Armenian medicine, which has a history of some 3000 years, has created a rich treasury of natural medicaments. Medicine is an inseparable part of ancient Armenian culture and its roots come from deep in the past. Relying on folk medicine and its sources, it accumulated the experience and knowledge of many generations of Armenian physicians on the curative properties of plants and animals as well as minerals.

In ancient times, the medicinal herbs of the Armenian highland were especially well-reputed. Those herbs were exported to the East and to some countries of the West. Thus such ancient and Arabian writers as Herodotus, Strabo, Xenophanes, Tacitus, Pliny the Elder, Dioscorides. Galen, Ibn Sina and al-Biruni, when discussing Armenia, also mentioned its natural medicinal plants. Armenian historians Movses Khorenatsi, Pavstos Buzand, Lazar Parpetsi, Thovma Ardsruni gave much important information on medicine in ancient Armenia. The medicinal plants of Armenia were grown with great care in special gardens founded as early as those on the initiative of king Vagharshak (2nd cent. B.C) and Artashes (1st cent. A.D.). The remarkable curative hormonic properties of certain plants, as for example, the white bryony (Bryonia alba) and the black cumin (Nigella sativa) brought about the worship of these plants in Armenia, ancient expressions of which have been preserved in Armenian folklore.

In ancient times, such mineral medicaments as Armenian clay, Armenian stone, Armenian salpetre and soda were in great repute, as were compounds of mercury, iron, zinc and lead, all exported to neighbouring countries. In addition to mediicinal plants and minerals, Armenian medicine also made use of medicaments of animal origin, prepared from the organs and tissues of animals, some of which were endowed with fermentative properties. Among the latter were extracts of endocrine glands, brain, spleen, liver, the bile of certain animals, the rennet of the rabbit as well as the “moist zufa”, a plant-animal mixed compound. The above-mentioned medicaments were endowed with antitoxic, stimulating, hormonic, antisclerotic, antiseptic, antitumoural properties, which are of great value for modern medicine.

At the beginning of its development, Armenian classical medicine bore the beneficial mark of Hellenistic culture. The works of ancient writers such as Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, Asclepiades and others, translated into Armenian through the efforts of representatives of the Philhellenic School of translators, had a great influence upon the outlok of medieval Armenian physicians.

Armenian physicians of the Middle Ages seriously studied the classical works of ancient medicine and used that viewpoint as a basic for scrutinizing the achievments of folk medicine. In medieval Armenian science, the ancient theory of the four elements (earth, water, air, fire) and their corresponding four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile) first appeared in the work of Yeznik Koghbatsi “Denial of Heresy”. He connected the appearance of illnesses with a disruption in the balance of the basic humours. However, in addition to the four humours, Yeznik took into consideration the influence of external factors.

Davit Anhaght (the Invincible), the famous Armenian philosopher of the Middle Ages (end of the 5th and beginning of the 6th centuries) was well acquainted with the Hippocratic principles of medicine. In his work “Definitions of Philosophy” Anhaght discusses questions of anatomy, biology, pharmacology, pathology and especially of medical ethics in the spirit of Hippocrates’ “Oath”. Anania Shirakatsi (7th c.), the eminent Armenian astronomer and philosopher, was greatly interested in theoretical and practical problems of medicine. In his “Knnikon”(Canon) he encluded medical works along with those on astronomy, mathematics, chronology and philosophy.

Especially favorable conditions for the development of art, science and medicine in particular, were created in the epoch of Armenian Renaissance (10-14th centuries), during the rule of the Bagratuni family in Ani and Rubenid-Hetumid kings in Cilicia. Schools of higher education or medieval universities were founded in Ani, Haghpat, Sanahin and Sis, where along with philosophy and natural sciences, medicine was also a subject of study. Hovhannes Sarkavag (1045-1129) who lectured at the Ani and Haghpat schools of higher education, expressing the tendencies of that time, advocated the separation of sciences from religion and the necessity for the experimental study of nature. These ideas of the great Armenian philosopher preceded those of representatives of the European Renaissance.

The medical conceptions of Ani school are reflected rather completely in the works of Grigor Magistros, a contemporary of Ibn Sina. A scholar, well acquainted with ancient culture in all its various aspects and being an erudite, he displayed his abilities in different branches of Armenian culture. Grigor Magistros Pahlavuni was not only fascinated by theoretical questions on medicine, he was also a skilled practical physician. In his “Letters” we see Grigor Magistros as an experienced physician with fine professional sensitivity, well-versed in pathology, clinical medicine and especially in phytotherapy.

It was in Ani, during the peak of the Bagratuni rule, that original studies on problems of pathology, therapy and pharmacology, so called “bzheshkaran’s” (medical books) first appeared. Unfortunately time has not preserved for us the author’s name of the famous “Bzheshkaran” which was written during the rule of the victorious king Gagik (990-1020) of the Ani Bagratuni dynasty. Later it was edited in Cilician Armenia and was called “Gagik-Hetumian bzheshkaran”.

The fruitful scientific and medical activities of Mekhitar Heratsi were connected with Cilician Armenia and the medical school there. He was the founder of medieval Armenian medicine. He played the same role in Armenian medicine as Hippocrates did for Greek, Galen for Roman and Ibn Sina for Arab medicine. He gathered, studied and deduced from the experience of the past in classical as well as folk medicine, creating such works as have not lost their value even today. In his masterpiece “Consolation of Fevers”(1184) discussing aetiological factors of infectious diseases, Heratsi introduced the theory of “mouldiness”. In his opinion, it is the mould in the blood and other body liquids , which brings about “mould” fever. From all ideas of premicrobiological period this theory is most closely related to the modern views. Armed with such knowledge, Heratsi used the experimental approach, often contrary to the scholastic point of view, and developed a complex system of cure based on the use of medicaments, especialliy herbs, as well as dietetic, physical methods and psychothrapy. All this truly places the Armenian great bzheshkapet among the first ranks of medieval physicians. Heratsi’s theory of “mouldiness” was developed by Cilician physicians. Among them were Grigoris, the author of “Analysis of the Nature of Man and his Ailments” and Stepanos, the son of Aharon, the author of “Dsaghik”(1232).

During the 13-14th centuries, there was a noticeable increase in activities in the schools of higher education in historical Armenia. The fundamentals of natural sciences and medicine were taught in Yerznka, Gladzor and Tatev, large scientific centres with ancient traditions. Of the medieval Armenian schools of higher education, the Tatev school is worthy of special mention, where the greatest thinker of that time Grigor Tatevatsi was active. In his “Book of Questions” the author’s ideas on human anatomy, biology, psychology and embriology were expressed.

After the downfall of the kingdom of Cilician Armenia at the end of the 14th century, the classical traditions in medicine were preserved in only a few cultural centres in Armenia, the last brilliant spark of which was the works of Amirdovlat Amasiatsi in the 15th century. In his books “Usefulness of Medicine” (1469),”Akhrapatin” (1459, 1481), “Useless for Ignorants” (1482) and other works he summarized the knowledge of medieval Armenian physicians on theoretical and practical questions.

