assembling its entire intercommunal intellectual, financial, public and political resources, has assisted the Motherland and its people by all the possible diplomatic, political, military and human means and has taken part in the enterprises aiming at the defense of the Armenian Action in Europe and in the USA.

The calamitous political situation created in Ottoman Turkey following the First World War and in Czarist Russia, as well as the loss of confidence in the Allied States destroyed in the soul of thousands of emigrants the sacred dream of returning to their Homeland and they definitively established in the New Land of their adoption.

The History of the

Armenian Evangelical Church

- The Evangelical spirit was born among Armenians by adoption and spreading Christianity, and was deepened by the Armenian Illuminators.Evangelism is a reformist movement in the Armenian reality. It represents the great awakening of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries not only in the religious, but also in moral, educational, cultural, social, and economic realms.

- The Armenian Evangelical Church was officially established on July 1, 1846 at Pera, Constantinople (now Istanbul).

- Indisputable and meritorious were the useful duties of the Armenian Evangelical Church for the nation (Western and Eastern Armenia) especially in the following spheres:* language (purification and dissemination of modern Armenian language),* educational (establishment of modern, stage by stage educational system),* publishing (secular and parochial publications, textbooks, periodicals),* music (popular, multiple voiced singing, and organ use in the churches),* family (female education, equalization of female and male rights),* youth (establishment of organizations),* mode of life (the refuse of alcohol, cigarette, gambling, dissolute and wasteful way of life),* charitable (orphan and nation-preserving mission during and after the Armenian Genocide), etc.

- In present the Armenian Evangelical Church in collaboration with the Mother Church is carrying out Christian, missionary, charitable, educational, publishing and other useful activities in behalf of Armenia, Karabagh, Diaspora and Mankind.

HENRY MORGENTHAU

AND

THE ARMENIANS

See also:

K. Avakian. ‘Henry Morgenthaun ev Amerikahayere’ [‘Henry Morgenthau and the Armenian-Americans’] Henry Morgenthaun ev Hay Zhoghovoorde [Henry Morgenthau and the Armenian People]. Yerevan, 1999, pp. 38-49 (in Armenian).

K. Avakian. ‘Henry Morgenthau and the Armenians.’ Armenian Mind. Journal of the Armenian Philosophical Academy [Hay Mitk. Hayots Pilisopayakan Akademiayi Handes]. Yerevan, 2000, Vol. IV, No. 2, pp. 257-276 [to be printed also in Nationalities Papers. New York (23 pages)] (in English).HENRY MORGENTHAU

AND

THE ARMENIANS

It was the fate of Henry Morgenthau (1856-1946) to be the Ambassador of the United States of America in Turkey during the most tragic period of the Armenian history, in the years of World War I. As a diplomat and lawyer, he has devoted all his professional and human abilities to the establishment of justice in Turkey, in favor of the Christians’ elementary rights for life, the defense of their interests and for the mitigation of their sufferings. H.Morgenthau was one of the exceptional politicians who never betrayed the humanistic principles of philanthropy and compassion; continuing the educational and enlightening task of the American Protestant Missionaries started a century before in Ottoman Turkey, he made his valuable contribution by converting it, under the new historico-political circumstances, into a tutorial pro-Armenian Mission.

As early as 1819, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, which had the object of “spreading the Bible throughout the world,” (Jizmejian 1955: 103) had found in the Armenians a reliable stronghold amid the centuries’ old obscure backwardness of the Ottoman Empire for realizing their Christian-reformatory ideas and developing their enlightening activities. As far back as 1831, with the help of the Armenian Mission established in the quarter of Bebek in Constantinople, several Evangelical churches, schools and colleges had been founded, where teaching courses and sermons on European and American educational levels were organized. These institutions, which have been characterized by H.Morgenthau as “means of peaceful penetration” (Amerikyan 1990: 55) of American ideas, have greatly favored also the spiritual and mental awakening of the Armenians and the formation of the pro-western outlook, giving rise to the temporary emigration of the Armenians to the USA, in the beginning for educational purposes and afterwards for economic ones. Many of these Armenian emigrants, finding economic, political, cultural and religious freedom and prosperity in the USA, have settled in the New World, reducing the number of people returning to the Motherland and preparing conditions for the material and moral assistance to thousands of compatriots who emigrated in the following decades owing to pressing historico-political circumstances, as well as for assembling and organizing them as a community.

