The Armenian Legion

Cilicia Under French Mandate , 1918-1921

Related Topics

[INTRODUCTION and THE FRENCH ADMINISTRATION]

[THE ARMENIAN LEGION]

[ECONOMY AND HEALTH CARE]

[SOCIAL AND POLITICAL LIFE]

[THE THORNY ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE and CONCLUSION]

The Armenian Legion

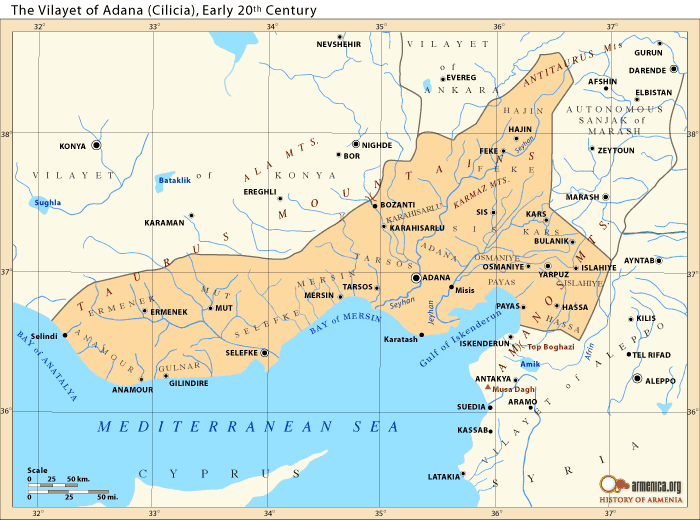

From December 1918 to November 1919 the four battalions of the Armenian Legion constituted the majority of French occupation forces in Cilicia. The five thousand Armenian soldiers of the legion were deployed in the plain of Cilicia with advanced posts at Bozanti and Baghche. During this period, the British units maintained their positions in the Taurus and Amanus tunnel system as well as the Eastern Occupational Zone. Although several Algerian companies strengthened the four Armenian battalions, at no time did french troops in Cilicia reach the number that was necessary and sufficient to control the region.

Allied commanders had on several occasions commended Armenian soldiers for their bravery and perseverance. French commanders had repeatedly assured Armenian legionnaires that they were not being sent to Cilicia as forces of occupation but as liberators to form the nucleus of an Armenian army that was to be created soon. These initial French assurances were soon forgotten. A systematic policy of dishonoring and discharging Armenian soldiers was implemented.

The idea of forming an Armenian fighting unit alongside the French army in the Levant was that of Boghos Nubar Pasha, a prominent Egyptian Armenian who had served in several ministerial posts under the Khedives. In 1916, Nubar Pasha left Egypt for Paris to head the Armenian National Delegation.[1] After several months of negotiations with the representatives of the French and British governments Nubar Pasha was able to convince them to adopt his idea and to sign an agreement authorizing the formation of an Armenian volunteer unit which was “to be deployed only in the Levant for the sole purpose of liberating Cilicia from Turkish rule.”[2] The agreement also stated that the proposed Armenian battalions were to be trained by the French and considered as part of the French Army.[3] They were to fight alongside the Allied troops and later be deployed in Cilicia where an autonomous Armenian entity was to be created as a result of an eventual Allied victory.[4]

Following the agreement, a French military delegation was dispatched to Egypt. On November 26, 1916, the formation of the first battalion of the Legion d’Orient (a neutral name that was chosen for the Armenian unit so as not to antagonize the Turks and endanger the lives of Armenian deportees in Syria) was officially initiated. The training of Armenian volunteers began at Port Said.[5] This city was chosen because of its proximity to the Armenian refugee camp where thousands of exiles from Musa Dagh (a mountainous Armenian enclave near Antioch) were relocated after being rescued by the French navy in September 1915.