A study of “Useless for Ignorants” by modern physicians makes it possible to become acquainted with the medicaments of Armenian medicine in the Middle Ages, and first of all with phytotherapy which was its main field. By means of experimental methods, the Armenian “bzheshkapet” revealed the antitumoural, tonus-raising, antitoxic and antisclerotic properties of some herbs and their gums (hog’s fennel, field eryngo, periwinkle, heliotrope, meadow saffron, snake bryony, birth-wort, galbanum, sagapenum etc.). These data presents great interest for modern medicine.

Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s traditions had a very definite influence on representatives of the Armenian medical school of Sebastia, whose physicians (Asar Sebastatsi, Buniat Sebastatsi and others) besides creating their own works, paid great attention to editing and interpreting Amirdovlat’s books. With the physicians of the Sebastian school (16-17th c.) ends the last period in the development of medieval Armenian medicine. However Amirdovlat’s traditions left a deep impression on the works of prominent physicians of the 18th century Petros Kalantarian and Stepanos Shahrimanian.Thus the reach experience of Armenian folk and classical medicine has not only pure historical significance but it also presents practical values in treating a number of diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis, psychical disturbances and allergies, problems which have not as yet been solved by modern science.

Medicine is an inseparable part of ancient Armenian culture. Its roots come from deep in the past. Relying in folk medicine and its sources, it accumulated the experience and knowledge of many generations of Armenian physicians on the curative properties of plants and animals as well as minerals.

Pagan Armenians worshipped Astghik, the goddess of love and beauty, and Anahit, the goddess of chastity and virtue, as patrons of medicine. According to Agathangelos and Movses Khorenatsi (5th c.), the temples of these goddesses were built in such picturesque sites of ancient Armenia as the provinces of Upper Armenia, Ayrarat, Taron and Vaspurakan. The priests at those temples were able to help sick people as they had learned from folk medicine and thus mastered the art.

In 301 Christianity became the state religion of Armenia. Monasteries were founded at the ancient pagan temples where the first hospitals were set up. According to Armenian historians Pavstos Buzand (5th c.) and Movses Khorenatsi Catholicos Nerses the Great had homes built for lepers, invalids and the insane, in different parts of historical Armenia. Hospitals existed in Armenia as early as the 3rd century. In 260, for example, Aghvita, the wife of the Armenian feudal lord (nakharar) Suren Salahuni, donated her own means to have a home for lepers built at the Arbenut curative mineral waters. It must be mentioned that in Europe the first home for lepers was founded some three hundred years later.

Armenian folk medicine, which has a history of some 3000 years, has created a rich treasury of medicaments. In ancient times, the medicinal herbs of the Armenian highland were especially well-reputed. Those herbs were exported to the East and to some countries of the West. Such ancient writers as Herodotus, Strabo, Xenophanes, Tacitus, Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides, when discussing Armenia, also mentioned its natural medicaments. [Fig.1]

Armenian historians gave much important information on medicine in ancient Armenia. Movses Khorenatsi, the father of Armenian historiography, wrote that king Vagharshak (2nd c. B.C.) founded orchards and flower gardens in the swamps of Tayk and Kogh. According to Thovma Ardsruni, the medicinal plants of Armenia were grown with great care in special gardens founded as early as those on the initiative of King Artashes (1st c. A.D.) about the fortress in the town of Artamet. According to Lazar Parpetsi, “there are in the valley of Ararat various roots of plants, which are used by skilled physicians to prepare quickly-curing plasters and liquid medicines for internal use in treating those who have long suffered from diseases”. The remarkable curative hormonic properties of certain plants, as for example, the snake bryony (Bryonia L.), black cumin (Nigella L.) and campion (Lychnis L.) brought about the worship of these plants in Armenia, ancient expressions of which have been preserved in Armenian folklore. [Fig.2]

In ancient times, such mineral medicaments as Armenian clay, Armenian stone and Armenian salpetre and soda were in great repute, as were compounds of mercury, iron, zinc and lead. Armenian clay (Bolus Armena) containing aluminium silicates and iron oxide was used in the treatment of inflammations, allergy and tumours. The clay was known to Galen and Ibn Sina who wrote in his Canon: “Armenian or Ani clay has a remarkable influence on wounds. It is especially beneficial against tuberculosis and the plague. Many people were saved during great epidemics since they were in the habit of drinking it in wine diluted with water”.

In addition to medicinal plants and minerals, Armenian medicine also made use of drugs of animal origin, prepared from the organs and tissues of animals, some of which were endowed with fermentative properties. Among the latter were extracts of endocrine glands, brain, liver, the bile of certain animals, the rennet of the rabbit as well as the “moist zufa”, a plant-animal mixed compound of which Ibn Sina wrote in his “Canon”, “That is the fat (lanolin) which in Armenia collects on the wool of the fatty tail of sheep dragged over spurge (Euphorbia L.). It absorbs the strength and milky juice of plants. Sometimes this fat is not thick and therefore it is cooked till it thickens. That fat wears away hard tumours and straightens bent bines when applied on a bandage”.The above-mentioned medicaments which are endowed with antitoxic, antisclerotic and hormonic properties present great interest for modern medicine. Thus, this valuable experience of folk medicine became later an endless source of development and enrichment for Armenian classical medicine.

In the beginning of the 5th century (404-405), Mesrop Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet, thus laying the foundation for Armenian chronology. Works on biology and medicine along with historical-philosophical treatises, occupy a valued place in medieval Armenian literature.

At the beginning of its development, Armenian classical medicine bore the beneficial mark of Hellenistic culture. The works of ancient writers such as Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen, Asclepiades and others, translated into Armenian through the efforts of representatives of the Philhellenic school of translators, had a great influence upon the outlook of medieval Armenian physicians. Among these works, Plato’s “Timaeus” deserves special attention, in which the author tried to explain not only the laws of the universe (macrocosmos) but also that of the origin and development of man (microcosmos). From the Greek translations of the early epoch the “Galen’s Dictionary”, “On the Nature of Man” by Nemesius of Emesa, “Anatomy” by Gregory of Nyssa , as well as the fragments of the works of Asclepiades, Democrates and Oreibasios have been preserved. [Fig.3]

Armenian physicians of the Middle Ages seriously studied the classical works of ancient medicine and used that viewpoint as a basic for scrutinizing the achievements of folk medicine. However, in Armenia, the writing of original medical works was late in fruition because of the Arab invasions, which resulted in a general decline in Armenian culture during the 8-9th centuries. It was not till the 10th century that the first “Bzheshkaran”s (Medical books) devoted to questons pertaining to the treatment of illnesses where besides the Greek influence, that of Arab culture was felt.

