Cilicia Under French Mandate , 1918-1921

Armenian Aspirations, Turkish Intrigues, and French Double Standards

Related Topics

[INTRODUCTION and THE FRENCH ADMINISTRATION]

[THE ARMENIAN LEGION]

[ECONOMY AND HEALTH CARE]

[SOCIAL AND POLITICAL LIFE]

[THE THORNY ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE and CONCLUSION]

INTRODUCTION and THE FRENCH ADMINISTRATION

INTRODUCTION

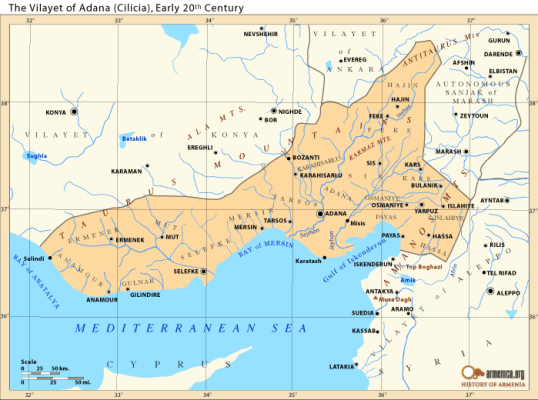

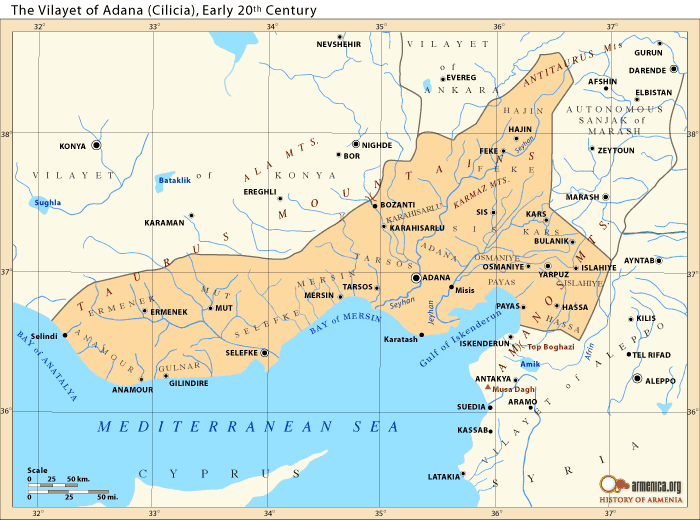

As a result of the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Cilicia, an Ottoman region in the southeastern corner of Asia Minor, was brought under French control from December 1918 until October 1921. The initial months of occupation were marked by measures taken first by the British and then by the French to bring over 170,000 Armenian refugees back to their homes. The majority of repatriates were Cilician Armenians, whom the Turks had forcibly deported to the Syrian Desert in 1915.

During the war, the Allied powers had repeatedly assured Armenians and other minorities of the empire that they were soon to be freed from the Turkish yoke. The French, at least during the initial stage of their occupation of Cilicia, tried to repopulate the region with Armenians. Encouraged by French support, Armenians hoped to create an autonomous Armenian entity in Cilicia.[1]

The rise of Turkish nationalism under Mustafa Kemal, ethnic rivalries between Armenians and Turks, and a shift in French policy to one of rapprochement and then of agreement with the Turkish nationalist movement shattered Armenian dreams and compelled thousands of Armenians to forsake the area with the retreating French forces.

On October 30, 1918, aboard the British battleship Agamemnon anchored in the Turkish port of Mudros, the representatives of a defeated Ottoman Empire signed a humiliating document of surrender. The Turkish defeat in the battle of Arara (Palestine, September 1918) against the Allied expeditionary force under the command of General Edmund Allenby was a major factor in forcing the Ottoman Empire out of World War I. According to the stipulations of the armistice, the defeated Ottomans had to accept the Allied occupation of those Ottoman territories that were considered “strategic” for preserving peace. Moreover, article 16 of the Mudros Armistice stated, among other things, that the defeated Turkish army — stationed at the time in Adana, Cilicia — was to retreat north of the Bozanti-Hajin-Marash line, where its soldiers were to be demobilized. Accordingly, the British were to occupy the province of Adana and to place military units in the highly strategic Amanus and Taurus tunnel system that was still under construction.[2] The British were the first to send their forces to Cilicia after the armistice. The British thought they could hold on to Cilicia even though that was contrary to the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement by which Britain and France had practically divided the Levant between themselves.[3] The agreement stated that, in the event of an Allied victory, France was to acquire Syria together with Cilicia and other territories in eastern Anatolia and Mesopotamia.[4]

Towards the end of December 1918, a French civil administration with small French military contingents was installed in Cilicia. However, because of the lack of sufficient forces, the British remained for one more year. The British and thereafter the French encouraged Armenians who had been deported from Cilicia to repatriate. As a result, over 170,000 Armenian refugees returned. However, postwar rivalries between the French and British allies on the one hand, and Kemalist incursions, on the other, gradually destroyed Armenian aspirations towards an autonomous Cilicia. On October 21, 1921, France signed the Ankara Agreement with the Kemalists and relinquished Cilicia to them.[5] By January 1922 the region was brought under Kemalist control.

