Social and Political Life

Cilicia Under French Mandate , 1918-1921

Related Topics

[INTRODUCTION and THE FRENCH ADMINISTRATION]

[THE ARMENIAN LEGION]

[ECONOMY AND HEALTH CARE]

[SOCIAL AND POLITICAL LIFE]

[THE THORNY ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE and CONCLUSION]

Social and Political Life

In a matter of months after the establishment of the French Civil Administration in Cilicia Armenian social and political institutions were reorganized. Armenian benevolent organizations reopened schools. French, Swiss, and American missionaries reestablished their schools and administered several orphanages that sheltered thousands of orphans.

On the political scene, perhaps the most important achievement of Armenians in Cilicia during this period was the formation of the Armenian National Union. This central body acted as an unofficial Armenian government. It included representatives from the three Armenian religious denominations as well as the four Armenian political parties. Despite the strong competition among the political parties and the cultural, educational, and social committees that each had distinctly formed, the uniqueness of the circumstances and the experience of the previous years necessitated a strong sense of unity. The political parties and the church worked hand in hand with the French administration. [1]

Before being dispatched to Cilicia, Damadian was instrumental in galvanizing worldwide moral and financial support for the formation of the Armenian Legion. While in Cilicia, Damadian not only regulated relations between Armenians and the French administration, but became the motivating force behind the social, cultural, and educational achievements of the community. He worked relentlessly to generate solidarity among the competing Armenian political parties.[2]

The newly created Armenian National Union in Adana formed special educational committees and entrusted them with the task of facilitating the reopening of schools as soon as possible. During 1919-1921 a total of seventeen schools resumed operation in the city of Adana alone. [3] Of these, the Armenian prelacy administered seven, four were reestablished by the other Armenian denominations, and six were missionary schools.[4]

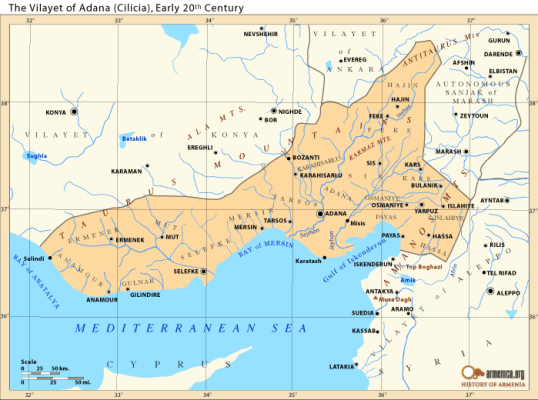

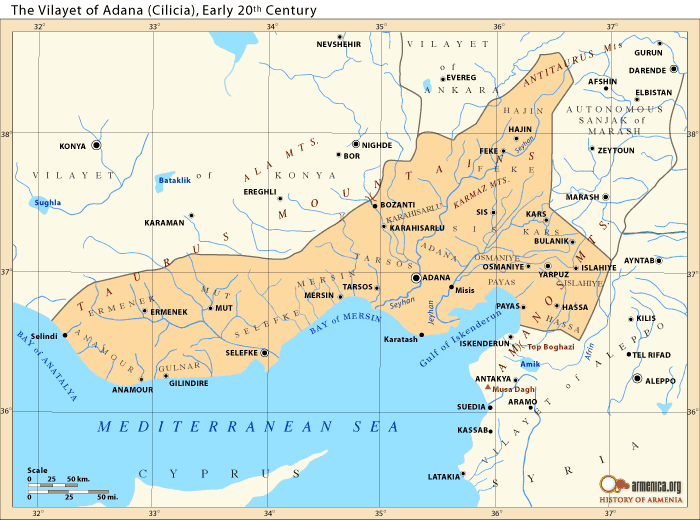

Although it is hard to find similar statistics for other cities in Cilicia, it is clear that schools opened in Mersin, Tarsus, Deort-Yol, Osmaniye, Alexandretta, and elsewhere. The French administration allocated sums that were necessary to reopen all prewar French missionary schools. Moreover, a special order from the office of the chief-of-administration stated that the teaching of the French language was to be mandatory in all schools.[5]

Many Turkish schools also benefited from the peace and welcomed students. Turkish schools, however, had not suffered as much as Armenian and other Christian schools. Turkish educational institutions had practically operated on a regular basis during the war and were only closed for a short period during 1918. Armenian schools, however, were closed for the entire war and resumed their duties only in 1919. Several years of neglect had brought costly damage to the buildings that needed huge sums to rebuilt and renovate. The French administration was helpful in this regard. It allocated sums to revive not only Armenian and other Christian schools (Greek, Arab) but Turkish ones as well. [6] Some twelve thousand Armenian students were registered at schools operating through the efforts of the Armenian community. [7]

