SULTAN ABDUL HAMID II AND HIS PAN-ISLAMIC POLICIES

Armenian Kurdish Relations in the Era of Kurdish National Movements (1830-1930)

[PRELUDE and INTRODUCTION]

[I. FROM TIMES IMMEMORIAL TO THE EIGHTEEN HUNDREDS]

[II. A REBELLIOUS CENTURY]

[III. THE ERA OF HE RELIGIOUS SHEIKS]

[IV. SULTAN ABDUL HAMID II AND HIS PAN-ISLAMIC POLICIES]

[V. THE CONSTITUTIONAL PERIOD, WORLD WAR I AND …]

[VI. SHEIK SAID ALI’S REBELLION AND THE FORMATION OF “HOYBOUN” …]

[VII. THE ARARAT REBELLION AND THE KURDISH QUESTION IN]

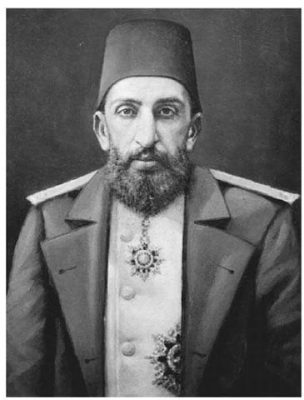

IV SULTAN ABDUL HAMID II AND HIS PAN-ISLAMIC POLICIES

“We Armenians must try to share our enthusiasm with them. For this, we do not have any other means except out motivation, with which we could strengthen ourselves and become live models, and show that we Armenians are capable of defending our and our neighbor’s rights as well. If we create this vigor, then we will have the Kurdish ally. Otherwise, Armenians will remain as raiding and robbing targets for the Kurds, and at no time will they accept us as partners in the struggle against the common enemy.”

Kristapor Mikayelian

(Founding member, A.R.F)

After the major Kurdish rebellions of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire changed its policies towards the Kurds. The sultan tried to establish a common denominator between the government and the Kurdish ruling class. This way, the Ottoman government expected to gain the Kurds on its side. By offering them a partnership in the ruling process, the government was to gain unconditional Kurdish cooperation in exchange.

The protagonist of this new policy was sultan Abdul Hamid II himself. He needed the Kurds as allies to disseminate and advocate his Pan-Islamic ideology within the Kurdish communities. Abdul Hamid aimed at restoring the sultanate and the empire and to bring back the glory of the old days, after decades of weakness and corruption. When Kurdish leaders sensed that the sultan was ready to meet their demands, they willingly offered their services to him.

Before proceeding any further, a brief analysis of the Pan-Islamic ideology that Sultan Abdul Hamid II advocated will suffice.

When this capricious sultan occupied the Ottoman throne, the country was already on the verge of decline. Consecutive wars had weakened the government and had emptied its coffers. Several vassal territories in the European part of the empire had by then regained their freedom. On the other hand, Europe grew so strong that it controlled the foreign and even the domestic politics of the Ottoman Empire. European powers brought the Ottoman economy under their supervision. Its representatives demanded the sultan to carry out reforms for the minorities (Armenians, Greeks, etc.). Europe insisted that this was necessary to secure the empire’s internal tranquility and save it from further disintegration.

Against this enormous European pressure, Abdul Hamid devised his own political agenda. Through the teachings of Jamal Ul Din Al Afghani (a Muslim ideologue) and his direct tutelage, he emphasized the importance of Islam as a cohesive force which was destined to amalgamate the empire’s mostly Muslim peoples. Abdul Hamid intended to recreate a strong central government. This could only be achieved by the unification of the ethnically diverse yet religiously homogeneous Muslim population of the empire. The sultan’s contention was that if he could accumulate this religious power in his hands, he would be able to restore his political authority as well.

With such power, Abdul Hamid could block European interference in his internal affairs. At the same time, he could control the minorities’ demands of autonomy. He could even suppress new separatist movements. As a result of the Pan-Islamic policies of Abdul Hamid, the enmity between the Armenians and the Kurds escalated to new hights after 1880. The two neighboring people were unable to tolerate each other. According to Sasuni: “The Kurdish national movement stopped completely at about the same moment the Armenian national freedom struggle was born. At this juncture, a new Turko-Kurdish united front was shaped. In the decades that followed, it became the primary evil against the Armenian struggle for freedom.”[1]

The absorption of the Kurdish “nobility” within the ruling Ottoman elite was to be one of Abdul Hamid’s canniest moves ever. Kendal notes that:

“… This policy of centralization, based on the integration of the Kurdish leaders, enabled the empire to make good use of the Kurdish people’s warlike qualities, partly as backing for an eventually conflict with the Russians, but mainly as a means of repressing the national movements of the various peoples struggling against Ottoman rule such as Armenians, Arabs, Albanians, and even the Kurds.”[2]

In every corner of the eastern vilayets, Kurds viewed Armenians as infidels who could be robbed, and mimed. In Alashkert, Vaspurkan (vilayet of Van), Pasen, and Diarbekir, armed bands of Kurdish tribal warriors named Hamidiye— after sultan Abdul Hamid II, who sanctioned their establishment– raided and looted Armenian towns and villages. They even murdered Armenian peasants. Some of these atrocities were the consequence of fanatic religious speeches that filled Kurds with blind hatred and transformed them into vigilantes. Anarchy was now dominant from on end of Western Armenia to the other. To defend themselves against this Kurdish menace, Armenians tried to get organized. Some Armenians were outlawed because of injuring or killing a raiding Kurd. They were obligated to flee form Ottoman justice and take refuge in the mountains as fugitives. Soon these fugitives grew in number in the remote mountainous areas. They organized themselves into fedayeen groups with the intent to avenge their families.[3] Arapo and Mekho in Sasun, Huno in Alashkert, Akripasian and Koloshian in Vaspurakan were thus transformed into legendary “outlaws” who became leaders of these groups. Those modern Robin Hoods fought Kurdish and Turkish army units. They tried to defend their rights and seek justice with their own hands. “However, these bands were few in number and their actions had but a limited effect on the situation in general. They were unable to restrain the Kurdish terror which by now had grown to an unbearable magnitude.”[4]

Kurdish atrocities against Armenians reached their peak in 1895, when thousands of Kurds, with the help of regular Turkish regiments, attacked the secluded mountainous Armenian villages of Sasun and ruthlessly massacred the population. Notorious amongst Kurdish Chieftains in their dealings with Armenians were Musa Beg and his brother Chacho. Musa Beg’s evils were spread all over Sasun and even Mush. The government was unable to deny the many protests which Armenian villagers submitted against him. The authorities unwillingly exiled Musa Beg into Western Turkey. Yet the Kurdish chieftain returned after a while and was even appointed a leader of a Hamidiyeh regiment.[5]

Another event that is worth mentioning is the battle of the Birm. Kurds tried to subjugate the Armenian villages of the Birm district. Yet Armenian villagers defended themselves. Having exhausted their ammunition and supplies, their resistance was destroyed and they were massacred. Similar battles occurred in Ghizilaghaj, Hirgert and other parts of Ottoman Armenia.[6]

A. The Rebellions of Sasun (1892-1904)

After 1890, the Turkish government and the Kurdish tribes focused their attention on the mountainous Armenian villages and settlements of Sasun. Abdul Hamid was very specific in choosing this Armenian “freedom nest.” Subjugating the last of the Armenian strongholds would evidently silence the Armenian liberation movement and its demands of autonomy. Furthermore, this would serve as an example to other minorities who entertained ideas about autonomy or even separation from the Ottoman Empire.

In 1892, skirmishes between Kurds and Armenian villagers became frequent all over Sasun. Kurdish chieftains were outraged, because Armenian villagers refused to pay extra taxes. On the other hand, Armenians argued that the Ottoman government heavily taxed them. Moreover, being poor villagers, they were unable to pay the extra taxes demanded by the Kurdish tribal leaders. However, it must be stated that it was at about this time that some Armenian agitators, mainly from the Henchakian party, had moved to Sasun to entice the villages of this remote Armenian dwelling. Acknowledged as patriots by local Armenian villagers and as revolutionaries, terrorists, and even traitors by the government, it was these nationalist instigators who encouraged the villagers to refuse to pay the Kurdish lords.

The first serious Kurdish advance towards Sasun started in the summer of 1894. Murad, the Henchakian leader in Sasun organized the bombing of the Satan’s Bridge, (Sadani Gamurch), which was still being built. It was to serve as a strategic passage to the mountains of Sasun and was to provide ample employment for Kurdish laborers. Outraged by this act, Kurdish forces moved toward the Armenian stronghold on the first of August. Kurdish Hamidiye cavalrymen and troops from fourth Turkish army battalion from Bitlis soon joined them. The villages of Sasun were besieged, yet neither the Kurdish nor the Turkish forces were able to advance because of the tight-armed resistance of Armenian villagers and the few nationalist agitators helping them.