The first battalion was recruited from this refugee camp. Soon, Syrian Arabs and other Christian soldiers, who had either deserted the Ottoman army or were captured by Allied troops in Yemen and/or southern Mesopotamia, joined the Legion d’Orient. The French military command relocated the Legion to Cyprus, where new Armenian volunteers from Egypt, Europe, and the United States joined its ranks. By January 1917, the Legion d’Orient had almost five thousand men in training. The soldiers were divided into four battalions ready to engage in battle.

That opportunity came in September 1918, when orders were issued to Allied forces in the Levant, under the command of General Edmund Allenby, to attack the Turkish Yildirim army, stationed in Palestine.

French sources state that at least three of the Armenian battalions were instrumental in the battle of Arara, which ended in total Allied victory. Twenty-three Armenian soldiers died and scores were wounded as a result of the September 18 offensive.[6] After a short rest, the Armenian battalions marched north with the rest of the Allied troops that liberated Syria and the Lebanon. The march from Palestine to Beirut was full of hardships, since the area was suffering an acute famine. The lack of means of transportation was also a major hardship for the advancing Allied troops. Many were forced to stay behind when a wave of Spanish influenza hit the Allied army.[7] Nevertheless, the Armenian battalions finally reached Haifa. After a short respite, they continued their march to Beirut.

Because of some misunderstanding and friction between the Armenian volunteers and the predominantly Muslim population of Beirut the French relocated the Legion d’Orient to the coastal town of Junieh, where it remained until its deployment in Cilicia.[8]

At this juncture, the Legion d’Orient was renamed the Legion Arménienne. British and French naval vessels carried its battalions to Cilicia. The First, Second and Third battalions went ashore at Mersin and were stationed in Mersin, Tarsus, Adana, Jihun, and Bozanti. The Fourth battalion came ashore in Alexandretta. Its units were deployed in Deort Yol, Osmaniye, and Baghche, where skirmishes occurred with Turkish armed bands.[9]

The French military command in Cilicia had stationed several Algerian units of the Ninth Tirailleurs in and around the port city of Alexandretta. Those units were soon strengthened by two companies of the Fourth Armenian battalion, much to the dismay of the Turkish population. In his memoirs, Dikran Boyadjian, who at the time was an Armenian volunteer serving in Cilicia, states that the Turkish population of the city had established friendly relations with the Muslim Algerian soldiers and incited hatred and intolerance among them against the Armenian volunteers.[10]

On February 10, 1919, a small fist fight between Armenian volunteers and Algerian soldiers turned into a shooting match that continued for three days and resulted in the death of fourteen Armenians and several Algerians. Although the Algerians were as much to blame for the incident, the French put the whole fault on the “undisciplined” Armenian soldiers and arbitrarily disarmed and discharged the four hundred soldiers of the tenth and thirteenth companies of the Fourth Armenian battalion.[11] The disarming and discharging of the Armenian volunteers came at a crucial moment when every single French soldier was desperately needed to bring Cilicia under the control of the newly established French administration. Numerous Turkish and Kurdish armed bands were terrorizing the population between Ayas and Osmaniye and hindering Armenian refugees from returning to their towns and villages.[12]

Although much of the change in French attitude toward the Armenians should be attributed to French politicians in Paris, there were several local factors that perpetuated this change. Interesting in this regard is what some Turkish sources reveal about the scandalous actions of some Turkish notables who tried and apparently succeeded in winning over some greedy French officers whose only aim was to pile riches before returning to France. Costly presents and bribes are but few of the dubious methods that Turkish notables used to win over those officers.[13] N. Paillares, a French journalist who at the time was residing in Constantinople, stresses the fact that bribe taking, a centuries old Ottoman habit, was a major problem for the French and had infested their virtues. He also underlines what he calls “a policy of harems” which Turks employed to win over some French officers. Paillares writes: “The [Turkish] Pashas and Beys opened wide the doors of their villas and presented their beautiful unveiled women to the greedy young [French] officers.”[14]