(Avakian 1996A: 92, 94, 96-97)

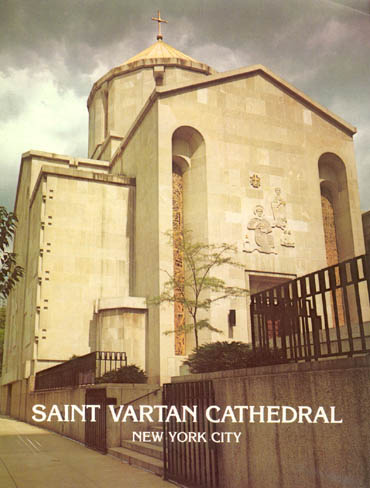

American College at Marsovan.

This building was among the many missionary institutions,

turned over to the use of the Committee. (Barton 1930: 34a)

By 1914, the following institutions were functioning thanks to the humanitarian efforts of the American Board and under the patronage of the USA Embassy almost in every Armenian-inhabited locality of the Ottoman Empire:

* 369 elementary schools with 22.700 pupils and 850 teachers,

* 137 churches with 50.900 adherents, 13.891 communicant members, and 179 native ministers,

* 46 boarding schools and secondary schools with 4.090 pupils,

* 19 hospitals with 39.503 patients,

* 15 missionary centers with 146 ministers,

* 10 colleges with 1.748 students,

* 8 industrial schools,

* 5 nurse-training schools,

* 5 orphanages,

* 4 theological seminaries with 24 students,

* 3 schools for defective (blind, deaf, and dumb) children,

* 2 old people’s homes and others. (Chopourian 1962: 100, 101. Hay 1986: 39. Tootikian 1982: 27-28, 272-273. Papajian 1985: 89)

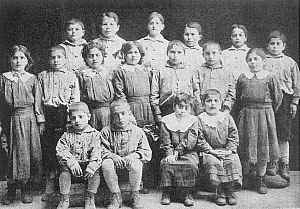

Girls’ Boarding School, Aintab. (Atanalian 1952: 124)

During its already 100 years of existence in Turkey, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, which symbolized American humanism, had invested about 20 million dollars, had endured indescribable moral hardships and had suffered numerous human losses. In the years of First World War, the American missionaries (about 400 in number), faithful to their mission, stayed till the end at their institutions in Turkey, served Christianity and testified the whole world to the sufferings of the Armenians. (Kloian 1985: 40, 44)

“The Missionary Review of the World” (November, 1915) in its article “The American Missionary Interests” has substantiated the centennial interests of Americans towards Armenians as follows: “America has more interests in Turkey than any other country, or possibility than all Europe together. This interest is not political, but humanitarian. In 1819 the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions began work in the Ottoman Empire, and has now for nearly a century prosecuted that work with vigor and statesman _ like foresight and breadth. The missionaries have introduced into the country the printing press and a periodical, literature, modern medicine and sanitation, the modern hospital, new industries and commercial enterprises, and western education, culminating in the well-organized colleges and graduate schools. … The Armenians as a people have been the most responsive to the appeals of modern education. The majority of the 25.000 students in the schools north of Syria have been from this historic and virile race. Thousands have taken graduate courses in the United States. It can be said that America discovered the Armenian race and introduced it to the Western World. It is therefore, eminently fitting that at this time of death-struggle America should be the first to lift its voice in protest, and the most ready to offer its help to save this nation from annihilation.” (Kloian 1985: 102, 103)

The American hospital and pharmacy at Konia,

utilized for care of the orphaned children. (Barton 1930: 35a)

Although the American Ambassador in Turkey, Henry Morgenthau (November, 1913 – Spring, 1916) was called for “… merely to represent his government as worthily as possible, to protect American interests and particularly to watch over the American educational institutions which had accomplished such great things for the Christian populations,” (Kloian 1985: 232) nevertheless he wholly devoted all his diplomatic skills for somehow extenuating the sufferings of Christian populations, especially of the Armenians, and for checking the extermination plans of Young-Turk leaders.