The outraged Mushir Zeki Pasha, the commander in chief of the joint Turko-Kurdish forces, planned and executed yet another offensive in 1895. In a way, these attacks were reminiscent of Ottoman assaults launched against Kurdish Amirs during earlier decades of the nineteenth century.

This second offensive lacked any success. However, Armenian resistance was also weekend because of several weeks of intense fighting, Turkish troops and Kurdish irregulars were finally able to pierce through Armenian front lines and enter Sasun. The “eagles’ nest” was subjugated. More than a thousand villagers were killed; some one hundred and sixty fedayeens were captured and murdered by torture.[7]

The atrocities of the Turkish troops and the Kurdish tribesmen in Sasun attracted European interest. European ambassadors intervened on behalf of Armenians to stop the brutality and the meaningless massacres. On May 11, 1895, the ambassadors of England, France, Russia, and other European states handed Sultan Abdul Hamid a memorandum demanding swift reforms in the six Armenian vilayets of Eastern Anatolia. Sultan Hamid had no other choice but to agree to the reform project, at least to silence Europe whose representatives had already traveled to Sasun and had witnessed the cruelties first hand.

What sultan Abdul Hamid accepted was the memorandum known as “The May Project of Reforms.” However, he not only Prevented it from being enforced, but also even continued his aggression on Sasun during 1896-1897. Armenian villagers did stage limited acts of self-defense. In the long run, however, they were always to be defeated against the broader Turkish and Kurdish forces. Thousands of Armenians perished of brutality in the period 1895-1897. Susan revolted once again in 1904. But it was once again silenced by similar measures.

During Sasun’s fight for self-defense in 1895, Armenian nationalistic agitation was already surfacing in other parts of Ottoman Armenia. Acts were staged even in the capital city of Constantinople. Events like the seizure of the Ottoman Bank by A.R.F. fedayeens and the disturbances that occurred at about the same time in some suburbs of the capital alarmed the sultan. Abdul Hamid was not dealing with the problem in the secluded mountains of Sasun, but in the very heart of his capital, exposed to European powers and the international community at large. By accepting the May reform project, Hamid was able to silence Europe and free his hand in seeking revenge against Armenians. He dumped hundreds of thew into prison. He brilliantly staged a series of massacres near and even inside Istanbul under the very eyes of the European ambassadors. Hamid presented his policies as measures and tactics taken against revolutionaries and traitors. To toll of these Hamidian Massacres was some three hundred thousand Armenian dead.[8] In the Eastern vilayets, Kurds once again became the tools of the slaughter.

The May reform project showed that European powers intervened simply at the last moment and on a solely humanitarian basis in order to preserve Armenian existence. Armenians never gave up hope from Europe. Yet it seems that the Armenian provinces were too remote to attract such importance as that of the magnitude that Greece or the Balkans possessed.

The only Christian power interested in Western Armenia was Russia. It had labored and gradually absorbed the Eastern Armenian provinces, namely the Khanates of Erivan, Nakhichevan, Gharabagh, and Gianja from Kajar Iran as well as the territories of Kars and Artahan from the Ottoman Empire. Armenian nationalistic agitation and political societies first fermented in the Eastern provinces of Armenia, as well as Tbilisi, the capitol of Georgia.

In European capitols such as London, Paris, Vienna, Geneva Armenian University students had already organized themselves into political groups. They discussed the Armenian question in the Ottoman Empire, and they tried to find the means with which an autonomous Armenian entity could be materialized. In fact, Ottoman Armenia was the birthplace of the first Armenian political party, the Armenakan Party, created in Van, in 1885, through efforts of an Armenian intellectual, Mekerdich Portukalian, himself a student from Europe, who, after returning to his hometown, started his nationalistic career as a teacher. Portukalian surrounded himself with the active youth of the city, and motivated them towards the cause of freedom.

In 1887, the second Armenian political Party, the Henchakian Party, was formed in Geneva by a group of Armenian students. It soon started to publish its organ, Henchak (literally The Bell, after Gologol—also Bell—the organ of the Russian anarchists and their founder, Bakunin), advocating Armenian freedom.