Armenian orphanages provided shelter and served as educational institutions. During the war, Armenian children in Cilicia had had a higher chance of survival than their counterparts in historical Armenia. Many had been taken away from their parents just before the deportations and handed over to Turkish families who raised them as Turks. Others were put in special orphanages in Mersin, Urfa, and Aleppo.[8] Therefore, one of the most urgent tasks for repatriating Armenians in 1919 was to locate and liberate Armenian orphans. Swiss and American missionaries buttressed Armenian efforts. Yet it was the London-based Lord Mayor’s Fund, which actually assured the task of providing the orphanages with sums necessary for maintenance. [9] During the first six months of 1919, Armenian orphanages were established in Adana, Sis (Kozan), Hadjin, Deort-Yol, Osmaniye, Harouniye, Tarsus, Mersin, Marash, and Aintab. The total number of orphans admitted was more than ten thousand.[10]

Inter-party rivalry within the Armenian community was spreading even in the school system and was causing friction between students in the upper classes. This obliged the Special Educational Committee (formed by the Armenian National Union for the purpose of organizing education in Cilicia) to initiate counter-propaganda in the local Armenian Newspapers to assert that Armenian schools in Cilicia were academic institutions and not podiums for political parties to propagate their ideology or policy positions. [11]

The issue of teacher salaries was one of the major problems the Educational Committee had to face. The minutes of the committee show that complaints presented by teachers and salary related issues in general were a permanent topic on the agenda. During the 1919-20 scholastic years–the last for Armenian students in Cilicia–the seven Armenian schools in Adana operating under the guidance of the Armenian Prelacy hired a total of 65 teachers whose annual salaries ranged from 222 to 1,000 Turkish pounds. The annual budget for teacher pay was estimated at 35,000 Turkish pounds. During the same scholastic year, the operational budget of the committee was estimated at 5,500 Turkish gold coins or 32,250 Turkish pounds (5.5 Turkish pounds = one Turkish gold coin).[12] The Educational Committee had to find other sources–such as sums allocated by the French administration or Armenian benevolent organizations abroad–to balance the deficit, since it was unable to ask for tuition from the 2,176 students admitted to the above mentioned seven schools.

According to official statistics published by the French administration in Cilicia, six Turkish schools operated in Adana alone during 1919-20. There were 49 educators teaching the 687 students attending these schools.[13] The other Christian communities (Greeks, Syrians and Maronites) had six schools operating with twenty teachers and 655 students. The six Missionary schools had forty-seven teachers, most of them missionaries, and a collective student body of 711 students. [14]

Organizations and the Press

The issues of Davros impart the message that there was a conscious effort on the part of Armenians to promote their culture and social life in all ways possible. Numerous theatrical performances, public lectures, and musical recitals highlighted Armenian cultural life. The three reestablished presses in Adana and Mersin published periodicals, newspapers and even books. [15]

It seems though that this tempered renaissance in education, culture, and political awareness was a product of the competition between the Armenian political parties, which tried to win over Armenians through political rallies and lectures that dealt with the political issues of the day such as the French occupation of Cilicia, the possibility of establishing an autonomous Armenian entity under French mandate, or an American mandate. The Armenian parties competed with each other not only in the sphere of politics, but even in the cultural and social realms by establishing their own cultural organizations and Armenian Red Cross committees for social work. The latter was the medium through which Armenian women participated in the reorganization of the community.

Aside from the party-oriented socio-cultural structures, there were at least a dozen other cultural or social organizations operating in Adana that had their branches in other cities as well. [16] Important among these in terms of membership and activity were the Youth Organization of Adana (Adanayi Yeritasartats Miutiun), Young Men’s Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.) that organized night adult schools for instruction in French and English, The Union of Armenian Legionaries (Hay Lekeonaganneru Miutiun) which had its organ, Arara.[17] There were also several compatriotic unions functioning in Adana such as those of Hadjin, Sis, Dikranagert, and Gesaria.[18]

Four Armenian political parties had regional central committees in Adana, where regional party organs were published. These were: 1- The Social Democratic Hnchakian Party (Sotsial Demokrat Hunchakian Gusagtsutiun) with branches and committees in the other cities of the plain. Davros, its organ from 1919 to 1920, was first edited by attorney Firuz Khanzadian and then by Antranig Genjian. In 1921, the party started publishing Nor Serunt (New Generation) as its official organ. The party had cultural, athletic, as well as student and youth committees. It initiated the Hunchakian Women Auxiliary (Hunchakian Ganants Miutiun), which acted as the party’s Red Cross chapter for social work, especially in the camps and tent cities in Adana; 2- The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Hay Heghapokhagan Dashnaktsutiun), which expanded in the same pattern as the Hnchakian Party. Giligia, edited by Central Committee member Minas Veradzin, was the official organ of the party. It appeared uninterruptedly from 1919 to 1921; 3- The Reformed Hunchakian Party (Veragazmial Hnchakian Gusagtsutiun) with Giligian Surhantag (Cilician Courier) as its official organ; 4- The Armenian Constitutional Democratic Party (Hay Sahmanatragan Ramgavar Gusagtsutiun) with Hay Tsain (Armenian voice) as its official organ. [19]

