Origins and Identity of Hayasa

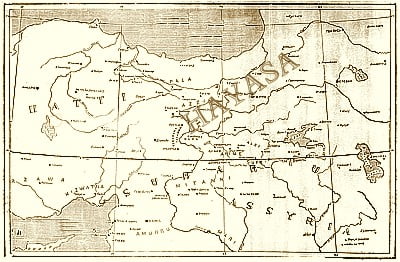

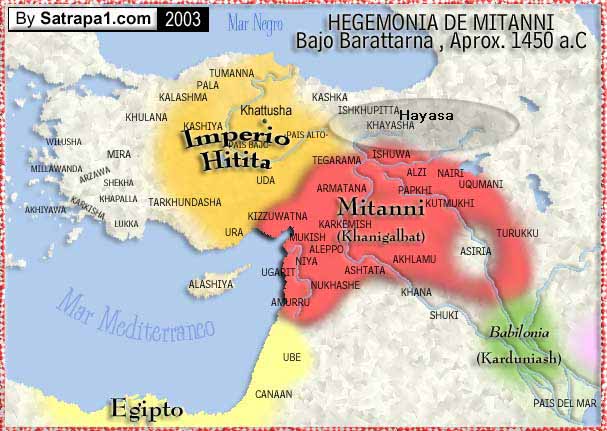

Hayasa (Hayasa-Azzi), a mountainous kingdom near Lake Van, is mentioned in Hittite records dating back to the 14th century B.C. It is often associated with early Armenian identity, possibly linked to Hayk, the legendary patriarch of the Armenians. The name Hayasa is considered by some scholars to be an early form of “Hayastan” (Armenia). The Greeks also referred to this region in their writings about the Armenians. Cuneiform tablets from Boghaz Keuy list four successive kings of Hayasa—Karannish, Mariyash, Hukkanash, and Anniyash—who ruled between 1390 and 1335 B.C.

Kings and Conflicts with the Hittite Empire

Karannish led incursions into the Hittite empire but was repelled by Emperors Dudhaliyash and Subbiluliuma. Mariyash married a Hittite princess but was executed for breaching the marriage treaty. His successor, Hukkanash, also married a Hittite royal, and the treaty included stipulations highlighting legal and cultural differences. For instance, the Hittite king warned him not to marry his sisters-in-law or cousins, customs deemed uncivilized by Hittite standards.

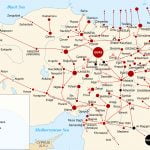

Hukkanash remained politically assertive, demanding the return of Hayasan prisoners before releasing Hittite captives. The Hittite Empire often faced incursions from the east—Aravanna (modern Yerevan), Tebruzzi (Tabriz), and Hayasa-Azzi. Anniyash formed a union of Armenian tribes, extending his kingdom from the River Iris (Yeşilırmak) to Lake Van. Eventually, in 1340 B.C., Mursili II launched a military campaign, crossed the Euphrates, and fought the Hayasans near Ingalova.

Decline, Resistance, and Historical Legacy

Despite temporary setbacks, Hayasa’s resistance persisted. The Annals of Mursil recount battles and sieges involving tens of thousands of troops. Mursili’s campaigns inflicted significant losses on Hayasa, which was no longer seen as a major threat by 1340 B.C. Still, after Mursili’s death in 1320 B.C., the Hittite Empire weakened under internal and external pressures.

Natural disasters, epidemics, and invasions—including by the Kaskas, whom some scholars link to early Armenians—further destabilized Hatti. The Kaskas advanced to the Hittite capital and forced the king to relocate religious relics. Historian Leonard King described the Kaskas as an “unruly people” from between the Euphrates and Lake Van, against whom no Hittite king could secure lasting control. This suggests that Hayasa’s cultural and geopolitical influence continued, even as the Hittite Empire declined and the Assyrians expanded their dominance in the region.