In medieval Armenian science, the ancient theory of the four elements and their corresponding four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile) first appeared in the “Denial of Heresy” by Yeznik Koghbatsi (380-450). He connected the appearance of illnesses with a disruption in the balance of the basic humours. “There are illnesses”, he wrote, “which come about not because of sins but because of an unbalanced nature of humours. Since man’s body is composed of four elements… and thus if any one of them increases or decreases, the result is illness”. However, in addition to the four humours, Yeznik took into consideration the influence of external factors, “to eat without consideration and in excess, to drink, to abstain severely, to work in excessive hot and cold weather and other conditions bad for the health”. He considered these factors of great significance in bringing about psychical and neurotic illnesses. Like Hippocrates, who rejected the “holy” nature of epilepsy, he too considered psychical illnesses the result of exhaustion of the brain. “As a result of exhaustion of the brain”, he wrote,” man loses his consciousness, he speaks to the walls, argues with the wind. For that reason physicians insist that it is not the devil that enters man’s body, those are illnesses of man which they can cure”. Born in Ayrarat and knowing the properties of Armenian herbs extremely well, their doses and synergic action in medicaments, he wrote, “Hemlock itself is a fatal poison under certain conditions, yet physicians use it to cure chronic diseases of the gall bladder. One sort of spurge, taken by itself, is poisonous, but when combined with other medicaments, it cures diseases of the gall-bladder and saves the patient from death”.

Davit Anhaght (the Invincible), the famous Armenian philosopher of the Middle Ages (end of 5th and beginning of the 6th centuries) was well acquainted with the principles of Hippocratic medicine. In his works “Definitions of Philosophy”, “Analysis of Introduction of Porphyry”, “Commentary on Aristotle’s Analysis”, Anhaght discusses questions of anatomy, biology, pharmacology, hygiene and medical ethics. Being very well acquainted with the practice of dissections on man and animals in the medical school of Alexandria, he wrote:”The function of analysis is to separate a substance into the parts of which it is composed, as for example, when one takes the body of a man, dissects the feet, hands, head and then separates the body into bones, muscles, blood vessels and nerves”.

Anania Shirakatsi (7th c.), the eminent Armenian astronomer and philosopher, was likewise greatly interested in medicine. In his “Knnikon (Canon), compiled in 667, he included medical works along with those on astronomy, mathematics, chronology and philosophy. That Anania Shirakasi worked on questions pertaining to phytotherapy is mentioned in codex 549 of the Mashtots Madenadaran, in which the curative and harmful properties of “hamaspyur” (campion) are described, a plant worshipped in certain regions of ancient Armenia and dedicated to the goddess Astghik. In the same source, it is stated that Shirakatsi found that very rare plant in Dzoghakert in the province of Ayrarat and used it for medicinal purposes.

The age-old struggle of the Armenian people against Arab rule ended with the restoration of the Armenian state. This in its turn, restored Armenian economy, brought about an increase in towns and a flourishing of crafts, trade and culture which is characteristic for the epoch of Armenian Renaissance (10-14th centuries). Especially favourable conditions for the development of art, science and medicine in particular, were created in the 10-11th centuries, during the rule of the Bagratuni family in Ani. Schools of higher education or medieval universities were founded in Ani, Haghpat and Sanahin, where along with philosophy and the natural sciences, medicine was also a subject of study.

Many Armenian philosophers displayed great interst in natural sciences, especially Hovhannes Sarkavag (1045-1129) who lectured at the Ani and Haghpat schools of higher education. Sarkavag, expressing the tendencies of the epoch of Armenian Renaissance, advocated the separation of science from religion and the necessity for the experimental study of nature. “The researcher must not only have an all-around education and knowledge, he must not only know the Bible but also the secular sciences. If he completely masters all this, just the same, he cannot be convinced of it without experiment. It is only experiment that makes facts firm and irrefutable”. These ideas of Armenian philosopher preceded those of the representatives of the European Renaissance and especially the well-known thesis of Roger Bacon (1214-1292).

The medical conceptions of Armenian Renaissance are reflected rather completely in the works of Grigor Magistros (980-1037), a contemporary of Ibn Sina. A scholar, well-acquainted with ancient culture in all its various aspects and being an erudite, Grigor Magistros Pahlavuni displayed his abilities in different branches of Armenian culture – as a poet, a philosopher and a physician. Very often he was forced to interrupt his scientific studies under the quiet, calm arches of the monastery libraries and universities, and put down his pen to take up arms. During the tempestuous years of the last Bagratunis, Grigor Magistros, like his uncle, the sparapet (supreme military leader) Vahram Pahlavuni, took up arms to protect his country against numerous enemies. When the battle cries were silenced and years of peace followed, he again devoted himself to scientific work and to restoring and rebuilding the monasteries destroyed in the different regions of Armenia (Sanahin, Taron, Kecharis, Havuts Tar).He had close ties with scientists and statesmen of Armenia and Byzantine as well.

The capital of the Bagratuni, which at that time had a population of more than 100,000 and was a large trade centre, attracted scientists from different countries of the world. Grigor Magistros kept in touch with many of them by correspondence. Those “Letters”, of which very fortunately part has survived, give a picture of the life and customs of the time, the culture at the Armenian capital – in other words, the wide sphere of Magistros’ interests as physician and philosopher. One of his letters was addressed to Kyriacos, the Byzantine physician. who lectured at Ani on the physiology of the digestive organs. During the discussion, the Greek physician, replying to a question given by Grigor Magistros, said that nothing whatsoever interested him, outside his narrow sphere. In his brilliant letter of reply, a wonderful example of the epistolary art, Magistros exposed such a one-sided approach and, in the light of ancient natural philosophy, he explained the close affinity existing among natural phenomena. In this scientific dispute with Kyriacos, which lasted a number of years, Magistros revealed his profound knowledge of medicine and the works of Plato, Hippocrates, Galen, Asclepiades, Nemesius of Emesa, whose successor he considered himself.

Grigor Magistros was not only fascinated by theoretical questions on medicine, he was also a skilled practical physician. In his letter to the abbot of Sevan monastery, he wrote about the disease of Gagik, the last king of the Bagratuni dynasty. In other letters he described small pox with which his own son had been infected or gave sensible instructions to Sarkis vardapet who suffered from liver illness. Thus we see in Grigor Magistros an experienced physician with fine professional sensitivity, well-versed in clinical medicine and especially in phytotherapy. He advised one of his correspondents who was suffering from liver disease, to use lettuce seeds. “If the shell of the seed is white, it brings about weakness which induces sleep. Often, if it is put on the wound, it has a soothing effect on the patient who has fever. If its seed is mixed with saffron and put on the patient’s forhead, it reduces the inflammation of the burning wound. There are many other sorts of lettuce which we believe are helpful not only to patients suffering from fever”.