Armenian volunteers were told that they had been deployed in Cilicia as liberators of a region that was to be theirs. In their memoirs, some volunteers find it irrational to be branded as culprits who were punished and discharged for allegations advanced by Ottoman officials questioning their behavior. Armenian soldiers were stunned when the French administration prevented them from rescuing Armenian women and children who were taken in by Turks during the 1915 deportations and were forcibly Turkified.[15] Armenian volunteers, most of whom were uneducated, could not have grasped the subtle complexities of French foreign diplomacy, which was propelled by political and economic interests and considerations rather than noble principles. “Our every move” concludes one volunteer, “even as harmless as it may have been, was considered an undisciplined act and we were severely punished for it. The French had only one-way with which to silence us, to disarm and discharge us from our duties. They did just that. They dismantled all the Armenian units stationed from Bozanti to Yenije and brought in their Algerian units instead.”[16]

The French tried to defend their actions by stating that disciplinary measures against Armenian volunteers were necessary in order not to alienate those Turks that were opposed to Kemal and could be won over. By silencing Armenian soldiers and by discharging them en masse, the French military command not only weakened the already feeble French occupation forces, but also gave the Kemalist bands the opportunity to intensify their attacks on Armenian villages and French garrisons and to win the support of the Turkish population whom the French were ostensibly campaigning to win over.[17]

Armenian soldiers had numerous other reasons to distrust the French administration. Foremost among these was the fact that by mid-1919 the French had not only discharged more than half the volunteers, but also neglected their previous promise of recruiting new ones for the Armenian Legion and raising the number of its soldiers to twelve thousand men.[18]

Moreover, during their military service, the Armenian soldiers were deprived of many of the rights that regular French and even Algerian soldiers enjoyed. They were classified as “assisting soldiers.” Their pay was much less than regular French soldiers, even though their serving contract stated that they were to be paid on an equal basis with regular French soldiers. In his memoirs, Boyadjian argues that the French allocated less money and materials to the Armenian Legion than necessary for regular operation. As a result of this neglect, Armenian volunteers faced severe shortages in food, clothing, communication devices, and means of transportation.[19]

Perhaps more aggravating was the fact that the Armenian battalions were deprived of an Armenian officer corps. The French officers who were assigned to these battalions turned a deaf ear to the problems that Armenian soldiers encountered. The Legion had only four Armenian officers with the rank of non-commissioned lieutenants who had earned their ranks even before joining the Armenian force.[20]

The Legion also had a score of soldiers with the rank of sergeant. “It is unfortunate,” writes John Shishmanian, an American Armenian and one of the four officers,” that there are several educated soldiers among the Armenian volunteers who should have been considered for the rank of lieutenant after almost two years of service in the French army.”[21]

The disarming and discharging of Armenian soldiers also resulted in the resignation of other Armenian legionnaires. Many of the discharged volunteers left Cilicia. Those who preferred to remain were soon recruited into the Armenian guard units that were formed under the guidance of the Armenian National Union, a central body entrusted with the task of regulating and defending Armenian communal life in Adana and the plain of Cilicia.[22]

Mihran Damadian, who served in Cilicia as the representative of the Delegation of Integral Armenia from June 1919 to August 1920, worked hard to stop Armenian volunteers from resigning. He entreated them not to be demoralized by the change in French attitude. In a circular addressed to Armenian volunteers and printed in the local Armenian newspapers on July 24, 1919, Damadian asked the Armenian legionnaires not to leave their posts, since their mission was not yet accomplished. Damadian also advised the Armenian volunteers to obey their French commanders, “because soldiers are to obey and not to criticize orders.”[23]

Damadian’s work was complemented by that of the Union of Armenian Legionnaires. Armenian officers who held the executive posts in this Union worked desperately to keep the First, Second, and Third Armenian battalions intact immediately after the French summarily discharged the Armenian volunteers of the Fourth battalion. Numerous circulars advised and even urged Armenian volunteers not to resign.[24] Despite these efforts, by mid-1919 the Armenian Legion was reduced to about five hundred men. This small force was then put under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Fly-Sainte-Marie who replaced Lieutenant Colonel Romieu. No effort on the part of the French administration was made thereafter to revive the Armenian battalions.