This paper focuses on the province of Adana from the repatriation of Armenians in late 1918 to their subsequent evacuation. Issues such as the characteristics of the French civil and military administrations, Franco-Turkish, Franco-Armenian, and Armeno-Turkish relations, the Cilician economy during French occupation, the deployment of the Armenian Legion in Cilicia, and Armenian national and communal life in Cilicia will be assessed. Although the scope of this paper is the plain of Cilicia, an area encompassing the cities of Mersin, Tarsus, Adana, Jihun, Osmaniye, Deort-Yol, Toprak-Kale, Ayas, Payas, and Alexandretta, the main focus will be on the provincial capital of Adana.

THE FRENCH ADMINISTRATION

In accordance with the stipulations of the Mudros Armistice, British forces occupied Cilicia in November 1918. It remained under direct British control until February 1919, when a French civil administration was installed there (although British forces remained in Cilicia until the end of 1919). During the four months of British control, the existing Ottoman administration was kept intact awaiting new orders from Jerusalem, the Allied headquarters in the Levant, as to how it should be replaced. Because of this uncertainty, many of the cadres of the Turkish army defied the order to retreat, and were placed in the still-intact Ottoman administration.[6] It was these new Turkish officials that, disguised under their new administrative titles, constituted the nuclei of the Kemalist committees, which became a menace to the French administration during the following three-year period.[7] Moreover, Turkish and French sources agree that retreating Turkish troops sold or simply left a good portion of their weapons (totaling some twenty five thousand rifles and depots of ammunition) behind for the Turkish population. These were hidden in underground caches.[8]

The armistice also tolerated the formation of a gendarme unit, all of whose three thousand members were recruited from among the retreating Turkish troops.[9] This police force was put under the command of Colonel Hashim Bye, an ex-Ottoman officer who “was continuing to wage war against the allies.”[10]

Because of the numeric weakness of French combatants in the Levant, the Allied headquarters in Jerusalem agreed to keep the nineteenth Indian Brigade of the British army, under the command of General Norman Leslie, in Cilicia.[11] In December 1918, the Legion Arménienne, which was stationed in the city of Beirut after the victory at Arara, was sent to Cilicia under the command of lieutenant colonel Louis Romieu. The fourth battalion of the Armenian legion was stationed in Alexandretta (Iskandarun), and its units were deployed in that port city, Deort-Yol, Osmaniye, and Baghche. The first, second, and third battalions went ashore at the port of Mersin and were deployed in Mersin, Tarsus, Adana, Jihun, and the outpost of Bozanti.[12] Thus, a relatively small force of five thousand Armenian soldiers had to secure an area of fifty thousand square kilometers. [13]

Although the French brought in some Algerian battalions after the British left, the insufficient number of French soldiers in the province continued to be a real problem for the French administration. Moreover, problems created by the shortage of combatants were worsened by the lack of munitions, fuel, food, and means of transportation. [14]

Problems the French faced in Cilicia

The Allied headquarters divided the Levant into four occupational territories. Cilicia comprised the Northern Occupation Territory with the city of Adana as its administrative center.[15] Colonel Edouard Bremond, whom the French government named administrator-in-chief of Cilicia, arrived in Adana on February 1, 1919, and assumed his duties as the head of the civil administration of the province. [16] The cities of Marash, Aintab, Urfa, and Kilis were not incorporated within the jurisdiction of the French administration. Instead, they were assigned to a newly established fifth occupational zone and put under the command of the British Desert Mounted Corps whose administrative center was in Aleppo.[17]

At the time when the French civil and military administrations had started to organize and regulate living conditions in Cilicia, Georges Picot, the French High Commissioner in Syria and Armenia[18] and one of the signatories of the Sykes-Picot agreement –whose position and duties, according to Bremond, were “poorly defined and subsequently caused much friction between him and the local officials in Cilicia and elsewhere”[19] — encouraged and even urged Armenian deportees stationed in Syria to repatriate to Cilicia.[20] A total of 120,000 deportees, mostly women, children, and elderly people thus returned home. They were transported to Adana by railway, where they were temporarily assigned to specially built camps awaiting orders from the French administration that would allow them to reclaim their towns and villages.[21] During this same period, some fifty thousand Armenian deportees repatriated to their cities and villages in the Eastern Occupation Zone under the command of the British Desert Mounted Corps.[22]