Such an intellectual atmosphere promoted the development of the secular sciences and, of course, medicine. It was in Ani, during the peak of the Bagratuni rule that original studies on problems of pathology, therapy and pharmacology, so-called bzheshkaran’s (medical books) first appeared. Unfortunately time has not preserved for us the author’s name of the famous “Bzheshkaran”, which was written during the rule of “the victorious King Gagik”(this refers to King Gagik I (990-1020) of the Ani Bagratuni dynasty), in other words, at about the same time as when Ibn Sina created his “Canon”. Later it was edited in Cilician Armenia and was called the “Gagik-Hetumian Bzheshkaran”.Vahram Torgomian, the honoured historian of Armenian medicine, believed that the author of medical book of Ani was Grigor Magistros, while the Cilician materials in “Gagik-Hetumian Bzheshkaran” belonged to “Mekhitar the Great”. [Fig.4]

It is not at all accidental that the above-mentioned “Bzheshkaran” was edited in Cilician Armenia and was enriched with two additional sections. After the fall of the Bagratunis (in 1045) the Rubenid Cilician state became one of the political and cultural centres in medieval Armenia. Later, in 1198, it set up the Rubenid kingdom, where Armenian intellectuals – poets, musicians, painters, scientists and physicians gradually gathered. In Hromkla, in the patriarchal chambers of Catholicos Nerses Shnorhali (1166-1173) and Grigor Tgha (1173-1193) and in Sis, the capital of the Rubenid and Hetumid kings, favourable conditions were set up for the development of the natural sciences and medicine in the spirit of the traditions of Armenian Renaissance.[Fig.5]

The fruitful scientific and medical activities of Mekhitar Heratsi were connected with Cilician Armenia and the medical school there. He was called “Mekhitar the Great” by his contemporaries and by physicians of later periods. He was the founder of medieval Armenian medicine. He played the same role in Armenian medicine as Hippocrates did for Greek, Galen for Roman and Ibn Sina for Arab medicine. He gathered, studied and deduced from the experience of the past in classical as well as folk medicine, creating such works as have not lost their value even today. The necessary preparatory work was done by unknown Armenian physicians, the precursors of Mekhitar Heratsi, who translated the scientific heritage of Greek, Roman and Arab physicians and also created a number of works of their own, mainly on pharmacology and therapy. But all that was not enough for such a serious, demanding scientist as “Mekhitar the Great”. This is how he characterized the existing conditions in Armenian medicine at that time, in the preface to his work “Consolation of Fevers”: “I, Mekhitar Heratsi, insignificant among physicians, have been since childhood, a follower of wisdom and the art of medicine and having studied the Arabic, the Persian and the Greek Science, saw, by reading their books, that they mastered the perfect art of medicine, according to the first sages – philosophers, that is, the prognostic, the essence of medicine; while among Armenians, I did not find the like, but only about treatment”.

Leaving his native town of Her (present day Khoy in Perssia) in the first half of the 12th century, the young Mekhitar departed for Cilician Armenia, where he received a medical education and the honorary title of “bzheshkapet”(doctor of medicine). Being a man of unusual energy, a peaceful life with a definitely-patterned routine was not for him. By character a man fond of experiment and research, he often travelled to distant lands in search of medicinal herbs thus leading the adventurous life of a periodeuta (travelling physician). After that a new period in his life began when he experimented on the pharmacological properties of drugs, at patient’s bedside, the results of which are summarized in his works. It was during that period that he wrote his studies on the anatomy of man, biology, pathology and pharmacology. The great part of these works, unfortunately, because of the tragic fate of the Armenian people, are lost forever. Only individual fragments are to be found in collections in the manuscripts of later physicians.[Fig.6]

That Mekhitar Heratsi was a physician and a natural-scientific researcher with broad interests may be seen from even those short extracts entitled “On the Structure and Origin of the Eye”, “On Hernia”, “On Precious Stones”, “Predictions of Storms and Earthquakes”. As far as his works on pharmacology and pathology are concerned, they too were long thought to be lost. However, later specialists in the history of Armenian medicine believed that they were also included in the “Gagik-Hetumian Bzheshkaran” together with the work “Consolation of Fevers”. [Fig.7]

As a result of such rich, prolific work in science and medicine, the Armenian “bzheshkapet” had, by the 60’s of that century, attained great fame in medicine. He was a close friend of Catholicos Nerses Shnorhali who dedicated to him one of his natural-philosophic poems entitled “On the Heavens and its Stars”. In the 80’s of the 12th century, Mekhitar Heratsi began the main work of his lifetime, the “Consolation of Fevers”, for which he perseveringly gathered material over a long period of time.He was not only reading the works of ancient physicians and the Arabs also, but roaming over the marsh-ridden valleys of Cilician Armenia and studying malaria widespread in those places, and other contagious diseases.

It was not at all surprising, therefore, that that work was the centre of attention of all those concerned with the welfare of the people. First and foremost among them was the philosopher and poet Grigor Tgha, the Armenian Catholicos, who encouraged and aided the “bzheshkapet” in all aspects of his work. In the preface to “Consolation of Fevers” Mekhitar Heratsi wrote: “I wanted to write this book briefly, within the best of my ablities, on only three kinds of fevers with prognostic and therapy… I enjoyed the love and patronage of Grigor (Tgha) supreme Catholicos of Armenians, who was responsible for my writing this work…That was why I agreed to write this book, for the sake of necessity and usefulness… We wrote this book, calling it “Consolation of Fevers”, so that it would console the physician with knowledge and the patient with good health”. Convinced that his book would be helpful not only to specialists but for the people too, Mekhitar Heratsi wrote it not in “grabar”(ancient Armenian) which was the scientific language of that time, but in middle Armenian, the vernacular of Cilician Armenia. His daring step is evidence of the democratic nature of the great “bzheshkapet’s” outlook which left its deep impact on later development in Armenian medicine. Mekhitar Heratsi devoted much effort to creating medical terminology in Armenia. He followed the right path, using basically Armenian words. Numerous terms which he created at that time, have been preserved and are in use in modern medical literature today.

The “Consolation of Fevers” reflects the world-outlook of Mekhitar Heratsi as a great scientist, his spontaneous materialistic approach to the essence of fever-causing factors. This resulted in his unique, so-called theory of “mouldiness ” which explained also the origin of tumours. Besides the external aetiological factors, well-known to ancient and Arabic authors (Hippocrates, Galen, Ibn Sina), for the first time in medicine he suggested a new idea of “mould” as a living factor. Levon Hovhannissian, a prominent scholar in the history of Armenian medicine, wrote: “It is an irrefutable, objective fact that up to the premicrobiological period, no physician ever used such a term to describe the essence of infection, one so close to the truth, as did Mekhitar Heratsi”. Heratsi classified fevers into “one-day”, “mouldy” and “wasting”(consumptive) fevers. In this case however, our “bzheshkapet” was guided by intuition when he separated one-day fevers, which do not fit within the limits of humoral pathology. To explain their pathogenesis he referred to the pneumatic theory of ancient authors. Here however, the main point is that the experienced physician did not overlook some “unusual” features of the course of the disease. This serves as a basis for us to suppose that in the one-day fever group, he described a few kinds of allergies (physical, chemical, neuropsychical).