The central committees of the four Armenian political parties formed an inter-party council that worked in conjunction with the Armenian National Union. In general, the role of the Armenian political parties in Cilicia during 1919-21 was organizational.[20] All four worked to normalize conditions for a productive Armenian communal life. Party newspapers ran politically oriented editorials, articles in which the idea of Cilician autonomy was strongly defended and the change in French policy emphatically criticized. Yet the political activities of the Armenian parties never passed beyond the limits of the written word, although Turkish sources speak of Armenian Komitajis (revolutionaries) who terrorized Turkish villages. The weakness of Armenian parties in Cilicia must be attributed to the fact that these were organizations that had themselves repatriated to Cilicia in 1919 and had to start anew. Although they had their input in advising Armenians about the political issues of the day and also made them aware of the gradually fermenting idea of an autonomous Cilicia, overall, their role remained marginal in the events that were to shape Cilicia’s fate.[21]

Between 1919 and 1921, several non-partisan Armenian newspapers and periodicals were published in Cilicia. Most important among these were: 1- Arara, the organ of the Union of Armenian Legionaries. Haik Mosdikian financed it. Keghard-Shara was its editor; 2- Nor Ashkharh (New World) owned by Matios Yeretsian. Only few issues were published; 3- Adana, which appeared in July 1920. Parsegh Shaljian and Hovhannes Ammikian were the owners and editors. The newspaper offered its readers a Turkish-language supplement written in Armenian characters; 4- Hay Tsav (Armenian Pain) first published in 1920. Setrak Gebenlian was the owner and editor; 5- Lampron, named after the famous medieval Armenian castle, was published in Tarsus. It was the organ of the Armenian Students’ Association of St. Paul’s College, operated by American missionaries and managed by Dr. Christiel. Dr. Nishanian was the editor.

Newspapers with limited circulation appeared for short periods of time in Deort-Yol (Sisvan, published in 1920), Anitab (Sharzhum, the organ of the Hnchakian Student Association in the city), and Marash (Rahvira Mentor, a bilingual published in Armenian and Turkish). Several Turkish newspapers were published in Cilicia during 1919-21 as well.[22]

The Armenian newspapers published in Cilicia devoted their pages to articles dealing with social, political, and cultural aspects of Armenian communal life. Topics ranged from complex political matters such as relations with the French administration or analysis concerning Cilicia’s future and the Peace Conference in Paris to statistical reports about schools, social and cultural events, and conditions relating to the Armenian refugee population in Adana and the other cities (especially when thousands of new refugees were brought from Marash and Sis due to the retreat of the French forces to the south of the Mersin-Osmaniye railway line as a result of the 28 May, 1920 truce with the Kemalists).

The French administration, however, implemented a strong policy of censorship on Armenian as well as Turkish newspapers in Cilicia during 1919-21.

[1] Ibid., p. 460.

[2] Mihran Damadian, Im Husheres (From My Memoirs) (Beirut: Zartonk Press, 1985), p. 142.

[3] Yeghiayan, Adanayi Hayots Badmutiun, p. 650.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Bremond, “The Bremond Mission, Cilicia in 1919-1920,” The Armenian Review, vol. 29, p. 354.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Yeghiayan, Zhamanakakits Badmutiun Gatoghigosutian Hayots Giligio, 1914-1972, (Contemporary History of the Catholicosate of Armenians of Cilicia, 1914-1972) (Antilias: Catholicosate of Cilicia Press, , 1975), p. 97.

[9] Ibid., p. 98.

[10] Ibid., pp. 98-99.

[11] Yeghiaian, Adanayi Hayots Badmutiun, p. 689.

[12] Ibid., pp. 699-706.

[13] Ibid., pp. 654-655.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., p. 712. Four of the existing six publishing houses belonged to political parties. Two were private (one in Adana and the other in Mersin).

[16] Ibid., p. 710.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Haydararutiun” (Announcement), Davros (Adana, November 27,1920), p. 2.

[19] Yeghiayan, Adanayi Hayots Badmutiun, pp. 709-712.

[20] Ibid., p. 712.

[21] Ibid., p. 711.

[22] Damad Arikoglu, Hatiralarim (My Memoirs) (Istanbul: Tan Matbaasi, 1961), pp. 172-173. Those were: 1- Ferda (The Future, Tomorrow), owned and edited by Ali Hilmi Bey, an anti-Ittihadist Turkish liberal who was a member of the prewar Turkish I’tilaf (Mutual Agreement) Party: 2- Adana Postasi (The Adana Post) owned by Huseyin Ilham Pasha: 3- Rehber (The Guide) owned and edited by Istanbullizadeh Yusuf. When pro-Kemalist Turkish notables and agitators left Adana for Bozanti after it was taken over by Kemal, a Turkish press was established and the newspaper Yeni Adana (New Adana) was published. This Kemalist pamphlet was secretly distributed among Turks in Adana. It ran articles and news items that described imaginary Kemalist victories. The militant editors of Yeni Adana wrote in a distinct nationalistic tone, often inciting Turks against the French and Armenians. Le Courier d’Adana, on the other hand, was the only French newspaper published in Cilicia during 1919-1921.