The first attempt at uniting Armenian nationalists and revolutionary intellectuals failed in Tiflis where the Federation of Armenian Revolutionarieswas created in August 1890. Two years later, the Federation was transformed into a new party, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (A.R.F.). It assumed the role of the protector of oppressed Armenians within the Ottoman Empire, and it devoted itself to the cause of their liberation. For this reason, the A.R.F. realized the importance of Kurdish cooperation and tried to approach this tribal people and to bring it closer to the Armenian cause. This was not a simple task to achieve. Armenians had almost nothing to offer the Kurds except their true friendship and an honest faith in the power of a unified Armenian-Kurdish struggle and what it could accomplish.

It was not easy to make the Kurdish tribes understand this important and vital message, especially since they were repeatedly hearing the opposite from their Ottoman rulers. Armenian nationalists realized this difficulty early on. They were convinced that in order to bring the Kurds to their camp, a show of force was required, because it was only might and vigor that could influence a Kurd. Armenians also approached some Kurdish intellectuals in Istanbul. They even established a limited communication with some of the so-called “liberal” Kurdish chieftains and they tried to make them aware of the reality.

B. Relations During Hamid’s Reign.

Abdul Hamid encouraged and motivated the Kurdish tribes towards suppressing the Armenians. In many instances Armenians were cast as outlaws. Kurdish brutality against them was even permitted by law. The sultan armed the Kurdish tribes and then formed the Hamidiye corps from among the fiercest of the Kurdish fighters. Incorporated within the framework of the Ottoman army, these Hamidiye regiments proved to be a real menace for Armenians. In a matter of months they accomplished what regular Ottoman troops took years to accomplish. Elucidating this period Sasuni states: –

“During this long period of enmity between Kurds and Armenians (1880-1908), the Armenian cause suffered. This enmity took a heavy toll on Armenians. Its memories remained even when later conditions were changed between the two people. In order to shed some light on the future developments of Armenian-Kurdish relations, we have to add here that many attempts were made to ease the situation and to decrease the hostility between the two neighbors.”[9]

What were these “attempts” and what kind of work was done in order to bring a compromise?

After the first A.R.F. general convention, almost all of its leaders who were sent to Western Armenia tried to approach the Kurdish tribes. It was necessary, even imperative, to make Kurds understand that the Armenian freedom movement was directed towards the Ottoman and not the Kurds.

Even before the retaliatory Khanasor Expedition, during which the A.R.F. fedayeen punished the Kurdish Mazrik tribe (stationed on the southeastern border region between Iran and the Ottoman Empire), to show Kurds that they do not have a free hand in raiding and killing Armenian peasants, the A.R.F. Central committee of Iran established direct negotiations with the Kurdish tribes of Vaspurakan,with the purpose of achieving an accord with them. The negotiation had only a partial success. Some Kurdish tribes began to cooperate with the Armenian parties and the fedayeen groups, especially in such tasks as messenger services and arms transportation. First transporting military supplies from Russia to the Iranian border districts and from there to Van, Mush, and Sasun in Western Armenia accomplished this. This network operated smoothly through the help of Kurdish tribes dwelling along the transportation route.

It must be noted, however, that Kurdish tribes and villages that cooperated with the Armenian Movement were limited in number. Most of them, it seems, participated in the effort out of fear, because they were situated within the field of action of the Armenian fedayeen groups. Only a very small number of individual Kurds collaborated with Armenians because of their belief in the justness of the Armenian cause. Some even joined the Armenian fedayeen groups and died heroically fighting side by side with their Armenian comrades.

Before attempting to reach a final evaluation of the various means employed at creating a more positive Armenian-Kurdish relationship, a cursory mention of some notable Armenian patriots who endeavored to establish a mutual understanding between these who neighboring people will suffice. The list of those patriots dates back to the 1850’s when clergymen like Khrimian Hayrig (Megerditch Khrimian). Hayrig means Father in Armenian), then the Catholicos of Monastery of Akhtamar in Van, Karekin Servantziants, a priest and author at the same monastery, tried to advocate Armenian-Kurdish cooperation through their literature. In the 1890’s this work was continued by figures such as Rev. Vartan (Vartan Vartapet) of Saint Garabed’s Monastery in Sasun, Hrayr Tzhokhks (Armenak) of Sasun, and Keri (literally uncle, Rupen Shishmanian) of Dersim.