Colonel Bremond’s administration was put to its first test in the beginning days of April 1919. On the sixth day of the month, a special administrative order was released from the office of the Chief of Administration stating that “all lands and properties, movable or otherwise, which belonged to Armenians prior to their deportation in 1915 and were later confiscated by local Turkish authorities and distributed among the Turks in Cilicia, had to be returned to their original owners in a period of two months.” Moreover, the administrative order stated that even if people had actually bought such properties from the Turkish authorities, they should immediately return them to their original owners if they were claimed as such. The newly revived Agricultural Bank was to compensate those who had bought such properties.[23]

The Turks, to whom the administrative order was apparently directed, regarded the French demand as an infringement on their rights. The French administration did not initiate this order, but rather acted on instructions received from Allied headquarters in Jerusalem. As soon as it had divided the Levant into several occupation zones, the Allied headquarters had formed a special committee that sat in Haifa, Palestine, to decide on what action to take to enable deportees to repossess their lands and properties after repatriation. The committee had studied the issue and had presented its recommendations to Allied headquarters, which, in turn, had instructed French and British administrations in the occupational zones to act in accordance with the presented recommendations.[24]

Turkish sources have more than bitter words for the special court system that the French administration had formed to look after and decide in land ownership cases. Rejep Dalkir, a former officer in the Turkish army who, through the help of some influential Turks, had remained behind and had assumed an administrative position in the Sis (Kozan) municipality, blames the French for the initiation of the Tesviye-i Mesalih Komisyoni (Brokerage for Settlement of [Property] Rights) courts. He writes in his memoirs that this court system was established to benefit Armenian “settlers” by confiscating Turkish lands and handing them over to Armenians without proper judicial procedures.[25] It must be noted, however, that the activities of the aforementioned court were limited to only a few hundred cases, not all of which were decided in favor of Armenian plaintiffs. Often, Armenians, because of their sudden and panicky deportation in 1915, had left everything behind and hence could not produce the proper Tapus (Tapu, Turkish for land deeds) to reclaim their properties. Moreover, if unjust acts of land confiscation had actually occurred, it is to be assumed that almost all such cases had to taken place near or around the major cities where French protection was provided, since no Armenian could have ventured to confiscate lands from Turks in the remote villages. In any case, Armenians did not have a free hand in confiscating Turkish properties, since the French administration, in its effort to reestablish law and order, would not allow them to do so. Moreover, Turkish peasants, encouraged by Kemalist agitators, disrupted the implementation of the orders of the arbitrating court. Dalkir and other Turkish sources do not mention the fact that after the deportation of the Armenians in 1915, the Turkish government had relocated some eight thousand Turkish muhajirs (refugees) from the Balkans and Russia into Cilicia and had allowed them to settle on Armenian properties.[26] It caused the French administration much hardship to send some of these families back to where they had come from, while the rest continued to dwell on their newly acquired properties

Suffice it to say that the French administration made special arrangements for all non-Cilician Armenians repatriating to Cilicia. These people, together with Cilicians from the remote villages of the province, were settled in tent towns in the provincial capital of Adana, which had an Armenian refugee population of sixty thousand.[27] Since the French administration was unable to resettle these people in their old villages, it had to shoulder the heavy economic burden of feeding and providing shelter for a refugee population numbering in the thousands.[28] The inability of the French to resettle these people strengthened the Kemalists who were encouraging Turkish peasants to hinder the resettlement of the Armenians.[29] Turkish sources maintain that the Turkish population defied the orders of the arbitrating court in such places as Kozan, Fekke, Kars-Pazar, and Harouniye. [30] Wherever the population was unable to accomplish this end, Turkish bandits roaming the plain completed the task. A case in point is an incident that took place in the village of Sheikh Murad near Adana, where Turkish chetes (guerrilla fighters) murdered several Armenian peasants in front of their families.[31] For Armenians, this and several similar incidents were sufficient to question the capability of the French administration to protect their lives. The cruelty of the Turkish bandits convinced Armenians that it was safer to remain as refugees in Adana rather than to venture in small, vulnerable numbers in the outlying villages.