Here is what H.Morgenthau has told Talaat, the Minister of Internal Affairs of Turkey, to stop the persecutions against Armenians and in favor of the American missionaries’ interests: “… Americans are outraged by your persecutions of the Armenians. You must base your principles on humanitarianism, not racial discrimination, or the United States will not regard you as a friend and an equal. And you should understand the great changes that are taking place among Christians all over the world. They are forgetting their differences and all sects are coming together as one. You look down on American missionaries but don’t forget that it is the best element in America that supports their work, especially their educational institutions. Americans are not mere materialists, always chasing money _ they are broadly humanitarian, and interested in the spreading of the justice and civilization throughout the world. After this war is over you will face a new situation. You say that, if victorious, you can defy the world, but you are wrong. You will have to meet public opinion everywhere, especially in the United States. Our people will never forget these massacres. They will always resent the wholesale destruction of Christians in Turkey. They will look upon it as nothing but willful murder and will seriously condemn all the men who are responsible for it. You will not be able to protect yourself under your political status and say that you acted as Minister of Interior and not as Talaat. You are defying all ideas of justice as we understand the term in our country.” (Kloian 1985: 266)

Being born at Mannheim (Baden), Germany, of Jewish origin, H.Morgenthau’s humanitarian views were exceeding to narrow, nationalistic or local limitations. Opposing to Turkish racialist mentality, he admonished to the Turk leaders, that “… above all considerations of race and religion, there are such things as humanity and civilization … .” (Kloian 1985: 232, 266) Then he added about his origin and his political views: “… I am not here as a Jew but as American Ambassador. My country contains something more than 97.000.000 Christians and something less than 3.000.000 Jews. So, at least in my ambassadorial capacity, I am 97 per cent Christian. But after all that is not the point. I do not appeal to you in the name of any race or any religion, but merely as a human being. You have told me many times that you want to make Turkey a part of the modern progressive world. The way you are treating the Armenians will not help you to realize that ambition; it puts you in the class of backward, reactionary people.” (Kloian 1985: 266) Backwardness, about which H.Morgenthau has expressed himself in his historical memoirs as follows: “I have no intention of describing the terrible vassalage and oppression that went on for a five centuries; my purpose is merely to emphasize this innate attitude of the Muslem Turk to people not of his own race and religion _ that they are not human beings with rights, but merely chattels, which may be permitted to live when they promote the interest of their masters, but which may be pitilessly destroyed when they have ceased to be useful. This attitude is intensified by a total disregard for human life and an intense delight in physical human suffering which are the not unusual qualities of primitive peoples.” (Kloian 1985: 242)

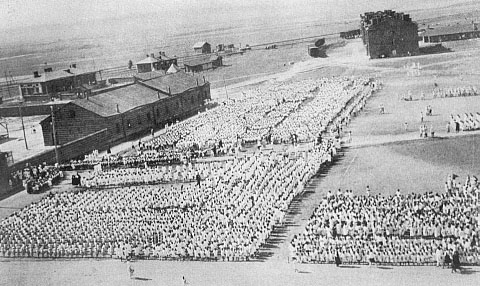

This group of human wreckage represents tens of thousands

when first approached with aid. (Barton 1930: 22a)

During the years of war in Ottoman Turkey and under strengthened censorship conditions, H.Morgenthau received detailed information about the deportations, massacres and slaughters occurring in the eastern provinces through the American missionaries, who, overcoming road difficulties and risking their lives, came to the Embassy to witness to what they had seen and heard. H.Morgenthau has written in his memoirs: “For hours they (missionaries – K.A.) would sit in my office and, with tears streaming down their faces, they would tell me of the horrors through which they had passed. Many of these, both men and women, were almost broken in health from the scenes which they had witnessed. In many cases they brought me letters from American consuls, confirming the most dreadful of their narrations and adding many unprintable details. The general purport of all these first-hand reports was that the utter depravity and fiendishness of the Turkish nature, already sufficiently celebrated through the centuries, had now surpassed themselves. There was only one hope of saving nearly 2.000.000 people from massacre, starvation, and even worse, I was told _ that was the moral power of the United States. These spokesmen of a condemned nation declared that, unless the American Ambassador could persuade the Turk to stay his destroying arm, the whole Armenian nation would disappear.” (Kloian 1985: 263) The European powers were also of this opinion.