Rev. Vartan was a respected clergyman. He was also a devoted nationalist. During his administration, the monastery became a hiding place for Armenian fedayeen and a depot for arms and ammunition. Rev. Vartan realized very early in his career that an understanding must be reached with the Kurdish tribes of Hazzo (Sasun). He dedicated his life to accomplish this important task. He created some inroads with Kurds through his pious character. The “Keshish” (literally priest, father) as the Kurds used to call him thus brought some ease to the Armenian villages that he served.

Creating a positive atmosphere between Kurds and Armenians was a priority to Hrayr of Sasun, another devoted figure of the Armenian Nationalist Movement. He started his revolutionary career as a member of the Henchakian Party and was initiated by Mihran Damadian, the first Henchakist agent to Sasun. Later, Hrayr joined the ranks of the A.R.F. After 1895, he became the central figure of the Armenian Nationalist Movement in Sasun. He stringently advocated Armenian-Kurdish cooperation. His teaching became the basis for other revolutionary figure such as Kevork Chavush and Rupen Ter Minassian. Hrayr journeyed to the Armenian and Kurdish villages of Sasun disguised as a dervish (beggar, pious man). Once his presence was established he motivated the illiterate masses towards the cause of freedom. However, these calls remained incidental and their results negligible. Kurdish Sheiks and Begs sometimes cooperated with the A.R.F. on a personal basis and for only short periods of time.

As for Keri, he became the central figure of the Armenian freedom struggle in the districts of Dersim and Erzinjan as early as 1895 and continued to be so until 1899. The A.R.F. Bureau (highest executive body) sent Garabet Ghumrikian as its agent to organize these remote Kurdish territories and motivate its leaders towards freedom. Keri, who was by now heading a fedayeen group, participated enthusiastically in this task. However, he was discouraged by the politics of the A.R.F. Bureau, which directed most of the organization’s potential towards Sasun and Vaspurakan, thus leaving Keri alone with no funds or dedicated personnel to continue his task in Dersim. Meanwhile, Keri succeeded in establishing firm and friendly ties with the Kurdish leaders of Dersim. He enjoyed a high popularity within the Kurdish tribes there. Most of them respected him and always listened to his advice. Keri’s efforts blossomed very late, when Sheik Said Ali of Piran rebelled against the Turkish government in 1924-1925. By then Keri was already martyred. Eventually, he did not witness the results of his dedicated endeavor.

Stories of devoted Kurdish fedayeen and their adherence to the Armenian cause of freedom occupies a special chapter in the history of the Armenian Revolutionary Movement. This in itself could be the subject of an important historical research, which is outside the scope of this narrative.

The Kurds never suspected, however, that the Armenian massacres were only the first phase of a more general plan, whose second act would be their–i.e. The Kurd’s–own distinction. By the time Kurds realized this, it was already too late. In 1897, atrocities similar to those in Sasun occurred in the city of Van. Armenians were obliged to take defensive measures. When Armenian resistance was weakened, the militants of the three Armenian political parties operating in Van—after negotiating with the authorities through the offices of the Russian consul – decided to retreat from the city to save the population from eminent massacres. However, as soon as they started to retreat, they came under heavy fire and were attacked by a Kurdish mob. The Armenian fedayeen took refuge in the hills surrounding Van. They were besieged and murdered by Kurdish irregulars, who hunted them down.

Recalling this incident Rupen Ter Minasian writes: –

“With this (the Van resistance), the leaders of the three Armenian parties of Van and most of their devoted followers were massacred. And so they died on the path of freedom, which they adored. This was a tremendous blow not only for the parties involved but to the Armenian people of Vaspurakan as well. The most devoted and educated of the Armenian nationalists were martyred. After this blow, they [Henchakian Party, G.M.] never recovered. Its organization in Van was halted. With the martyrdom of Avetisian, the Armenakan Party in turn received a decisive blow. Its remaining members soon joined the A.R.F.”[10]

The cruelty of the Turkish regiments and especially that of the Kurdish mob proved once again that there was no, nor can there be any, mutual trust between Kurds and Armenians. It was as if cooperation with Armenians was a misnomer for Kurdish mentality. The A.R.F. finally realized that the mild means with which it advocated cooperation were useless. As a direct result, the Khanasor Expedition was organized in late 1897. This retaliatory act heralded the massage that the A.R.F. did not forgive those who spilled Armenian blood in the hills surrounding Van. Moreover, the message was clear: severe punishment was to be extracted against Kurds thereafter.[11] On the other hand, the expedition was truly an example of discipline and organization. The fedayeen that attacked the Mazrik tribe acted as true soldiers. They directed their rifles only against Kurdish tribal warriors, thus completing their task with a minimum number of civilian casualties.