The arbitrating court posed problems and created friction between Turks and Armenians in Deort-Yol, Hasan-Beyli, Harouniye, and other places.[32] The French were unable to calm the situation. It can be argued with certainty that the inability of the French to confront this issue was due mainly to the limited number of their forces in Cilicia. Therefore, Pierre Redan’s estimate that “the arbitrating court solved the problem (i.e. the land ownership issues) and contented both parties with their decisions” [33]cannot be readily accepted.

Another issue that damaged French prestige in Cilicia was the court’s decision to bring some Unionist (Committee of Union and Progress, CUP) perpetrators of the 1915 genocide to justice. This court turned out to be a complete failure. Presided over by an ex-Ittihadist judge and having a Greek as an inquisition officer, the court considered only a fraction of the cases brought before it by the French administration and Armenian organizations. After several months of interrogations and deliberations, not even one Turkish official was convicted.[34]

Kemalist cells and their development

Cilicia was the first Turkish territory that the Kemalists “liberated” from the Allied powers in their “War of Independence.” The paucity of French forces in Cilicia was one of the main reasons for the Kemalists to have the province in the forefront of their struggle for liberation. Besides, Cilicia was the only area under Allied occupation that had kept its Ottoman administration intact, operable, and willing to help Kemal in his struggle against the Allies. Cilicia was thus totally different from Syria, where all Ottoman functionaries were deposed and replaced by French or local officials.[35]

Nazim Bey, who was the Vali (governor) of the province when the British and the French occupied it, saw to it that during the few months that he remained in office (until September 1919) ex-Ittihadist and Kemalist propagandists had a free hand in disseminating their ideology within the Turkish population. It seems that the vali was not content with helping Turkish agitators. He was personally involved in the organization of a secret network of “Union and Progress” party cells in almost all the major cities and towns. One of his associates, Nehad Pasha, was even encouraged by the governor “to form Islamic organizations directed against the Christian population and the French Administration”.[36]

Turkish sources confirm that Ittihadist and Kemalist committees were active in Cilicia during the first months of the British occupation. Those committees were being nourished by such organizations as the Kilikia Mudafaa-i Hukuk Jemiyeti (Organization for the Defense of Kilikia’s Rights), which was formed in Constantinople by some Cilician Turks, who soon after dispatched some of their members to Cilicia.[37] Apparently, the committees were directed against the Allied occupiers. Turkish agitators tried hard to convince the Turkish population that only an armed struggle could liberate Cilicia from the French.

On 28 April, 1919, Colonel Bremond, head of the French administration in Cilicia, issued yet another crucial order demanding the population to hand over all weapons to the French authorities within twenty four hours.[38] The order was generated from Constantinople where General Allenby was on a short visit. Allenby’s fiat was conducted masterfully in the areas under British Rule including the Eastern Occupational zone (Marash, Aintab, and Kilis).[39]

Once again it was obvious that the order was directed against the Turks. In February 1919, the French administration had uncovered a secret plan that called upon the Turkish population to participate in riots and take up arms against the French administration. The French order was thus intended to disarm the Turks and lessen the possibility of any new uprising. As in the case of the April 6 order, this one too was not vigorously imposed, even though one Turkish author exaggerates by writing that “Turks were thus deprived even from carrying their hunting rifles,” or that “some of those who defied the order were punished by being drowned in the Sihun River.”[40]

Another issue that became a source of friction between the Turks and the French authorities in Cilicia was that of the French tricolor replacing the Ottoman flag. As an occupied area of the Ottoman Empire, Cilicia was to fly the flag of the victors, in this case, that of the French. However, the replacement of the flag was totally unacceptable to the Ittihadists and Kemalists whose agitators used the issue to stir up Turkish nationalist emotions against the French. Trouble came on March 18, 1919, on the occasion of the French High Commissioner’s visit to Cilicia. In preparing for Georges Picot’s official visit, the French Administration had decorated the main boulevards of Adana with thousands of French tricolors. In some places the Armenian tricolor, the banner of the newly established Armenian Republic in the Caucasus, was raised alongside the French insignia. According to Turkish sources, the raising of the French and especially the Armenian tricolors was an insult that the Turks could not tolerate. For Turks, the question was one of national honor. Encouraged by Ottoman officials, some Turks desperately tried to fly the Ottoman banner on all official buildings and schools. The French responded by apprehending some of the vandals and imprisoning them for short periods of time.[41]