In the “mouldy” fever group Mekhitar Heratsi included a number of contagious diseases widespread in the Middle Ages as, for example, malaria, typhoid fever and septic diseases, the plague, small-pox, measles. The extensive experience of the great bzheshkapet enabled him to clarify the mouldy nature of fever, especially the highly contagiousness of typhoid fever.”If the patient suffers much from high temperature and moves uncomfortably from side to side, if his belly swells and if at a percussion, a tympanic sound is heard, you may be sure that he will die, especially if there are black dots on his body as large as sumac. People should stay away from him and not come in contact with him”, he wrote in his “Consolation of Fevers”. It was later, in the 16th century, that in European science the famous Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro developed these ideas in his work “On Infection, Infectious Diseases and their Treatment”(1546).

As for the wasting (consumptive) fevers which correspond to the different clinical forms of tuberculosis in Mekhitar Heratsi’s opinion, they are brought about by emotional disturbances, over-exhaustion, malnutrition, unfavorable climatic conditions – factors which even today, medicine considers of great significance in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis.

In describing symptoms and the course of fevers, Mekhitar Heratsi comes to light as a serous, wise physician who mastered the different methods of examining the patient beginning with a detailed anamnesis with the patient to the objective methods used in medicine even today as examination, palpation, percussion, auscultation. Heratsi placed great importance on taking the patient’s pulse, determining the temperature as well as an analysis of the mucous, urine and other discharges. He approached the disease from a dialectic point of view, dividing it into four stages. Applying the Hippocratic theory, he advised physicians to have an individual approach to each patient, taking into consideration the course of the disease and its stages and accordingly foretell its outcome.

Armed with such knowledge, Heratsi used the experimental approach, often contrary to the scholastic point of view, and developed a complex system of cure based on the use of medicaments, especially herbs, as well as dietetic and physical methods. Faithful to the ancient principles of medicine, the Armenian “bzheshkapet” suggested conducting the treatment according to Hippocrates, that is curing “opposites by opposites”. Mekhitar Heratsi considered phytotherapy the most important, based on Armenian folk medicine as well as on the experience of ancient and eastern medicine.

In treating contagious-allergic diseases, the most useful among the medicaments suggested by the Armenian “bzheshkapet” were the herbs with antibacterial, antiinflammatory and antiallergic properties. The following herbs are used in complex prescriptions in the “Consolation of Fevers”: water-lily, violet, iris mullein, hyssop, inula, mugwort, plantain, liquorice plant, meadow saffron, caper bush, mint, caltrops , thyme and many others. Besides herbs, drugs of animal origin (castoreum, ox bile) may be found in those prescriptions as well as mineral preparations (Armenian clay, sulphur, zinc, boric etc.). They are endowed with tonus-raising, antisclerotic, antitoxic. hormonic and many other still scantly explored medicinal properties.[Fig.8]

Mekhitar Heratsi suggested special diets for patients suffering from fever, which included mainly greens, vegetables and fruit, fresh as well as dried, juices and sweets prepared from them. Patients were advised to use coriander, basil, celery, okra, purslane and such fruit as pomgranate, quince, grapes, oleaster, figs, jujube plums. The Armenian “bzheshkapet” advised giving the patient easily-digestible food as fresh fish, chicken, meat broth, egg yolk, milk (for tubercular patients goat and donkey milk was recommended).

Among physical methods of treatment, Heratsi considered water therapy (shower, baths) as well as cold spongings and gymnastic exercises very important. Armenian bzheshkapet also attached great importance to psychotherapeutic methods, suggestion, using music for that purpose. Thus during “one-day” fever which, in his words, come about from “worries and bitter cares”, he recommended the following.”Amuse (the patient) with games and jokes and in every way possible, make him gay. The patient should listen to the songs of gusans (minstrels) as much as he can, to the sounds of strings and delightful melodies”.

The oldest copy of “Consolation of Fevers”, written in 1279 may be found today in the Mashtots Matenadaran (codex 416). The study of this work reveals the high level of Armenian medicine during the time of Mekhitar Heratsi. All this truly places the Armenian “bzheshkapet” among the first ranks of medieval physicians. In 1908 Ernest Seidel who translated the “Consolation of Fevers” so brillantly into German, had the following to say about the Armenian physician:”For example, when we, without prejudice, compare Hildegard’s “Physics” which was written a few decades before, with that of the Armenian master, we are compelled to definitely grant the laurel of the first place to Heratsi for having basically known nature, for his consistent and individual thinking and for being completely free of the yoke of scholasticism”.

Grigoris (13th c.) was also a physician of the Cilician school, whose “Analysis of the Nature of Man and his Ailments”(Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 415) gives a picture of the development of pathology and clinical medicine in Cilician Armenia. The detailed clinical data in Grigoris’ book is evidence of the fact that in Cilician Armenia, hospitals were developing, where physicians could follow the course of the disease directly at the patient’s bedside and not be satisfied with only information gathered from books. Thus, on evidence given by Armenian historians, hospitals, homes for lepers and other such homes were set up in Cilicia during the rule of the Rubenids. In that respect very much was accomplished by King Levon II (1185-1219), his daughter Queen Zabel (1222-1252), King Levon III (1270-1289) and other representatives of the Rubenid and Hetumid dynasty.

As for a etiology, Grigoris was Heratsi’s follower applying the theory of “mouldiness” not only to “mould fevers” but also to wasting (consumptive) fevers, extending it over various diseases of the lungs, heart, liver and stomach. Like Mekhtar Heratsi, Grigoris too, studied the contagiousness of fevers, especially that of tuberculosis and leprosy. With reference to tuberculosis, he wrote the following:”Those between 18-35 years of age become ill with tuberculosis because at that age man’s nature are mild, and if the pus becomes mouldy, it contaminates his lungs very quickly… Wise physicians say that those who become infected with that disease are those who come in contact with the patient especially in summertime and if the room is rather small. Infection may also be inherited from the parents”. Thus, in giving a picture of lung tuberculosis, he mentioned the “pulmanic noduli”, “ulcers” and “calculi” which the modern pathologist interprets as tuberculous infiltrates, cavern and the focus of calcination. Grigoris developed another of Heratsi’s thesis on the need to study the anatomical structure of the sick organism, thus becoming the forerunner of pathologic anatomy in medieval Armenian medicine.