Thus, after only six months of deployment in Cilicia, the French rendered the Armenian Legion impotent. “The nucleus of the future Armenian Army,” a French reference to the Armenian Legion, was totally forgotten and was never reiterated.

As a microcosm of Armenian existence in Cilicia during 1919-1921, the Armenian Legion experienced the bitterness of shifting French policies. For France, the Legion Arménienne had already served its purpose. Given the future calculations of French politics in the Levant, Paris saw no need for an Armenian force.

[1] Yeghiaian, Adanayi Hayots Patmutiun, p. 442.

[2] Dikran Boyadjian, Haygakan Lekeone, Badmagan Hushakrutiun (The Armenian Legion: A Historical Memoir) (Watertown: Baykar Printing, 1965), p. 133.

[3] Guevork Gotikian, “La Legion d’Orient, Le mandate français et l’expulsion des Arméniens,” Revue d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, tom III, numéro special, 1999, pp. 251-324. This lengthy article also introduces the main agreements concerning the formation of the Legion d’Orient. Especially important is the first document in the appendix (pp. 314-318, and p. 256 of the article) titled “Instruction sur l’organisation de la Légion d’Orient,” which contains a point stressing that in accordance to a special instruction soldiers serving in the Legion will have “leurs allocations, qui seront en principe equivalents a celles du soldat français.” Also, instruction No. 7.966-9/11 of November 26, 1916 mandated that besides being treated in an equivalent fashion to French soldiers, soldiers of the legion would also have their monthly salaries, pensions, and family allocations in accordance to what French soldiers were entitled to. Of course these initial agreement points were never implemented,

[4] Ibid., p. 165.

[5] Yeghiaian, Adanayi Hayots Patmutiun, pp. 422-423.

[6] Boyadjian, Haykakan Lekeone, p. 133.

[7] Ibid., p. 165.

[8] Yeghiaian, Adanayi Hayots Patmutiun, p. 432; Kasbar Menag, Giankis Ughinerov (On The Paths of My Life) (Beirut: Shirag Press, 1968), pp. 33-34; Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus, pp. 141-144. Zeidner tries to present the Armenian legionnaires as rude and rogue soldiers who were only amused by harassing people. He states that they were not welcomed in Beirut because of fights that they instigated with local Muslims.

[9] Boyadjian, Haygagan Lekeone, p. 191.

[10] Ibid., p. 192.

[11] Ibid., pp. 195-196; Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus, pp. 148, 155-158. Once again, Zeidner states that it was the Armenian soldiers who instigated fights with the local Muslims (notice the careful use of the word rather than Turks). However, he admits that one such incident started when Armenian legionnaires were trying to rescue an Armenian girl from a Turkish harem.

[12] Boyadjian, Haykakan Lekeone, pp. 197-198.

[13] Dalkir, Yigitlik Gunleri, pp. 45, 48.

[14] Torossyan, Kilikiayi Hayeri Azgayin-Azatagrakan Sharzhumnere, p. 110.

[15] Boyadjian Haykakan Lekeone, pp. 202-203.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 30, p. 65.

[18] Boyadjian, Haykakan Lekeone, p. 204.

[19] Ibid., p. 216.

[20] Ibid.; those were:- Lieutenant John Shishmanian (United States); Lieutenant Vahakn Portukalian (France); Lieutenant Aspiran Vahe Sahatjian; Lieutenant Papazian ( from the French Legion Etranger).

[21] Boyadjian, Haykakan Lekeone, pp. 216-217.

[22] Yeghiaian, Adanayi Hayots Patmutiun, p. 565.

[23] Ibid., p. 563.

[24] Ibid., pp. 578-579.