The involvement of Turkish officials in anti-French activities was one of the delicate issues that faced the French in Cilicia. French authorities had virtually no control over the activities of the vali and the high-ranking Ottoman officials. The only instance in which the French authorities took a firm stand against the still operating Ottoman administration was immediately following the disturbances that took place in the beginning of February 1919. Some of the Turkish agitators arrested during the initial rioting in Adana confessed that an uprising of much greater magnitude was being prepared. Moreover, the French authorities uncovered the plan for a general armed resistance in which the complicity of the vali, Nazim Bey, and the commander of the gendarme force, Hashim Bey, was apparent. The French had reason to suppose that the two officials were organizing Turks and arming them to overthrow the French administration. Only when all evidence became clear were the French authorities able to ask to depose the vali. Nazim Bey handed in his resignation and was soon called to Constantinople. He was replaced by Jelal Bey, who continued his predecessor’s work and even surpassed him. As for Hashim Bey, he, as head of the gendarme force, was under French jurisdiction. As soon as the investigation was over, a warrant was issued for his arrest. He was apprehended and sent to serve his prison term in Syria, where he eventually died.[42]

General Leslie, a British officer who was at the time acting as the commander of the Allied occupation forces in Cilicia, appointed the French Captain Luppe as the new inspector-in-chief of the three thousand man gendarme force. The latter assumed his duties on April 24, 1919. His first task was to reduce the force to two thousand two hundred men by ousting all the suspicious elements that were involved in the uprising plan. Captain Luppe enlisted some five hundred Armenians and other Christians into the force.[43]

The mild French response to Turkish agitation coupled with the administration’s inability to implement sound policies created suspicions within the Armenians. Obviously, Armenians wanted more than what the French were able to deliver. The major setback in French-Armenian relations occurred towards the end of 1919, when the French High Commissioner in the Levant, Georges Picot, not only halted the process of Armenian repatriation to Cilicia, but he even ventured to travel to Ankara to meet with Kemal. Picot’s visit to Ankara–which he undertook upon completing his mission in the Levant–was a turning point in French policy toward Armenians in Cilicia. Moreover, Picot’s visit and the change in French attitudes regarding Armenians coincided with the presentation of the somewhat inflated Armenian demands to the Peace Conference in Paris.[44]

The Delegation of Integral Armenia, headed by Avetis Aharonian, representative of the Delegation of the Republic of Armenia, and Boghos Nubar Pasha, representative of the National Armenian Delegation, introduced an Armenian agenda to the Peace Conference, which stated, among other things, that Cilicia was to be made part of the Armenian state to be created by the Allies.[45] The Armenian demand of encompassing Cilicia in the future Armenian state was alarming to the French. It became a major consideration in the change of French policy towards Armenians in Cilicia. Picot, who at the beginning of 1919 had assured Armenians that he was doing everything in his power to encourage massive Armenian repatriation to Cilicia, declared after a few months that the repatriation process was an expensive venture that had cost the French treasury more than ninety million francs, and had to be halted because of insufficient funding.[46]

On leaving the Levant, Picot went to Ankara and met with Mustafa Kemal, the leader of the Turkish nationalist movement, who was fighting to oust the French from Cilicia. Picot’s visit was to clear obstacles against Franco-Turkish cooperation as was manifested in the signing of the Ankara Treaty in October 1921. Although some French sources emphasize the fact that in traveling to Ankara Picot was acting in accordance with the recommendation of the French government that was furious at Armenian demands concerning Cilicia, Bremond finds the visit contradictory to Allied and French policies in the Levant. He also states that Allied headquarters in Jerusalem and Constantinople criticized Picot’s meeting with Kemal.[47]

Picot’s visit damaged the prestige of the French administration in Cilicia. The Kemalists realized that French interest in the area was decreasing. Accordingly, Kemalist attacks on French occupation forces gained momentum during the period immediately after the visit. The last of the British forces left Cilicia in November 1919. The departure of the much-needed British regiments created new problems. The French High Commissariat in Beirut tried to remedy the situation by dispatching several companies under the command of General Dufieux to Cilicia. Upon arrival, Dufieux was named commander-in-chief of the French occupation forces in Cilicia. He assumed his duties on December 2, 1919.[48]

The arrival of General Dufieux coincided with that of the newly appointed vali, Jelal Bey, whom Constantinople had sent to replace the deposed governor, Nazim Bey. The new vali was an Ittihadist functionary whom Bremond describes as “intractably Francophobe.” [49] Jelal Bye not only neglected the existence of the French administration and encouraged local Turks to rebel against the occupation forces, but he was instrumental in strengthening and furthering the cause of anti-French groups.[50] Moreover, Jelal Bey’s appointment was contrary to the stipulations of the 1918 armistice in that Constantinople had designated him without asking for the consent of Allied headquarters.[51] Turkish historian Kasim Ener writes that, upon his arrival to Adana, Jelal Bey was greeted by a delegation comprised of Turkish eshraf (notables), Ittihadist leaders, and undercover Kemalists with whom he conferred for two days: “As soon as [Jelal Bey] arrived at Adana, he became a member of the Kemalist Party formed by the ex-deputy Subhi Pasha. Subhi Pasha and his brother, Kadri in Adana, Sadik Pasha in Tarsus and his son-in-law, Hakki Bey were against the French occupation of Cilicia . . . It so happened that Jelal Bey joined forces with these people.”[52]