The medical activities of the Armenian physician Aharon of Edessa and his family (in 12-14th centuries) were closely connected with the Cilician school. Stepanos, the son of Aharon, created a valuable medical book entitled “Dsaghik”(“Flower” or more exactly, “Anthology”) in 1232. In the preface of the book Stepanos wrote, “I, Stepanos, the son of physician Aharon of the Edessa, also called Urfa, God’s humble servant, composed what has been considered helpful by the study of many, and which I have studied from such physicians as my father, and the Great Mekhitar and Simon”. Stepanos’ work, which summarizes data on clinical medicine and pharmacology was barbarically destroyed, along with numerous other Armenian manuscripts , in Turkey during World War I and the Armenian massacres.[Fig.9]

The activities of the Syrian physicians Abusaid, Ishokh, Faradj in Cilician Armenia during the 12-13th centuries is of great interest. The scientific ties between Armenian and Syrian physicians, about which there is evidence from the end of the 10th century in medical books of Ani, were particularly strenghtened in Cilician period. They all lived in an Armenian environmert, wrote in middle Armenian and were in close friendly relations with prominent figures in Armenian culture, Nerses Shnrhali and Nerses Lambronatsi (1153-1198). [Fig.10]

Such works as “On the Structure of Man”(12th c.) by Abusaid, “Book on Nature”(13th c.) by Ishokh, “Bzheshkaran on Horses and Other Beasts of Burden”(1296-98) by Faradj and other medical and biological treatises were very popular in medieval Armenian literature. There are many copies of these works in the Mashtots Matenadaran (codices 549, 715, 4268, 10975 etc.), a precious relic of the treasury of Cilician Armenian medicine.[Fig.11]

During the 13-14th centuries, there was a noticeable increase in activities in the schools of higher education in historical Armenia. The foundation of natural sciences and medicine were taught in Yerznka, Gladzor and Tatev, large scientific centres with ancient traditions. It was during that period that in the schools of higher education of Krna and Dsordsor, centres of unitarism, that the works of a number of eminent scientists of medieval Europe were translated from Latin to Armenian. Among them were those of Albertus Magnus (1193-1280) the famous philosopher, botanist, zoologist and physician, and also the theological and natural philosophical works of Thomas Aquinas. Thus, although the ideological-political thesis of the Armenian unitarians was firmly opposed by famous figures in the schools of higher education in Greater Armenia, first and foremost those of the Gladzor and Tatev schools it did not prevent them at all from studying and spreading such works as those of the Armenian unitarians with the cooperation of European scientists.[Fig.12]

Of the medieval Armenian schools of higher education, the Tatev school is worthy of special mention, where the greatest thinker of that time Grigor Tatevatsi (1346-1409) was active. In his works, besides the basic problems of philosophy, those of the natural sciences and medicine were also studied. Grigor Tatevatsi’s “Book of Questions” is an extensive treatise written in 1389, where the author’s ideas on human anatomy, biology, psychology and embriology were expressed. In the “Book of Questions” the tenets of physiognomy were critically examined. These questions also interested Albertus Magnus in his “Compedium Theologicae Veritatis”. In answering the question – “Are external features true? Do they really express man’s character?” – Tatevatsi wrote:”We can say that they are not true for the following five reasons: firstly, such features are not compulsory for man, they show that nature has specific tendencies; secondly, since they are not large or small and are sometimes even similar for all men; thirdly, since they can be suppressed when desired, by the intellect; in the fourth case, those features are often accidental and not at all natural; and fifth, since man can, contrary to his habits and by means of abstinence, prayer or control over his body, suppress himself and not manifest those qualities. It can be deduced from all this that we must not think badly of a person, if such features are noticed on him”.

The downfall of the kingdom in Cilician Armenia at the end of the 14th century and the continual wars in the 15-16th centuries between Ottoman Turkey and Persia, for rule over the territory of historical Armenia, brought about a decline in Armenian culture. During those bitter difficult years, the classical traditions of Armenian Renaissance in medicine were preserved in only a few cultural centres, the last brilliant spark of which was the works of the prominent physician Amirdovlat Amasiatsi in 15th century. He was the successor of Cilician medical school, who developed the work of the previous period, with which, in his own words “were involved our first physicians – the Great Mekhitar, physician Aharon, his son Stepanos and their family and the physicians Djoshlin, Sargis, Deghin, Simavon, Vahram, who have written many books on the influence and usefulness of medicine”.[Fig.13]

The Armenian “bzheshkapet” was born in the town of Amasia in Asia Minor, which had a large Armenian population, many Armenian schools and churches. Although the exact date of his birth is not known, yet scholars in the history of Armenian medicine, based on certain indirect facts, believe it to be in the first quarter of the 15th century. That was politically an extremely tempestuous period, when the western provinces of Armenia fell under Ottoman-Turkish rule. Amirdovlat Amasiatsi lived at the time and was probably even an eye witness of the capture of Constantinople in 1453 by Mohammed II, since in the 50’s of the 15th century Amirdovlat had departed from his native town and resided in this famous cultural centre, where he very likely studied medicine under skilled physicians. Here Amirdovlat soon won acclaim as a physician, and was invited to Sultan Mohammed II’s palace as his personal physician, receiving the honorary title of “djarapasha ramatanin” which literally means “head surgeon-oculist”.[Fig.14]

By that time, Amirdovlat Amasiatsi was an experienced, mature physician with great knowledge, when in 1459 he wrote his first work in Constantinople “on the request of Shady-bek’s son, Vard”. This book was entitled “Teaching on Medicine”, in which problems of embriology, anatomy, physiology, pharmacology, pathology and hygiene are presented in the spirit of the ancient and Arab medicine. In the “Teaching on Medicine” by Amirdovlat Amasiatsi, the author’s tendency to reexamine the age-old experience of Armenian folk medicine in pharmacology can also be felt, for which our “bzheshkapet” revealed deep interest all through his creative life. A brilliant expression of that was his first “Akhrapatin” written in the same year 1459. In that work he tried to compile a dictionary of “simple” and “complex” drugs, of which, some quarter of a century later, he created his two voluminous works, the second”Akhrapatin” and “Useless for the Ignorants”. The autograph of these works may be found today in the Mashtots Matenadaran (codex 8871).[Fig. 15]

As for the “Teaching on Medicine”, it was later completely rewritten by the author and enriched with new chapters on pathology and clinical medicine. The clinical section of that work demanded quite a lot of time, since Amirdovlat’s next book, enitled “The Usefulness of Medicine” was completed in 1469 in the town of Philippopolis (present-day Plovdiv, Bulgaria). In this work the author’s point of view on all the fundamental problems of medicine is expressed. It is amazing in revealing the “bzheshkapet”s broad scientific outlook and his profound knowledge of previous medical literature.”The Usefulness of Medicine” is written on the level of the best works of the time and summarizes the knowledge of medieval Armenian physicians on theoretical and practical questions. The section on clinical medicine is of particular value. Descriptions of more than 200 diseases of the internal organs as the brain, nerves, senses, heart, respiratory organs, the liver, stomach, intestines, urogenital and other systems as well as fevers, malignant and non-malignant tumours, poisoning, etc. were given with methods of medicinal and dietary treating.