Nevertheless, most Kurdish aggression towards Armenians had no certain motive behind it. Kurdish warriors had to comply with the battle calls of their sheiks and tribal chieftains who followed Sultan Abdul Hamid’s policies almost blind-foldedly. Sasuni mentions that at the eleventh hour before the Khanasor Expedition commenced, Vazken Teroyan, known also as “Vazken of Vaspurakan”– not being in favor of such an overt military act and preferring the continuation of covert, underground organizational efforts instead– decided against participation in the campaign and ordered his fedayees (guerilla fighters) back to Van. On their way back, the group was scouted and was caught in a fight against a sizable Kurdish force which was about to surround it when Avo, the Kurdish scout of Vasken’s group told the fedayeen to direct all their rifles in the direction of the leader of the marauders whom he pointed by his finger. Eventually the Kurdish chieftain was fatally wounded. Amazingly enough, the Kurds halted there offensive and retreated at the exact moment when they could have given the fedayeen the decisive blow.[12]

Many such incidents are recorded in the history of the Armenian National Movement. Ultimately, they prove the point that Sasuni tries to make. Obviously, Kurds followed their leaders blindly, yet they deserted them at the first sign of danger.

C. Relations With Kurdish Intellectuals.

If brutality and mayhem were the marks of Kurdish raids in the Eastern vilayets, Their intellectuals in Europe and even in the capital, Istanbul showed totally different attitude towards Armenians. A Kurdish inelligentsia had started to mushroom in the different European capitals after 1898. Kurdish students traveled to Europe to achieve higher education. Living in Western societies and having engulfed the social understandings and the nationalistic philosophies of the day, those young and active Kurdish intellectuals realized the erroneous directions towards which the illiterate Kurdish masses were driven. They tried hard to inform the Kurdish masses and motivate them to live in cohesion and mutual understanding with their Armenian neighbors. Some Kurdish students even wrote pamphlets in this regard. An example of such an essay is the one written by Abdulrahman, the son of Bedirkhan Bey, whose Armenian translation appeared in the A.R.F. organ, Droshak. The original Kurdish pamphlet was secretly distributed within the Kurdish tribes. It was titled “Kurtlere Khitap” (A Call To The Kurds), and it advocated cooperation with the Armenians and their cause. With simple words and sentences Abdulrahman told his brethren about “the evil Sultan Abdul Hamid and his treacherous policies,” insisting that joining hands with the Armenians is important “because their struggle against the Ottoman oppressor is just, and Kurds must take an example from it.”[13]

The A.R.F. organ dedicated two editorials to the question of mutual cooperation between Kurds and Armenians. In them, the A.R.F. formally expressed its position of welcoming Kurds to join the Armenian struggle. At the same time, however, it advised them not to show hostility towards Armenians or their cause…

By 1900, the Armenian National Movement had acquired a respectable reputation. Kurds realized that they either had to cooperate with Armenians or continue their enmity and raid and be confronted by the vengeance of Armenian fedayeens. The A.R.F. still advocated ideas of collaboration and mutual understanding. The party’s literature of the day reflects this, since it uses the examples of the nineteenth century Kurdish Amirs and their endeavors in establishing good relations with their Christian neighbors. Of course, this was done to bring Kurds closer to the Armenian cause of liberation, since there was a clear understanding in this regard between all Armenian nationalists: only with the accomplishment of a strong Armenian-Kurdish cooperation could the Armenian cause be effectively solved.

In 1903 Malkhas (Artashes Hovsepian), an American-Armenian physician and an A.R.F. member, undertook a tedious and extremely dangerous journey to the southernmost part of Kurdistan and reached its capital, Shamsdinan. The objective of the trip was to meet with Sheik Sedekh, the son of the famous Sheik Obeydullah, and establish negotiations with him. Malkhas persuaded the sheik to join his forces with the Armenians.[14] This trend did not continue, because the A.R.F. was unable to send another envoy to the sheik in 1904. Eventually, Sheik Sedekh’s enthusiasm faded away. He brought his participation only late in 1908, after the declaration of the Ottoman constitution.