Jelal Bey’s appointment coincided with Mustafa Kemal’s declaration of the illegality of the French occupation of Aintab and Marash.[53] In January 1920 Kemal ordered his troops to attack Marash. Although the local French garrison and the several French companies stationed there were able to halt the Kemalists, Colonel Norman, the commander of the French troops in Marash, for reasons that remain moot even today, ordered his troops to retreat from the city without first warning the Christian population.[54] Only half of the eight thousand Armenians were able to join the retreating French forces; Kemalist bands wiped out the rest.[55] The retreat from Marash to Osmaniye was a disaster because of the harsh winter of 1920. Hundreds of French soldiers and Armenian refugees froze to death, while the rest reached their destination exhausted.

French sources admit that the retreat of their forces from Marash was a shameful act of cowardice rather than a tactical, military move. Moreover, the retreat from Marash was a severe blow to the already fading French reputation in Cilicia.

From another perspective, the fall of Marash was a much needed victory for the Kemalists; it enabled them to win the support of Turkish peasants and even some Turkish elements that had previously opposed Kemal and his nationalistic policies. Mustafa Kemal was now ready to galvanize this popular support and accelerate his offensive. Two months later, in March, Kemalist forces besieged the Armenian stronghold of Hadjin. Meanwhile, in the Eastern occupation zone, some Kemalist units were fighting the French in Aintab. It was during these trying times that a twenty-day truce was signed on May 28, 1920.[56] The French agreed to hand over Aintab to the Kemalists, who, contrary to the provisions of the truce, tightened their grip over Hadjin and terrorized Armenians in Sis (Kozan) and the surrounding villages. Thousands of Armenians took refuge in Sis, from where they retreated with the French forces south of the Mersin-Osmaniye railway.

The fall of Marash, Aintab, and Sis, the siege of Hadjin, and the French retreat south of the Mersin-Osmaniye railway alerted Armenians in Adana to the gravity of their situation. Armenian fears grew even more when almost all of the Turkish population of Adana retreated north of the railway and joined forces with the Kemalists. Only when the situation had deteriorated beyond any repair did Armenians start to organize themselves in order to defend the capital city of Adana and its vicinity.[57]

From January to June 1920 the vali, Jelal Bey, continued to communicate freely with the Kemalists. He was able to inform them of the positions and movements of the retreating French forces.[58] The French administration even became aware that it was the governor who was spreading the rumor that the French were soon to evacuate Cilicia.[59] After the fall of Aintab, Jelal Bye tried to organize a similar Kemalist incursion and takeover in Adana. Nevertheless, the French had taken notice of his activities and took measures to prevent him.[60] The conspiring vali continued his intrigues for almost one more year. On May 17, 1921, the minister of interior, Reshad Effendy, recalled him to Constantinople.[61]

Four months later, in October 1921, the French finally gave in by signing the Ankara agreement with Kemal. [62] Cilicia was brought under Kemalist control while the French retreated south of the Alexandretta-Midan Ekbez-Kilis line. Armenians had to once again leave their ancestral homes and follow the retreating French troops.

* For the purpose of this article modern Turkish transliteration is utilized only in the footnotes. Personal, locale, and publications names are reproduced to give, as much as possible, the most exact phonetic rendition and yet make reading the text easier for English speaking people. It must be noted that the essay deals with a period in history where Ottoman rather than Modern Turkish was the language in use. Also, since all Armenian personal, locale, and publications names are Western Armenian, they have been phonetically reproduced as pronounced in that dialect. The Library of Congress Armenian transliteration system (based on Eastern Armenian phonetic values) is utilized in the text and footnotes to refer to names and sources that are Eastern Armenian.

[1]Robert Farrer Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922, Ph.D. dissertation (University of Utah, 1991), pp. 176-185. The French action was aimed at curbing American missionary initiatives to help Armenians resettle. This was crucial for France because of talks about an American mandate for Armenia that might also include Cilicia. With no special funds to be able to resettle Armenians, the French administration in Cilicia resorted to collecting taxes and thus meddling in what Zeidner calls the “internal affairs” of the province, thus alienating the Turkish population there.