The decade of his lifetime when these valuable works were created, was at the same time full of dramatic events in his personal life. On the one hand, he gained more and more fame as a humanist physician and talented scientist, while on the other hand, as a Christian, he felt the jealousy and open hatred of his enemies, who were not few in the Mohammedan ruled palace. In the preface to “The Usefulness of Medicine” Amirdovlat wrote, “I have suffered many difficulties and hardships at the hands of infidels and foreigners, judges, kings and princes. For many long years I have been in exile. I have seen good and evil, I have met with adversities, I have known riches and poverty. I have wandered from land to land and practised my medicine, have used drugs according to my knowledge. I have served the sick – noblemen and rulers, military men of different ranks, citizens and paupers, the aged and the young”. Forced to leave the capital, Amirdovlat did not let the ten years of exile pass in vain. Continuing his humane duties towards sick people, be they rich or poor, Amirdovlat studied the medicinal herbs of the land where his fate as a physician-periodeuta took him, often making experimental studies in the field of pharmacology.

In the 70’s Amirdovlat returned from exile to Constantinople and judging from data in manuscripts, again received the honorary position of personal physician to the sultan. It was during those years that the great “bzheshkapet”‘s love for Armenian literature manifested itself, his love for the creations of the physicians and philosophers of the ancient world. In the colophon of a collection (Mashtots Matenadaran codex 1921) which contains Aristotle’s philosophical works with Grigor Tatevatsi’s Commentaries, Andreas the scribe tells us that the manuscript was copied in 1492 in Amasia at the desire and with the agreement of physician Amirdovlat “who as a bibliophile, is at present, the second Ptolemy”.

After the death of Mohammed Fatih (1481) Armenian bzheshkapet came back home. In the colophon of the book “Useless for the Ignorants” which is today in the British Museum (codex Or. 3712 ) the scribe mentioned the exact date of Amirdovlat’s death:”The physician Amirdovlat, the author of this book, passed away true to the Christian faith, in 1496, on Thursday December 8″.

During the later period of his life, he created his most outstanding works on pharmacology – the second “Akhrapatin”(1481) and the “Useless for the Ignorants”(1482).[Fig.16]

A little before those works, Amirdovlat wrote “Folk Book”(1474) which gives the basis for calling him astronomer, as Mekhitar Heratsi was called, in the medieval meaning of the word, when frequently the concepts of astronomy and astrology were closely knit.

A study of Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s works shows that although he was occupied with practical surgery, especially ophthalmology, yet taken as a whole, he preferred conservative methods of treatment (especially phytotherapy and nutrition). It must be mentioned that the Armenian bzheshkapet was particularly interested in pharmacology where he summarized the age-old experience of folk and classical medicine.

Amirdovlat’s “Uselesss for the Ignorants” is an encyclopedia of medieval Armenian pharmacology with the names of medicaments given in five languages: Armenian, Greek, Latin, Arabic and Persian. It contains 3500 names and synonyms of more than 1000 medicinal plants, 250 animals and 150 minerals. A study of that work by modern physicians makes it possible to become acquainted with the medicaments of Armenian medicine in the Middle Ages, and first of all with phytotherapy which was its main field. To cure all those diseases, in the cause of which, based on data today, the contagious-allergic factor plays a definite role, Amirdovlat Amasiatsi used such herbs as cowparsnip, inula, camomile, mugwort, hyssop, thyme, sweet-flag, black cumin, caltrops, pearl-plant, all native to Armenian plant life. Alll these herbs were rich in ether oils, vitamins, plant hormones and other substances which made for their curative influence. By means of the same experimental methods, the Armenian bzheshkapet revealed the antitumoural properties of hog’s fennel, field eryngo, red periwinkle, heliotrope, meadow saffron and certain other plants. According to present data, they contain coumarin and furocoumarin derivatives as well as the alcaloids colchicine and vinblastin which have antitumoral influence. Amirdovlat attached great significance to those herbs which had antitoxic (lavender, marigold, ironwort) and tonus-raising properties (birth-wort, snake bryony).

The most of above-mentioned plants Amirdovlat used to prevent premature ageing and to maintain good health and vitality. For the same purpose he used some gums of plant, animal and inorganic origin (galbanum, sagapenum, assa-foetida, propolis, mumia etc.) [Fig.17]

Mumia, a complex natural compound formed from plant residues, excretions of animals and products of the destruction of hydrocarbons in caves of numerous countries (Iran, Afghanistan, Middle Asia) was recommended by Amirdovlat to raise the tonus of the body, to heal wounds and treat tumours. There is information on the extraction of mumia in Armenia in “Useless for the Ignorants”. The author said, “There are ten nearby caves with ten different names where the mumia is produced”. Altough he did not give the names of those caves, recent findings of mumia on the territory of modern Armenia (in caves of Eghegnazor) verify the data of the medieval Armenian bzheshkapet.

To use this vast amount of medicaments in Armenian pharmacopeias freely and correctly, not only need the physician to have had great experience and deep knowledge, but also be well aquainted with botany, zoology and chemistry. Amirdovlat Amasiatsi was endowed with all these qualities harmoniously combined. He made his significant contribution to medieval medicine, creating a whole library of medical works, written in middle Armenian, accessible to the people.

Thus the Armenian bzheshkapet’s long life was replete with medical courage and devotion, with study and the search for new medicaments, collecting and preserving manuscripts and composing new books. Amirdovlat’s works are imbued with a deep consciousness of the physician’s duty, with high ethical standarts. He often expressed the principles of medical ethics,”The physician must be endowed with intellect and a sense of duty. Under no circumstances may he be fond of drinking, greedy and self-interested. He must like the poor, be merciful, devoted, pious and morally clean. If he cannot understand the essence of the disease, he must not give the patient medicine to not bring shame on himself. If he is ignorant, then it is better not to have him visit the patient and generally speaking, he must not be considered a physician”. Many of these principles had been formulated by Hippocrates, the father of ancient medicine.

Like all great physicians, Amirdovlat was not alone in practising his art. He created a school of Armenian phytotherapeutists, which existed for a few centuries and the traces of whose influence can be noted in the works of such representatives of the Sebastian medical school as Hovasap, Asar and Buniat Sebastatsi. The works of Amirdovlat Amasiatsi in which as in Ibn Sina’a “Canon”, almost all important branches of medicine are presented (embriology, anatomy, physiology, clinical medicine, pharmacology, surgery and therapy) have served for centuries as a medical encyclopedia. Their many hand-written manuscript copies scattered all over the world is proof of the great interest which medieval Armenian physicians took in Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s works.

During the 16-17th centuries Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s traditions have been developed by the physicians of the Sebastian medical school, who besides creating their own works, paid great attention to editing and interpreting Amirdovlat’s and other authors’ books. Thus, in 1614, Asar Sebastatsi wrote and in 1622 edited “The Book on the Art of Medicine”, to which is added a medical dictionary in five languages. This book is of special interest because it makes extensive quotation from the works of Mekhitar Heratsi and other Armenian physicians, works lost to mankind. When editing Abusaid’s “Anatomy of Man” in 1625, Asar Sebastatsi included therein a part “On the Structure and Origin of the Eye” from the Heratsi’s work on ophthalmology, which is now lost too.