Starving, diseased and filthy, these were the children

of the Near East who were gathered into the orphanages

in the early days of the disaster. (Barton 1930: 85a)

The American Embassy in the Ottoman Empire used all its diplomatic potential to stop the mad plans of the Young Turk leaders, “… for which civilization will hold the Turks responsible.” (Kloian 1985: 260) H.Morgenthau demanded from the Young Turk leaders a guarantee of safety and security for the Americans, Englishmen, Frenchmen and for the Armenians. But Turkey did not give a guarantee for the security of Armenians and had no intention to give up its plans of extermination of a whole nation. On the contrary, the Young Turk leaders announced that the case of their attitude towards Armenians was of no concern to the USA and that the Armenians would mostly gain, if they were freed from the tutorial assistance of the USA, something which would urge them to rely only upon the good nature of the Turkish government. (Amerikyan 1990: 119, 275, 281, 291)

Nevertheless, H.Morgenthau did not miss the opportunity to use his authority in favor of the Armenians. Thus, on the occasion of the greatest religious holiday, Bayram, he interceded with Enver and obtained the liberation of seven Armenians condemned to death by the Ismir military tribunal. The Ambassador H.Morgenthau, realistically evaluating the situation created in the Ottoman Empire for the Armenians and persuaded that it was necessary to take measure “to rescue permanently the remnants of these fine, old, civilized, Christian people from the fangs of the Turks,” he applied to the American Government for moving to the USA 550.000 Armenians miraculously saved from the Genocide and succeeded in charging the Young Turk leaders 1.000.000 dollars as part of the transportation expenses. With the help of its councils and missionaries, the American Embassy organized the distribution of foodstuff, clothing, medicines and other important aids supplied by the humanitarian institutions of USA to the rescued Armenians of Anatolia. (Morgenthau n.d.: 16. Kloian 1985: 50, 52)

Orphanage children. (Barton 1930: 54a)

In the hardest years of First World War, the American Ambassador in Turkey, H.Morgenthau, not satisfied with the efficiency of his activities, resigned from that post, and has written about it in his memoirs: “My failure to stop the destruction of the Armenians had made Turkey for me a place of horror, and I found intolerable my further daily association with men, who, however gracious and accommodating and good-natured they might have been to the American Ambassador, were still reeking with the blood of nearly a million human beings. Could I have done anything more, either for Americans, enemy aliens, or the persecuted peoples of the empire, I would willingly have stayed. The position of Americans and Europeans, however, had now become secure and, so far as the subject peoples were concerned, I had reached the end of my resources.” (Kloian 1985: 244)

In the USA H.Morgenthau resumed his humanitarian mission with a new impetus. He had an active participation in the re-election of the greatest politician, President Woodrow Wilson, considering it an important enterprise both for the USA and for the whole world. Together with President W.Wilson, H.Morgenthau has taken part in post-war peace negotiations, in military missions and in other important international enterprises. (Kloian 1985: 244. Hovannisian 1974: 338)

From the very beginning of the First World War, the Armenians, who had increased in number in the USA due to various historical circumstances, assembled the entire intercommunal public, intellectual, material, party and other resources to succor the native land and its people in distress for defensive and reconstructive purposes in collaboration with the American diplomatic, political, military, benevolent and other organizations.

The Armenian-Americans have participated both in volunteer movements in the native land in helping the enormous number of needy compatriots and emigrants and in the various political, diplomatic and military enterprises in Europe and the USA suing the Armenian Action. Among such kind of Armenian-American nation-supporting institutions were initially the pro-educational organizations, then, during the First World War and in the period following it, the widow-helping, orphan-helping, poor-helping and rehabilitation organizations, the compatriotic unions, the political parties (the Hnchakian party in 1890, the Dashnaktsakan party in 1895, the Ramgavar-Azatakan party in 1921), the American headquarter of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (in 1908, Boston), the Armenian Red Cross of America (in 1910, New York), the Armenian Missionary Association of America (in 1918, Worcester) and other similar organizations. (Avakian 1996B: 177-183)

Among the active political Armenian-American institutions were the Interparty Council (in November, 1914, Boston), subsequently renamed the National Defense Armenian-American Council (NDAC) and the Society for the Defense of National Interests (SDNI) (in 1915, New York) these two being later amalgamated into the Society for National Defense, the Armenian National Union of America (ANUA) (in March, 1917, Boston), the plenipotentiary representative of the National Paris Delegation in the USA, which had established the Armenian National Union Publicity Office (in 1918, New York), subsequently renamed Press Office and still later, Publicity Committee. (Teghekagir 1922: 8-12, 30, 31)