The A.R.F. also tried to show friendly attitudes towards the raya (serf) Kurdish population, whose life was as miserable as that of the Armenian peasants. Between 1907-1908, the A.R.F. launched a campaign against Turkish and Kurdish tax-farmers and absentee landlords. It went as far as assassinating some of the most cruel and bloodthirsty of those bankers, who were a real threat to Armenian and Kurdish peasants alike. In fact, Sultan Abdul Hamid had swarmed the Eastern vilayets with his agents and spies “the eyes and the ears of the Sultan” and he knew about the assassination plans. However, he was unable to stop the killing of some of his best servants. This elevated the esteem of the A.R.F. and the Armenian movement among the raya Kurds. Some of them even joined the Armenian movement.

The achievements mentioned above were only partial successes. Many Armenian patriots gave their lives as a price for their trust in the Kurdish character. Those were “true advocates of a positive Armenian-Kurdish relationship and had dedicated most of their work for the achievement of that goal.”[15]

[1] Sasuni, “Kurteru Eva Hayeru Azatagrakan Sharzhman Pulere,” Hayrenik, 1930, # 7, p. 124.

[2] Chaliand, People Without, p. 33.

[3] For information regarding the organization and the ideology of its leaders see:

Sasuni, “Kurteru Eva Hayeru”, Hayrenik, 1930, # 7, p.124.

[4] Ibid, p. 124.

[5] Ibid, pp. 125-127. Also see: Sasuni, Kurt Azgayin Sharzhumnere, pp. 162-166.

[6] Sasuni, “Kurteru Eva Hayeru”, p. 127.

[7] For more information about the 1894-96 insurrection in Sasun see: Ruben, Ter Minassian, Hay Heghabokhagani me Hishataknere, Hamazkaine Press, Beirut, 1974, Vol. III, pp. 70-113. Also see: Sasuni, Kurt Azgayin Sharzhumnere, pp. 166-169, and

Sasuni, “Kurteru Eva Hayeru”, pp. 127-128.

[8] The number of Armenians massacred is a matter of debate. While some sources

estimate it at about three hundred thousand, others, like Sydney Fisher figure it at around one hundred thousand. This numbers represent Armenians who were massacred in Sasun, the eastern vilayets and also in pogroms in and around the capital city, Istanbul during 1894-96. Nevertheless, what all sources agree upon is that these “Hamidian Massacres” (After sultan Abdul Hamid, who instigated them) were the first planned [G.M.] extermination that the Ottoman government undertook. Moreover, the magnitude of these massacres show, that they exceeded all previous forms of atrocities committed against Armenians in the empire.

[9] Sasuni, “Kurteru Ev Hayeru,” pp. 1280129.

[10] Ter Minassian, Hay Heghapokhakani, Vol. II, p. 106. About the battles of Vaspurakan, see: Ibid, pp. 93-106. About the life and work of Rev. Vartan, Hrayr, Keri, and other Armenian patriots who were the real advocates of Armenian-Kurdish cooperation and friendship see: Ter Minassian, Hay Heghapokhakani, Vol. III, pp. 130-140, 240-270. As for the 1904 second rebellion of Sasun, first Ter Minassian’s voluminous work contains an abundance of first hand information about it, since he was present and an eye witness of the events he describes.

[11] The Khanasor Expedition is a huge subject in itself. It can easily be the topic of another research narrative because it possesses a momentous literature of its own. In the context of this narrative, it was cited as an example of the armed propaganda that the A.R.F. deployed to show that Armenians were not going to remain passive, but would even retaliate– with force if necessary—to protect their lives and fortunes.

[12] Sasuni, “Kurteru Eva Hayeru,” p. 129.

[13] Ibid, pp. 130-133. Regarding this matter also see: Abdul Rahman Bey, “Koch Kurterun”[Kurtlere Khitab], Droshak, 1898, # 6, p. 51. Droshak published the Armenian version of said document. On the other hand, the A.R.F. was instrumental in procuring thousands of copies of the pamphlet in Turkish to distribute it in Kurdistan.

[14] Sasuni, Kurt Azgayin Sharzhumnere, pp. 185-188.

[15] Ibid, pp. 189-191. An example of this sort of Turkish treachery is Ghasem Beg, who joined the ranks of the A.R.F. and even became a member of one of its regional committees. He assumed the name “Nor Melik” (New Prince, G.M.) However, He committed a dreadful crime that caused the death of several devoted and seasoned Armenian freedom fighters, fedayeens. According to Ter Minassian, Ghasem Beg invited the fedayeens who were visiting his village to his home where he fed them and then, with his accomplices, killed them while they were fast asleep.