Similarly prolific were the activities of another representative of the Sebastian school Buniat Sebastatsi. In 1626 in the town of Marzvan he edited Amirdovlat’s book “The Usefulness of Medicine”, the Matenadaran copy of which (codex 414) served as the basis for its comparative-critical text published in 1940 by Stepan Malkhasiantz. It was in the spirit of this book that in 1630 Buniat Sebastatsi summarized his medical experience and in the town of Samsun, wrote “Book on Medicine”. Like Amirdovlat he collected and studied for his work the various sources of Armenian and foreign authors. In 1632 Buniat Sebastatsi edited Amirdovlat’s book “Useless fot the Ignorants”. Its comparative-critical text was published in 1926 by K. Basmadjian.

With the physicians of the Sebastian school ends the last period in the development of medieval Armenian medicine. Although up to the first half of the 18th century and even later, certain authors wrote their works along the traditions of Amirdovlat Amasiatsi and Mekhitar Heratsi, yet these last Mohicans in medieval Armenian medicine could not withstand the pressure of modern medicine.

Beginning with the second half of the 18th century, a number of Armenian physicians came to the fore, who had received their education in European and Russian institutions. Among them must be mentioned Petros Kalantarian, Stepanos Shahrimanian, Hovakim Oghullukhian, Mikael Resten. Petros Kalantarian was born in 1735 in Nor Djugha, then moved to Russia, graduated from the Petersburg Hospital School (later Military Medical Academia). His medical and scientific activities were closely connected with Moscow. In the preface to his “Bzheshkaran”, published in 1793 in Nakhidjevan on the Don , he requested that “the modest physician Petros Djughayetsi be remembered, the son of Hovhannes Kalantarian, who now lives in Moscow, the capital of Russia”. His book was devoted to the treatment of a number of contagious, allergic, skin and nervous diseases. Besides the medicaments used in European medicine Petros Kalantarian also suggested a whole series of remedies widely used in medieval Armenian medicine. Petros Kalantarian’s “Bzheshkaran” also has a list of medical terms at the end where the names of the medicaments are given in Latin and Armenian as well as Greek, Arabic, Persian and Russian.

Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s traditions left a deep impression on the works of another famous Armenian physician and botanist Stepanos Shahrimanian (1766-1830). Though he received his education in Europe, graduating from the medical faculty of famous University of Padua, he conducted his medical practice mainly in the Caucasus and Tiflis after a short period of life in Constantinople. In 1794-1818 he wrote in Tiflis his extensive work “Botany or Armenian Flora” which unfortunately is as yet, unpublished. The manuscript copies of that work, preserved in the Mashtots Matenadaran (codices 6267, 9856 etc.) give us an idea of the detailed, painstaking effort which he spent on his book, for almost a quarter of a century. In that book, those Armenian medicinal herbs are described, which were used extensively in medieval phytotherapy and especially in the “Useless for Ignorants” by Amirdovlat Amasiatsi. [Fig.18]

Stepanos Shahrimanian was also the author of a work on the medical treatment of the plague, which he wrote in 1796 in Constantinople where an epidemic of the plague was raging at that time. It must be mentioned that Armenian physicians beginning with Mekhitar Heratsi, have always been most interested in both the plague and other contagious diseases, their etio-pathology and treatment. Along with other medicaments suggested by Stepanos Shahrimanian was the Armenian clay, one of the most favourite remedies in Armenian folk medicine. It is clearly evident from Shahrimanian’s works that he was well acquainted with modern European medicine and with Carolus Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) classification of plants and new achievments in botany.

In the second half of the 19th century, a whole constellation of talented physicians came to the fore: Margar Arustamian (1854-1901), Vahan Ardzruni (1857-1947), Harutiun Mirza-Avagian (1879-1938), Levon Hovhannissian (1885-1970) and many others who were innovaters in old Armenian medicine and founders of the new. The vast experience of Armenian folk and classical medicine in the field of phytotherapy attracted the attention of and was studied by such great specialists in medicinal botany and pharmacology as Hovhannes Sepetjian, Simon Mirzoyan, Sofia Zolotnitskaya and others, forming an endless source for pharmaceutical production of Armenia. Modern medicine today very often refers to the rich treasury of ancient Armenian medicaments in treating a number of diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis, physical disturbances and allergies – problems, which have not yet been solved today.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. A fragment of “Materia medica” by Dioscorides ( Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 141, 6-7th c.)

2. White bryony – Bryonia alba L. and black bryony – Tamus communis L. (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 6594, end of 17th c.)

3. The first page of “Galen’s Dictionary”(Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 266, 1468, Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s autograph)

4. The physicians examinig the patient (Jerusalem, Armenian Patriarchate, codex 370, 12th c.)

5. Nerses Shnorhali and Mekhitar Heratsi (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 7046, 1644)

6. An anatomical picture of optic nerves with chiasma opticum (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 8871, 1459, Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s autograph )

7. The title-page of Mekhitar Heratsi’s “Consolation of Fevers”(Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 416, 1279)

8. Medicinal herbs used in medieval Armenian phytotherapy – Phalaris tuberosa L. and Mentha L.(Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 6594, end of the 17th c.)

9. An anatomical picture of man (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 414, 1626)

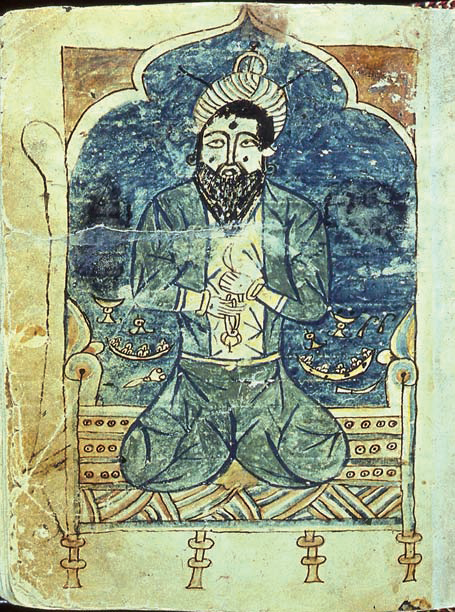

10. A portrait of philosopher and physician Djnay (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 10975, 1296-1298)

11. An anatomical picture of a horse with commentaries (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 10975, 1296-1298)

12. Grigor Tatevatsi with his disciples (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 1203,1449)

13. The medieval Armenian physician (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 8382, 14th c.)

14. The physician-oculist and his patient (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 8382, 14th c.)

15. The title-page of Amirdovlat Amasiatsi’s “Teaching on Medicine”(Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 8871, 1459, autograph)

16. The “Useless for Ignorants” by Amirdovlat Amasiatsi (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 414, 1626)

17. Species of Opopanax Koch. used in medieval Armenian phytotherapy (Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran, codex 6594, end of the 17th c.)

18. The title-page of the Stepanos Shahrimanian’s “Botany or Armenian Flora”(Yerevan, Mashtots Matenadaran. codex 6267,1818, autograph)

source: www.armenian-history.com