The Chairman of the USA Central Committee of the Armenian General Benevolent Union, Mihran Karageuzian, has realized a pro-Armenian cooperation with the General Secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Rev. Dr. James Barton. The latter, in reply to Ambassador H.Morgenthau’s telegram from Constantinople in September, 1915, informing that “the destruction of the Armenian race in Turkey is rapidly progressing,” therefore it is important to save the rest, founded the American Committee for the Examination of Armenian Persecutions with the help of the Armenian Home of Cleveland. This committee, consisting of American missionaries, humanists, industrialists and professors gave birth to the American Committee for Armenian Relief. Its chairman, Rev. Dr. James Barton has said on the occasion of its creation: “The Armenians have no one to speak for them and it is without question a time when the voice of Christianity should be raised.” The American Committee for Armenian Relief collected 100.000 dollars and sent it to the USA Ambassador in Turkey H.Morgenthau for the needs of Armenians. (Hooshamatyan 1965: 934. Barton 1930: 4-6)

Soon, when it became obvious that the Armenian tragedy had acquired enormous dimensions and when H.Morgenthau announced in November that “the shocking reports of the eye-witnesses pointed out that a genocidal course was in progress,” the American Committee for Armenian Relief spread its activities and became incorporated with the corresponding groups from Syria and Palestine, and was renamed the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief. This organization has continued its benevolent mission even in 1917, when the diplomatic relations between the USA and Turkey were deteriorated. (Hooshamatyan 1965: 935. Barton 1930: 4-5. Hovannisian 1974: 133) The American press of that time had written on this occasion: “The settling of the “Armenian Question” is a task for statesmen, but the feeding and rehabilitation of Armenia, which is being carried on by the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, is a task for every man and woman in America.” (Kloian 1985: 205)

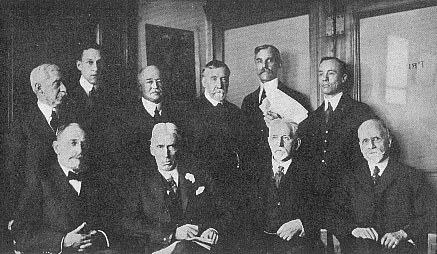

Executive Committee known first as the Armenian Relief Committee,

then as the Armenian and Syrian Relief Committee,

later as the American Committee for Relief in the Near East and

incorporated by act of Congress as the Near East Relief

(taken upon the return to this country of Ambassador H. Morgenthau

from Constantinople in January, 1916).

Left front: Henry Morgenthau, Cleveland H. Dodge, James L. Barton, Samuel T. Dutton.

Left standing: Alexander J. Hemphill, Harold A. Hatch, Stanley White,

William W. Peet, Edwin M. Bulkley, Charles V. Vickrey.

Three of these men, Messrs. Dutton, Hemphill, Dodge,

died in the service of the Committee.(Barton 1930: 8a)

H.Morgenthau, who after his resignation, had the intention to make the people of the USA know about the sufferings of the Armenians, and to engage them as much as possible in supporting the Armenians in need, has expressed himself as follows: “If I dared repeat the tales I have heard, shown to and signed, they would make men and women weep and every one would see the need of sympathy and help. I wish I had the power to picture an Armenian refugee encampment and to tell how an American missionary hospital fed from its back door a thousand starving persons a day on an average of 3 cents a person with the $30 a day we gave it… . What this great country should do to show its appreciation of the wonderful blessings that have been showered upon us is for each one of us to make up his mind to do his share. Picture that you are personally responsible for the starvation of one or two persons if you do not give funds to save them. Twenty-five dollars will enable an Armenian family to be established in comparative comfort. I believe every person would be happier to sacrifice something and give $25 for the Armenians. … We have been hearing of the brotherhood of men. If we are all brothers, and we are, have we a right to live on in comfort and luxury and allow these people to starve? I do not think we have. I believe that it is our duty, it is our privilege, for each of us to assume the guardianship of as many of the Armenian people as we can. … I believe the moral force of America will be doubled and trebled, if the rest of the world understands that we are ready and willing and anxious to help the suffering masses.” (Kloian 1985: 149)