[2] R[uben] K. Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere ev Kilikian 1919-1921T[vakannerun] (Turkish-French Relations and Cilicia, 1919-1921) (Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences Press, 1970), p. 40.

[3] Puzant Yeghiaian ed., Adanayi Hayots Patmutiun (History of Adana Armenians) (Antilias: Catholicosate of Cilicia Press, 1970), pp. 433-437. The agreement was initially signed between France, Britain, and Russia. In 1917 the Soviets disclosed its existence and made public the terms of this secret agreement, which stated that in the event of an Allied victory the Levant was to be divided into several zones of influence and occupation. Cilicia was to be incorporated into the French zone. After the October armistice, Britain, whose troops in the Levant far exceeded those of France, occupied Cilicia temporarily by stationing several British battalions there.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 226.

[6] Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922, pp. 132-141. The order to demobilize the Turkish Yildirim Army was entrusted to Mustafa Kemal As soon an he took over control of the army from the German Marshal, Liman Von Snders (whose officers were now on the run for their lives), Kemal started contesting the articles of the armistice, especially indicating to his superiors in Istanbul the general Allenby was adding new requirements to them. Finally, Kemal left for Istanbul and in turn entrusted the evacuation of the army units, officer cadres, and, more importantly, the huge amount of guns and munitions left over by the Germans, to his inferiors who attached some of the units to existing gendarme forces in Cilicia. [7] Recep Dalkir, Yigitlik Gunleri (Days of Heroism) (Istanbul: T.T. Postasi matbaasi, 1961), 14. See also:

Paul Du Veou, La Passion De La Cilicie, 1919-1922 (The Passion For Cilicia, 1919-1922) (Paris: Librerie Orientalist, 1954), p. 64.[8] Dalkir, Yigitlik Gunleri, p. 14.

[9] Edouard Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29 (Winter 1976-1977), p. 345.

[10] Ibid., 345.

[11] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 119.

[12] Dikran H. Boyadjian, Haygagan Lekeone, Badmagan Hushakrutiun (The Armenian Legion: A Historical Memoir) (Watertown: Baykar Press, 1965), pp. 190-191.

[13]Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29 (Winter 1976-1977), p. 365.

[14] Kasim Ener, Cukurova’nin Isgali Ve Kurtulus Savasi (Chukurova’s Occupation and Its War of Independence) (Istanbul: Berksoy Matbaasi, 1963), 23; Bremond, “The Bremond Mission,” p. 43.

[15]Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29 (Winter 1976-1977), 346.

[16] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p.120.

[17] Pierre Andre Redan, La Cilicie et le Problem Ottoman (Cilicia and the Ottoman Problem) (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1921), pp. 76-77.

[18] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 119.

[19] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920, The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 346.

[20] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 119.

[21] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920, The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 348.

[22] Du Veou, La Passion De La Cilicie, , p. 91; Sahakian, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 122.

23 Sh[mavon] T. Torossyan, Kilikiayi Hayeri Azgayin-Azatagrakan Sharzhumnere, 1919-1920 (The National-Liberation Movements of Cilician Armenians, 1919-1920) (Yerevan: 1987), p. 86.

24 Sh[mavon] T. Torossyan, Kilikiayi Hayeri Azgayin-Azatagrakan Sharzhumnere, 1919-1920 (The National-Liberation Movements of Cilician Armenians, 1919-1920) (Yerevan: Univ. of Yerevan Press, 1987), p. 86.

25 Dalkir, Yigitlik Gunleri, pp. 21, 41, 64.

26 Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 349.

[27] Ibid, p. 348; Torossyan, Kilikiayi Hayeri Azgayin, 95. French sources (Bremond, Du Veau, Redan) often speak about economic difficulties that Cilicia encountered and how these were temporarily remedied by payments from the French Exchequer. See also: Robert Farrer Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922, Ph.D. dissertation (University of Utah, 1991), 176-185. This is not what Zeidner tries to convey in his dissertation where he underlines the fact that France practically left Bremond on his own in terms of finding financial resources for Cilicia. It must be noted that the central Ottoman government too had promised to take care of repatriation. However, this could not be expected from an entity that was surviving through loans from the Allied powers and especially Britain.

[28] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920, The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 348.

[29] Dalkir, Yigitlik Gunleri, p. 67.

[30] Ibid., 65-66.

[31] Yeghiaian, Adanayi Hayots Patmutiun, p. 438.

[32] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 126.

[33] Redan, La Cilicie et le Problème Ottoman, p. 85.

[34] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 126.

[35] Edouard Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 30,

p. 35.