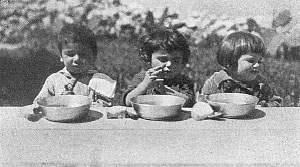

Three plump cherubs giving thanks for the food

supplied them with American money. (Barton 1930: 262a)

Starting from April 24, 1919, the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief was named the American Committee for the Relief of Near East and by the decision of the Congress, it was renamed in August Near East Relief (Chairman – Rev. Dr. James Barton; Vice-Chairman, member of the Board of Trustees – H.Morgenthau). The mentioned Relief Committee was a national structure, since it got approval from the whole American people, the Congress and the President of the country, it collaborated with the national benevolent organizations, the American Red Cross and the other charitable institutions. The Near East Relief supplied 116 million dollars, including 25 million dollars’ worth of food and clothing of the US government, as well as 1 million dollars collected by the Armenian-Americans. The Near East Relief with its hospitals, orphanages, schools and workshops established in 11 countries of three continents, has cured, sheltered, fed and inspired new hope to tens of thousands needy people, without distinction of religion, has educated 132.000 orphans becoming “… the symbol of humanity and compassion … on the bloodstained land of the Middle East.” (Hooshamatyan 1965: 935, 944. Kloian 1985: 341. Hovannisian 1982: 398. Barton 1930: 6, VIII, X, XI)

Work was supplied to destitute refugee women in Syria

to afford them a meager living and because

the blockade had depleted the markets of cloth. (Barton 1930: 66a)

As a responsible person in the Near East Relief, in 1920, H.Morgenhtau called to save, at any price, the survivors of the Armenian Genocide: 1.200.000 naked and hungry adults, 250.000 orphans, 250.000 women enslaved in Turkish harems, 100.000 of which had already been saved by the efforts of the Committee. “If they were good enough to fight and die for us when we needed their help so sorely, are they not good enough to be given some crumbs from our plenty? … Let the American slogan now become – Serve Armenians for a little while longer with life’s necessities that they may be preserved for the day of national freedom and rebirth, which no people more truly and greatly deserves. As an eye-witness H.Morgenthau has given his arguments: “The deportations and massacres during the war were not spontaneous uprising of unorganized mobs, but were the working out of a well-plotted plan of wholesale extermination in which regular Turkish officers and troops took part as if in a campaign against an enemy in the field.” Hence, he has concluded: “If America is going to condone these offenses, if she is going to permit to continue conditions that threaten and permit their repetition, she is party to the crime. These peoples must be freed from the agony and danger of such horrors. They must not only be saved for the present but either through governmental action or protection under the League of Nations they must be given assurance that they will be free in peace and that no harm can come to them.” (Kloian 1985: 341)

On the 7th of December, 1924, the Near East Relief, in collaboration with the Armenian General Benevolent Union, had organized the International Golden Rule Sunday enterprise. In their joint declaration there was written: “INTERNATIONAL GOLDEN RULE SUNDAY will be observed in twenty or more countries by those who have not forgotten that the Golden Rule is the only principle by which people may dwell in amity together. The observance of the day will test our sincerity. It will prove a spiritual exercise for the prosperous. It will provide a vital food supply for the homeless and the starving. It will be an expression of international fellowship and good will.

The Golden Rule is a universal creed, the common denominator of all religions. International Golden Rule Sunday, December 7, is intended to be a day of plain living and high thinking; a day for personal stock-taking, for comparison of our deeds with our creeds, for measurement of our lives by a universally accepted standard to ascertain how nearly we have attained an ideal. …

Why observe International Golden Rule Sunday?

For the sake of our own souls and our own children. Luxurious living may be as injurious to the prosperous as is starvation to the less fortunate.

For the sake of the children of the Near East. They perish if we fail.

For the sake of international brotherhood and world peace. There will be no permanent world peace until the Near East question is settled. What greater influence for peace could be set free in the world than a generation of children given life through international generosity and taught love by international example. …

Tens of thousands of innocent children in the Near East are without father, mother or country. They have no responsible relative to provide support. They are practically all under sixteen years of age. … There are 95.000 children in refugee camps who should have the benefit of at least a brief period of orphanage training. They have no legal claim upon the over-populated, over-burdened, refugee-ridden territories to which they have been exiled.

These children are wholly dependent upon outside philanthropy. …