[36] Redan, La Cilicie et le Problem Ottoman, p. 78.

[37] Ener, Cukurova’nin Isgali, p.43. About the formation of the organization’s cells in Cilicia see: Dalkir, Yigitlik Gunleri, pp. 64-65.

[38] Ener, Cukurova’nin Isgali,, p. 20.[39] Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922, pp. 214-215.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Redan, La Cilicie et le Problem Ottoman, pp. 19-20. See also, Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 364.

[42] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 352. See also: Torossyan, Kilikiayi Hayeri Azgayin-Azatagrakan Sharzhumnere, p. 113. French and Armenian sources (and to some extent Turkish sources) mention that Hashim Bey, head of the gendarme forces, and Nazim Bey, the vali, were instrumental in planning the uprising in Adana in February 1919. They secretly encouraged Turks to smuggle arms into the city. The French administration, however, uncovered the plot.

[43] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 352. It is interesting to note that Zeidner calls this Armenian gendarme force a “militia.” Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922, pp. 216.[44] This had to do with the Armenian demand of the creation of an independent Armenian state incorporating Cilicia as was presented by the Joint Armenian delegation headed by Avetis Aharonian and Boghos Nubar Pasha. This demand was severely scrutinized in French political circles and the media. The rubric “l’Empire Arménienne” was often used sarcastically as a reference to an unfathomable Armenian demand.

[45] Torossyan, Kilikiayi Hayeri Azgayin-Azatagrakan Sharzhumnere, pp. 102-103.

[46] Ibid., pp. 96-97. According to the provisions of the Mudros armistice, the Ottoman government in Constantinople was liable to pay all expenses for Armenian repatriation to Cilicia (See Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 349). It seems, however, that after a marginal initial payment, the Turkish government neglected its duties in this regard. Consequently, the French High Commissariat in Beirut was burdened with the costs of transporting Armenians from Syria to Cilicia. Bremond also states that the repatriation of Armenians to Cilicia was halted in September 1919, when the French High Commissioner stopped paying money for that purpose. It must be assumed then, that Armenian repatriation to Cilicia after September 1919 was accomplished through sums allocated by Armenian and other humanitarian organizations.

[47] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 30 (Spring 1977), p. 35.

[48] Ibid., p. 34.

[49] Ibid., p. 35.

[50] Ener, Cukurova’nin Isgali, p. 27. Kasim Ener states that after his appointment, and while still in Istanbul, the new vali, Jelal Bey, had already written to Kemalist leaders in Cilicia and informed them of his future moves. Many Kemalists greeted the new vali at the station in Adana when he arrived there by train. According to Colonel Bremond, Jelal Bey, upon his arrival, pretended to be sick for two days during which he held extensive meetings with Turkish notables and Kemalist leaders. Bremond, “The Bremond Mission,” vol. 30, p. 40.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ener, Cukurova’nin Isgali, p. 28.

[53] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920, The Armenian Review, vol. 30, p. 36.

[54] Ibid., p. 38. Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922, pp. 340-350. The French kept their withdrawal secret even from the American missionaries stationed in the city.

[55] Zeidner, The Tricolor Over the Taurus: The French in Cilicia and Vicinity, 1918-1922, p. 250. According to Zeidner 5,000 Armenians were able to flee with the retreating French forces.

[56] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 30, pp. 38-39. In fact, it was after the fall of Marash; the intense pressure by the Kemalists on Bozanti; the initial skirmishes in Aintab; and the first abandonment of that city that the 20 days truce of May 28 was signed between the French and the Kemalists. The truce was signed to save the French detachment in Bozanti. Bremond, however, argues (Bremond, “The Bremond Mission,” vol. 30, p. 47) that this goal was never achieved since Bozanti fell to the Kemalists anyway. Moreover, the truce alienated those Turks that opposed Kemal who put their faith in the French occupation forces. “Now,” states Bremond, “they [the anti-Kemalist Turks] found themselves obliged to rally to Kemalism”. Kemal did not honor the truce. In Colonel Bremond’s opinion, the twenty days were enough for him to reorganize his forces and start a new offensive. On the other hand, Turkish sources regard the May 28 truce as a tactical move on the part of the French. Kasim Ener, for example, states, that it was because of this truce that the French and Armenians had the time to evacuate Is (Koran) and to organize their defenses in and around Adana. Ener, op. cit., p. 71.

[57] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 30, p. 44.

[58] Ener, Cukurova’nin Isgali, p. 49.

[59] Ibid., p. 37.

[60] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 30, p. 43.

[61] Ibid., p. 46.

[62] Sahakyan, Turk Fransiakan Haraberutyunnere, p. 226.